Writing poetry is a little like praying. “You talk to yourself with an imaginary listener,” said Wesley McNair, Maine’s former poet laureate, whose new collection, “The Unfastening,” reflects his prayerful, private conversations about the death of his mother and the decline of family elders.

Written over several years, the poems explore McNair’s loss and despair, as well as his recovery and feelings of hope. “I wanted to talk to myself about all of these things,” he said over lunch at his favorite Indian restaurant in Waterville. “A poem always begins with a feeling so deeply felt that if you had a stick and stone you’d make words from them. As artists, we all have to submit to this feeling.”

“The Unfastening” is McNair’s 10th book of poetry and the second about his mother and her family legacy. “The Lost Child: Ozark Poems,” from 2014, was McNair’s first trip down this path, when he rediscovered his Ozark past as he carried his mother’s ashes home to southern Missouri from New Hampshire, where she lived most of her life and where she raised McNair. “The Lost Child” poems were long-form reflections on his mother’s journey home and his own reconciliations associated with it.

The poems in “The Unfastening” are much shorter and more direct about the cycle of life and the grief and affirmation that accompany it. “We’re all going through it,” McNair said. “Heartbreak, however hard it is to go through, is one of the main avenues to humanity.”

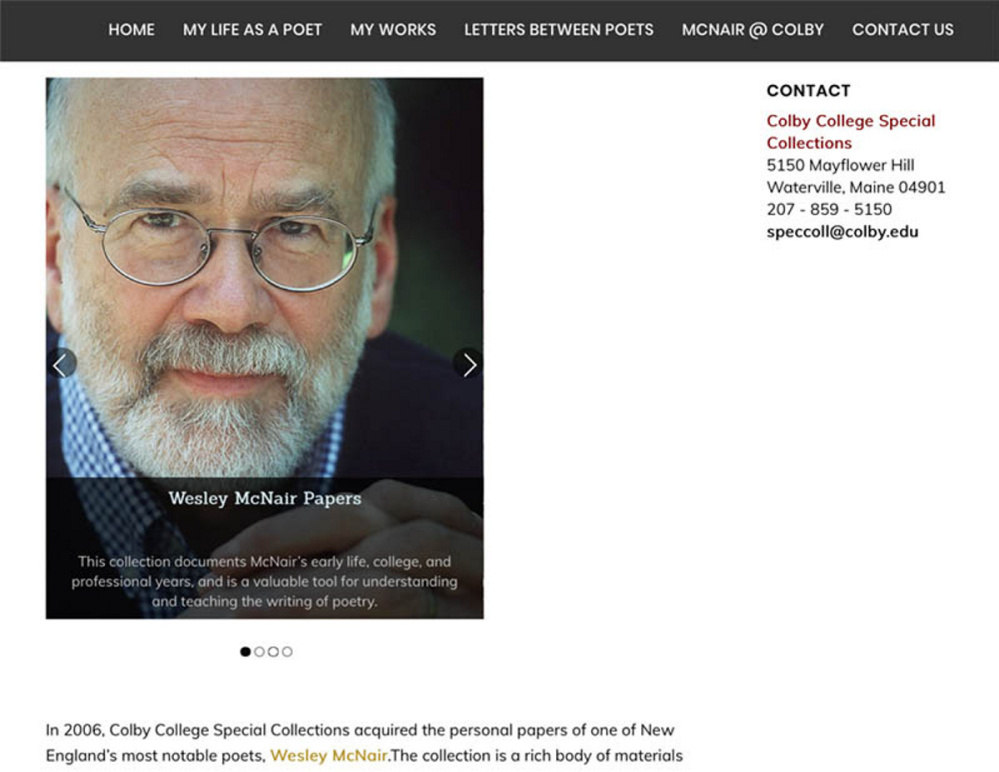

McNair, who lives in Mercer and serves as professor emeritus and writer-in-residence at the University of Maine Farmington, teamed up with the Special Collections department at Colby College to create a website for “The Unfastening” that helps readers understand his creative process and expands the way people can experience poetry. It also provides an insider’s view of how a book comes together.

The website will officially launch at 4 p.m. Friday. A reading by McNair scheduled for that time was postponed because of illness, and will be rescheduled. Patricia Burdick, Colby’s Special Collections director, said the website is designed to complement the published book by providing a digital platform for the humanities, with students, teachers, other poets and general readers in mind.

There are audio clips of McNair reading, a transcript of an interview and a revealing string of emails between McNair and cover illustrator Robert Brinkerhoff that spotlights how artists collaborate and the inherent reward and tension of the process.

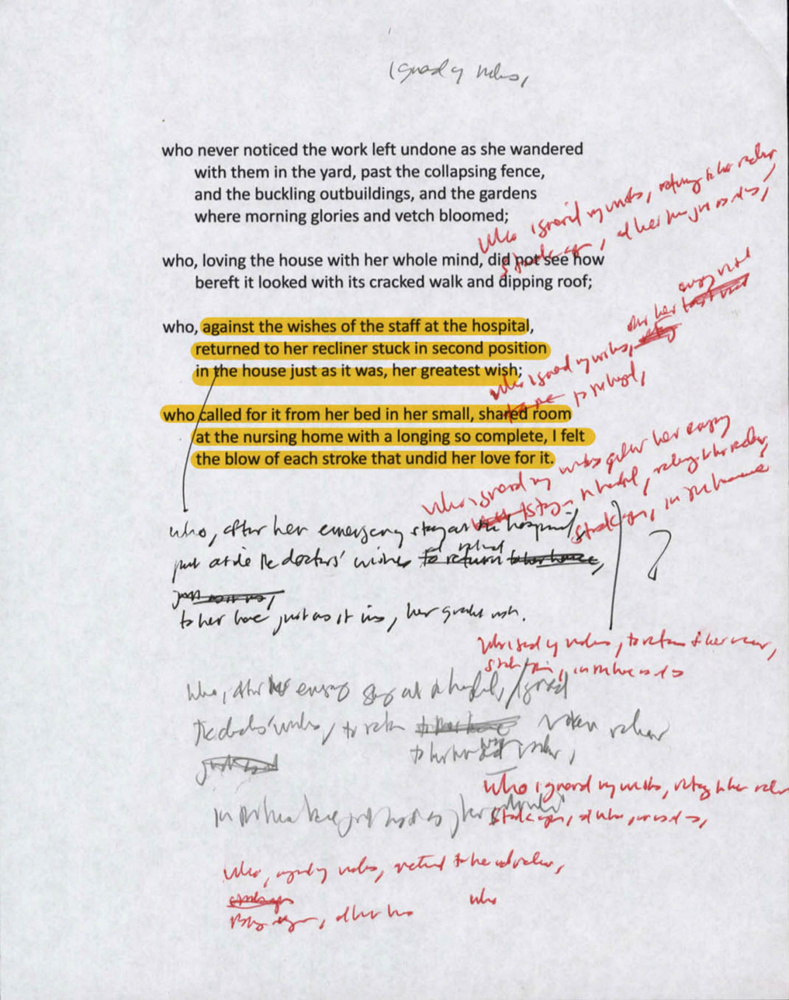

The website tracks McNair’s drafts of the poems, with his notes and revisions. In doing so, it demonstrates the evolution of a poem from first draft to final version and provides a visual representation of a poem that isn’t part of the published book. With McNair’s voice as a soundtrack and the personal touch of his craft peppered throughout, the website offers the anatomy of a poem, a book and a creative mind. The project required the cooperation of McNair and the coordination of a Colby team of archivists, tech-based educators and student interns.

McNair has a decade-plus history with Colby. In 2006, Colby College Special Collections acquired the poet’s personal papers, including scrapbooks, photographs, family letters, teaching notes, poem drafts and manuscripts, audio-visual materials and correspondence with colleagues and peers. The website enriches the collection by creating more digital access, Burdick said. “It documents the daily life of a busy poet,” she said.

McNair, 76, is one of Maine’s most decorated artists. He has won fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities, the Guggenheim and Fulbright foundations, and a $50,000 United States Artists Fellowship. “The Lost Child: Ozark Poems” won a 2015 PEN New England Award for Poetry, and four times he has served on the Pulitzer Prize jury for poetry; 22 times, Garrison Keillor has read McNair’s poems on “The Writer’s Almanac.”

He was Maine’s poet laureate from 2011 to 2016.

“The Unfastening” was a hard book for McNair to write because it’s so personal. He’s been working on it since 2012, when his mother died. Much of his writing from that period ended up in his long-form collection of Ozark poems, but he persisted on these more personal, shorter poems.

They began as poems of grief – deeply remorseful purges, loving remembrances and aching glimpses of lives in decline. He wrote about his dying mother “after the nurses turned her stiff body toward me in her bed”; of an uncle’s stroke, a proud military man “now unable to tuck himself, or trust his slack tongue”; and of the sadness of nursing homes:

It stops at each door:

an ice-cream truck with no bell,

just pills, a clipboard.

He wrote about the misfortunes of his neighbors in “The Rhubarb Route,” recalling a robust community of older folks near his Mercer home, to whom he delivered rhubarb “between the black fly season and first mosquitoes.” He’s had to give up the spring routine because all the older people in town who understood what rhubarb is, and what to do with it, are gone.

It all left him numb and sad, until eventually McNair moved through his grief and began to see the world in different colors. His poems shifted from sickness and dark to healing and light. His book turned.

He wrote about his memories of his mother’s harvest centerpiece, about turning off the GPS and getting lost with his wife on a rural road, and an honest series of vignettes that describe small-town Maine, in “Maintaining”:

By the register at the store, truckers,

carpenters and mill workers

count their change while telling

the morning clerk how they are:

“Not too bad.” “Could be worse.”

“Maintaining.”

McNair closes the book with a poem called “Benediction.” Its title implies hopeful blessings: lilies of the field, black-eyed Susans, Queen Anne’s Lace.

Consider the frosted heads

of the goldenrods

bending down to the ground

and the milkweeds standing

straight up, giving themselves away.

At a reading at York County Community College, McNair told the audience he found the purpose in his book not in its beginning or end, but in the totality of its emotions. “The story I was trying to tell was not only about loss and despair,” he said, “but how to recover from those things and be a hopeful person.”

“The Unfastening,” ultimately, is about letting go. “This is not a young man’s book,” McNair said. “What aging has done for me, it has opened my heart. Poetry insists on that, always.”

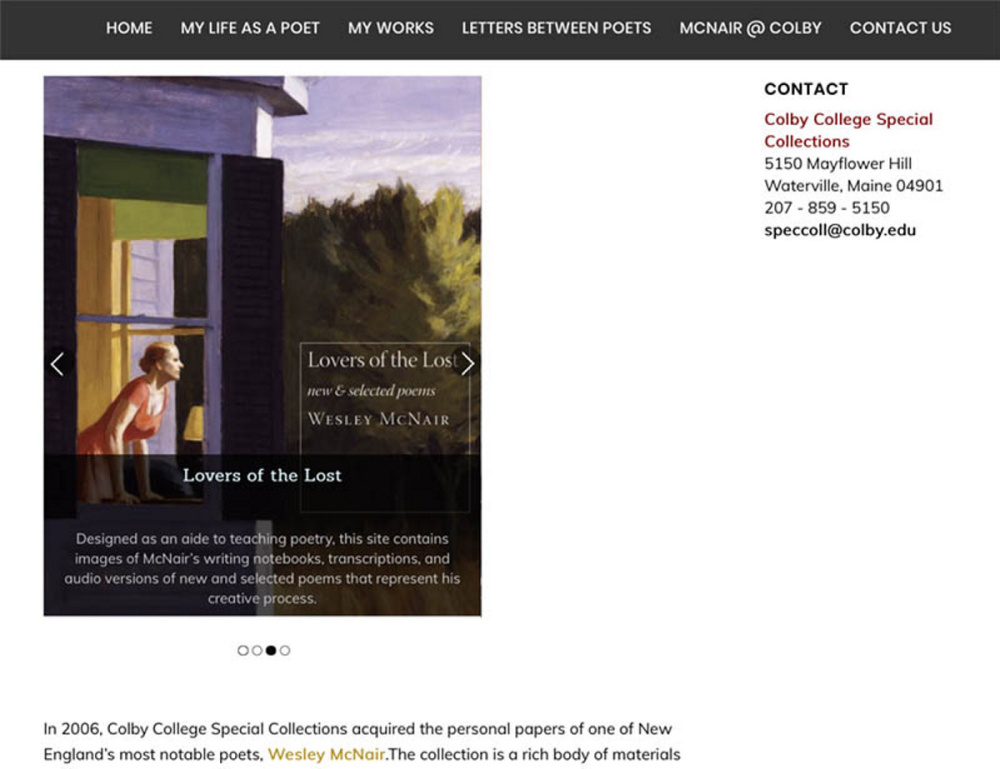

Brinkerhoff’s cover illustration shows a worn-down man trudging toward a worn-down barn on a late-fall afternoon. There are snowflakes and crows in the air.

The man hangs his head in despair, unable to see what lies ahead. McNair saw a lot of himself in that image when Brinkerhoff sent it for consideration. That’s how McNair felt for a while, until he lifted his head and began looking up.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.