Portland’s Abyssinian Meeting House is the third oldest African American meeting house in the United States. It was the first of two sites in Maine to be recognized by the National Park Service as part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. (The other is the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Brunswick.) In 2006, the meeting house was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and the nonprofit that owns it is slowly progressing on a long and complicated path of historic restoration. It has a long, long way to go, but this is a most worthy project.

Built in 1828 by free blacks, the building, which once served as a church, school and community center, is in need of complete renovations inside and siding outside. On First Friday, however, the building thundered with the sound of drums and people. More performances and gatherings are scheduled and art fills the street-level basement. Within the fascinating narrative of the building, it might be easy to underestimate the accomplishment, scope and scale of the participating group of artists. Just between lead organizer Daniel Minter, Ashley Bryan and David Driskell, the participating Maine-based African American artists have published many dozens of books and have won scores of national and international awards and honors. While you would be hard-pressed to find a more accomplished and renowned group of Maine artists, the real story here is the art.

Driskell and Bryan are represented by only one work each. And yet this feels right. Both are internationally acclaimed. Driskell just had a show at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art and Bryan was recognized with a 2017 Caldecott Honor.

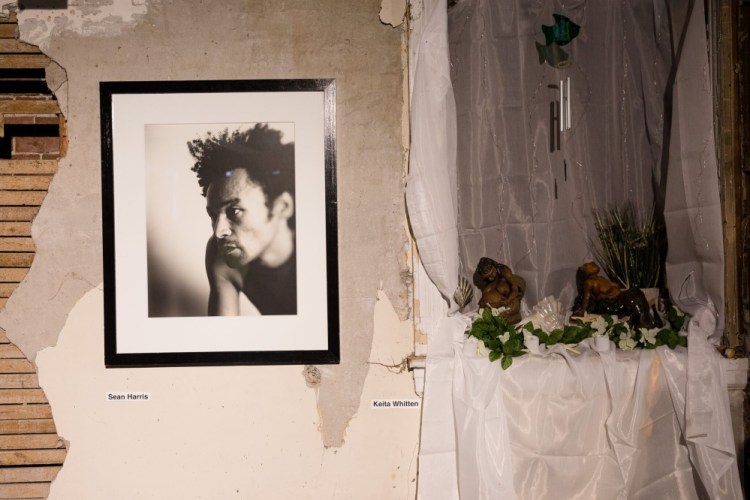

Bryan and Driskell might be the biggest names, but they are joined by a strong group of artists. Sean Alonzo Harris’ handsome portrait of Anthony “Chan” Spotten recalls a Portland dancer and artist who moved to New York and who died in 2005 of AIDS. Titi de Baccarat’s painting-like installation works leap into space like players on a stage, but rather than fictional theatricality, the energy is ritualized, totemic and present. Clyde Bango’s wire wall pieces meander between description, decoration and dance. Elizabeth Jabar’s portrait of a nomadic woman offers a seamlessly respectful touch of elegant feminism at the nexus of Middle Eastern, African, Western and Maine cultures. (Jabar hails from Waterville, which has a substantial Lebanese legacy.) Rafael Clariot’s sculptural lamps have a medieval feel that doesn’t fit Western sculptural sensibilities, nor are they intended to: They are geared to a Haitian concern with spiritual cleansing. And they open the door to Minter’s work.

While the exhibition narrative looks to Maine’s African American artistic communities, it is Minter who launches this entire effort well past any expectation. The basement of the meeting house is a dark space, with an exposed crumbled-seeming stone foundation and the thoroughly seasoned aesthetic of a humble building. Minter’s section on the back wall teems with dozens of paintings, assemblages, collages and carvings pressed among each other like a crowd. His paintings are mostly figurative in a sense similar to traditional paintings of Christian saints: figures in spiritual moments with a few attributes to help us understand. His painting approach is intense, high-focus and detailed. His style, however, varies from cartooned simplicity to a forcefully respectful reliance on decorative line, for which Minter has a virtuoso sense. His imagery has its own set of leitmotifs, such as figures with hands spaced above and below their bellies, holding notions of home or pregnancy – of legacy and ancestry.

Works by Daniel Minter dominate one wall of the space.

On a cleansing sculptural piece, atop a tall and slender table-like plinth covered on the sides by paint-decorated fabric, a small carved figure seems to pull a long string of white beads up from the pile of dirt in the base of the plinth to the ceiling, where it bifurcates, seemingly to the sky. It is an image of ritual that is unmistakably a ritual itself. The space is cleansed, and so are you when you enter it. This is a powerful and extraordinarily unusual gesture to the viewer in Western art. Generally, non-denominational spiritual art (like Morris Graves, Mark Rothko, etc.) is mystical, unfettered by any religious apparatus and geared to the individual viewer. But Minter’s art unleashes a spiritual tsunami on all viewers of “A Distant Holla.”

Traditional spiritual experience in Western culture is associated with religions, which generally do not allow members to experience the spirituality of other practices. What makes this exhibition particularly unusual is the combination of identities and communities that are being welcomed together spiritually. The people gathering here are clearly asserting their sense of “other” in Maine – it is the essence of the Abyssinian Meeting House: a place for the “others.” And yet African Americans and black culture comprise robust and storied facets of the Portland and Maine communities. This is a show about Maine as much as anything else, and it is for Mainers.

One of Titi de Baccarat’s painting-like installations.

What’s more, the spirituality of the African diaspora is quite different from most mainstream religions. (The broadest comparison is with Judaism, which combines race, culture and community with religious practice. Consider, for example, Richard Brown Lethem’s work now on view at the nearby Maine Jewish Museum. It includes a work titled “Slaveship,” which was inspired by the image of a slaveship, targeted for abolishment, hanging on a meetinghouse wall. I visited these shows on the same day and was richly rewarded for it.)

Minter’s spirituality appears in terms of his Southern roots and the vestiges, relics and bits of African spirituality that are still visible in contemporary ritual practice and symbolism. Minter’s works are loaded with archaeological logic, ancestor worship and contemporary cultural practices informed by past spiritual practices – like jazz musicians. The relics, too, seem humble but they burst forth with unexpected power: One piece includes a stove burner top, bits of linoleum flooring, an old hair curler and two images of women, one with straightened hair. We are transported to a humble old kitchen of long ago and the hair-styling practices of black women, and within this secular scene is a wellspring of spirit that practically crackles with intensity.

A blue sculptural lamp by Rafael Clariot illuminates the scene on opening night of “A Distant Holla” at the Abyssinian Meeting House in Portland.

When I have seen Minter’s work at Greenhut Galleries (you can see works by Driskell and Bryan there, as well), it’s easy to recognize his narrative ability. But in “A Distant Holla,” Minter is at his full power, and it’s not something we see typically on the artificial stage of a gallery. It’s real.

Bryan’s print “Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel” is from his book illustrating Negro spirituals. It depicts an angel watching over Daniel in the lion’s den. It is worth considering notions that go well past the work’s name: To be in a place where you are not like the others is not only a question of danger, but of identity and faith. And Bryan reminds us that the stories of others apply to us as well. Our stories contain our culture, our identities and our faith.

“A Distant Holla” may look back to the past, but it is very much about who we are as Mainers and Americans today.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.