BIDDEFORD — Patsy Gendron’s students pushed their arms above their heads, wiggling their fingers to get her attention as she added to a growing list of words associated with Thanksgiving.

Turkey. Stuffing. Family.

They broke into fits of giggles when one girl, searching her memory for the word “Pilgrim,” called out “penguins.”

For new Mainers like the 12 sixth-graders in Gendron’s class for English language learners at Biddeford Middle School, Thanksgiving provided an opportunity for a fun lesson about an American tradition and its similarities to holidays and feasts they celebrate with their families. Conversations that involve different cultures, religions and languages are increasingly common in Biddeford schools as the student population grows to include more immigrants, refugees and migrants whose families are settling in the city.

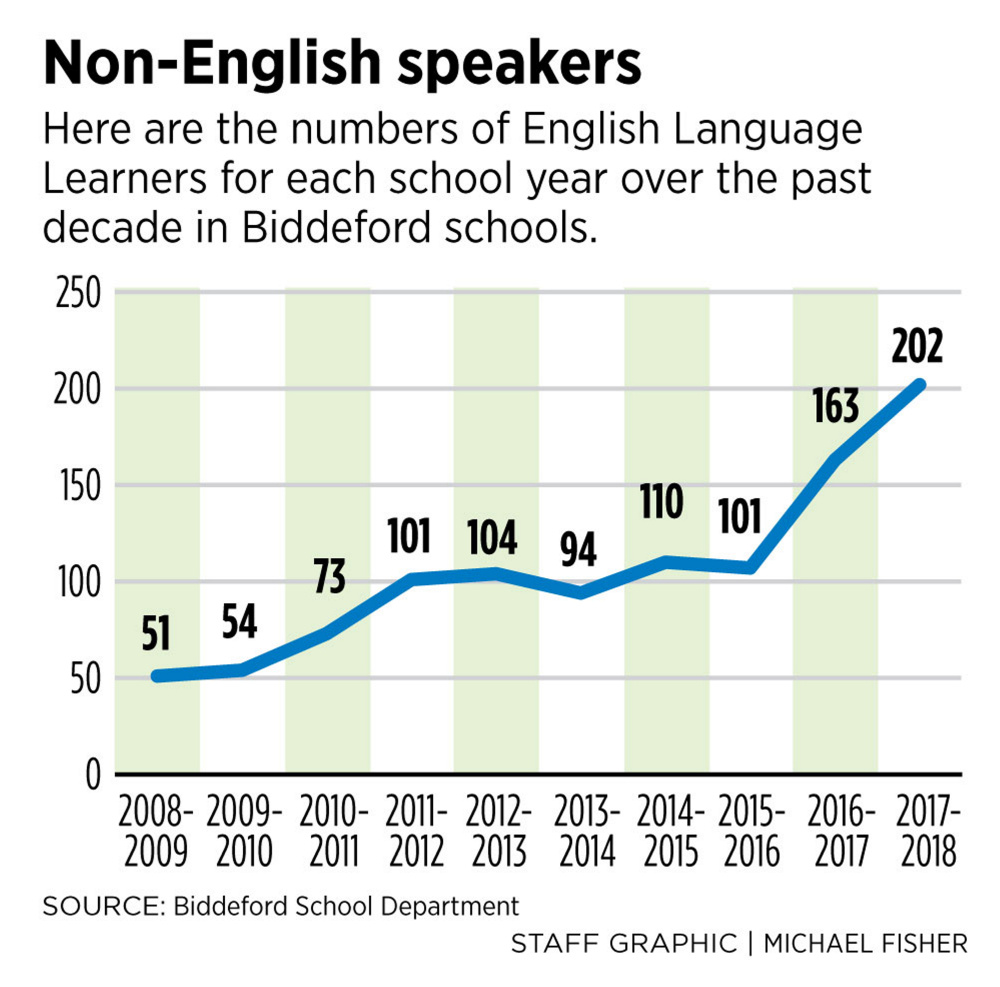

The number of English language learners in Biddeford has doubled in the past two years as families move from outside the United States or from other areas of the state. It is the latest Maine community to see a significant increase in students who speak little or no English.

Families are drawn to Biddeford as a safe city with good schools and access to jobs and transportation, and as a community that has been welcoming, say students, parents and school officials who spoke at a recent community gathering.

Over half of the English language learners in York County now attend Biddeford schools, which has more than 200 students from 20 countries this year. They speak a total of 22 languages. Arabic is the most common, with 111 students identifying it as their native language.

Some of the 202 English language learners, or ELL students, came to Biddeford knowing some English, while others have had interrupted schooling or have never attended school before.

The influx of students who are not native English speakers has both “extraordinary” benefits and challenges, said Assistant Superintendent Chris Indorf, who oversees the ELL teaching staff and curriculum. Students who come to Maine from other countries bring with them different worldviews, cultures and religions, he said.

“It’s a living curriculum,” Indorf said. “You can’t get that out of a history book.”

‘THESE STUDENTS ENRICH OUR SCHOOLS’

To meet the needs of new students, the district has more than doubled its staff of ELL instructors to eight. Indorf said he is in the process of hiring a ninth instructor, and he hopes to add a 10th during the upcoming budget process. The ELL instructors and all other teachers and staff have worked together to learn about cultural and religious differences and how to teach students with limited English skills, he said.

Indorf said that learning takes many forms: In some cases, it’s learning that a student being disciplined may not look the teacher in the eyes because in their culture that is not appropriate. It also means understanding that some students have endured hard and emotional journeys to get to Maine, often fleeing war and being separated from extended family.

“For us to be able to serve kids who come to us from war-torn countries or who cannot speak the language or who can’t eat the meat in the cafeteria, we have a ton to learn,” Indorf said. “We have a moral imperative as educators to do this.”

Superintendent Jeremy Ray said he knows the increase of students with limited English proficiency brings unique challenges, “but these are challenges we want to work on.”

“These students enrich our schools, enliven our curriculum and enhance the quality and diversity of our schools,” he said. “Their families have a parallel impact on our community.”

CREATING COMMUNITY

To bring the schools and “new Mainers” in Biddeford together, the school department last week launched a new initiative, Biddeford Rising, in collaboration with Spurwink, the behavioral health and education services nonprofit. The community-based Biddeford Rising is modeled after a similar school-to-home program in Portland, which, like Lewiston, Westbrook and South Portland, has also seen a surge in the number of students who speak languages other than English.

As students and their parents streamed into the school gym, Khulood Al Hasan greeted many of them by name and helped translate for Arabic speakers when needed. Al Hasan, an education technician at the middle and high schools, moved to Maine from Iraq two years ago with her two children and her husband, who was an Army translator and now works as an interpreter with Catholic Charities. She taught high school math for 12 years in Iraq.

Al Hasan said Biddeford Rising is a nice way to bring people together, especially families that don’t understand English.

“It’s important to connect people,” she said.

During the meeting, families and school employees sat together at long tables to talk about what Biddeford schools are doing right and what can be done better to make everyone feel welcome. Parents described finding a school community with honest teachers who are respectful to parents and students, and said their children enjoy going to school. They said they feel welcome in Biddeford, but sometimes feel like they’re learning English in slow motion.

Despite their enthusiasm for the schools, parents told Indorf and other school officials there are still challenges they’re trying to overcome as they settle in Biddeford. The local public transportation can be confusing, jobs are not always easy to find and heat is expensive. They also said their children run into cultural restrictions with food served in the school cafeterias. Students often eat a lot of pizza to stay away from meat, because it is not prepared in a way that meets their needs.

Best friends Rusul Ahmed, 17, and Mariam Gassab, 19, sat together, chatting easily with community members who asked them questions about their native Iraq, their journeys to Maine and their thoughts on attending Biddeford High School.

Ahmed, a junior, came to Maine two years ago and settled first in Westbrook before her family moved to Biddeford. She did not speak any English when she arrived and would say “yes” to every question. Two years later, she is a member of multiple school clubs and plans to attend college to become a dentist.

Ahmed said the first big challenge she and other non-native Mainers face is learning English.

In Biddeford, Ahmed said it has been easier to learn English because she is in mainstream classes with American students and not surrounded all day by other Arabic speakers. After learning English, the next big challenge is helping other people “understand why we are here” so they do not bully or discriminate against new members of the community, Ahmed said.

“We have to teach people why we came here and what I’ve done with my life,” she said.

‘TALK ABOUT RESILIENT KIDS’

Gendron, the middle school teacher, has been an educator for 22 years and is now in her third year teaching English language learners. She said she has “learned so much” from her roughly 50 students, who came to Maine from Iraq, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Jamaica, El Salvador, Ivory Coast, South Sudan, Ghana, Burundi, Tanzania, Rwanda, United Arab Emirates, Cambodia, Vietnam, China and the Philippines.

A map on her classroom wall includes a photo of each student and a string connecting them to their native country.

“Talk about resilient kids who are really motivated and have a passion to learn,” Gendron said. “You would never know looking at them the stories behind these students. They are really something special.”

English language learners at the middle school have a reading and writing class with Gendron, plus a learning lab where they get help with other subjects. Every lesson in her class includes reading, writing, listening and speaking. She tries to use a lot of visuals, as do teachers of other subjects with ELL students in their classrooms.

Gendron said ELL students spend most of their time in mainstream classrooms, which allows them to connect with their peers and do important learning about how the school works, how to get to classes and even how to open their lockers.

“The social language is the first language,” she said.

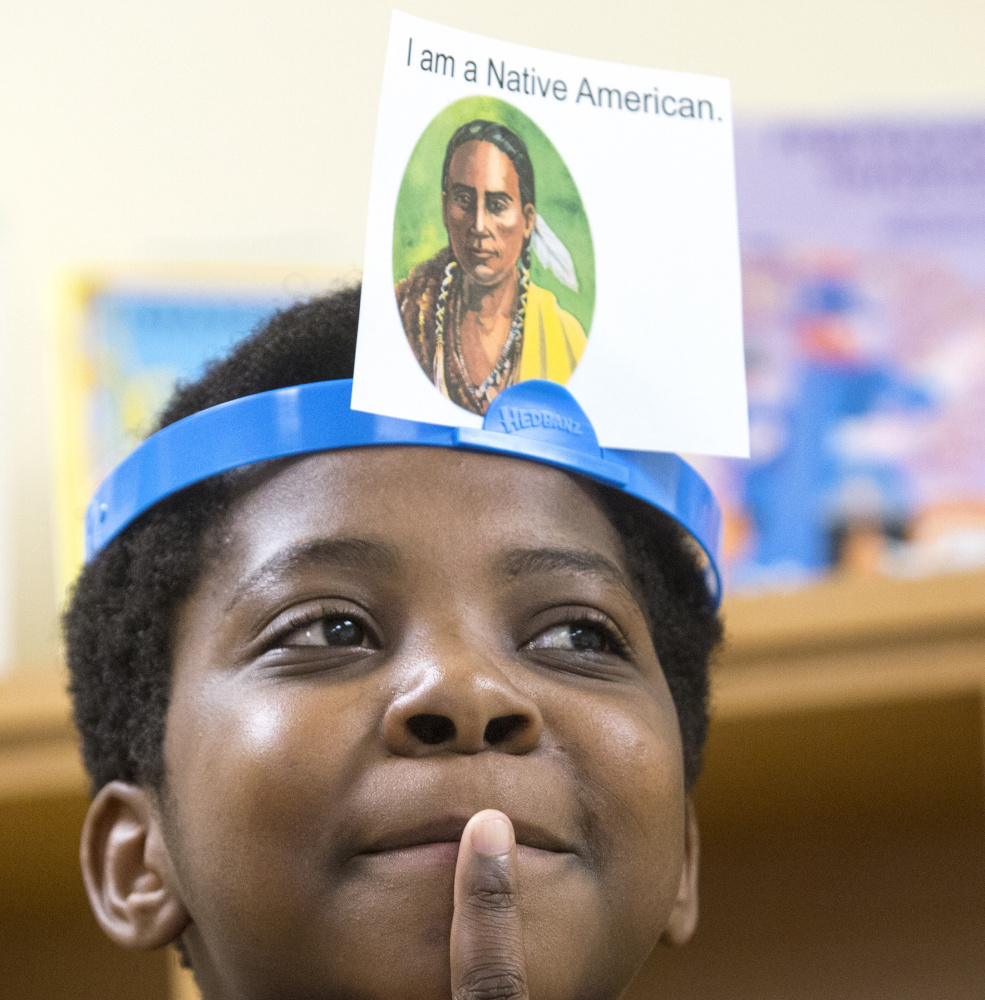

During the last class before Thanksgiving break, students played the game “Hedbanz” with the holiday-themed words they brainstormed at the start of the class. Students took turns standing at the head of their work table trying to guess the image on the card attached to their head.

Fatima Gassab, 11, wiggled her eyebrows at her classmates as Gendron attached a card showing a picture of an ear of corn to the headband strapped around her forehead. She asked a series of yes-or-no questions: Is it an animal? Does it have legs? Does it have hair? (Yes, they told her). Ultimately, she figured out it was a food product, but never guessed corn.

“That does NOT have hair!” Fatima told her classmates as she headed back to her seat.

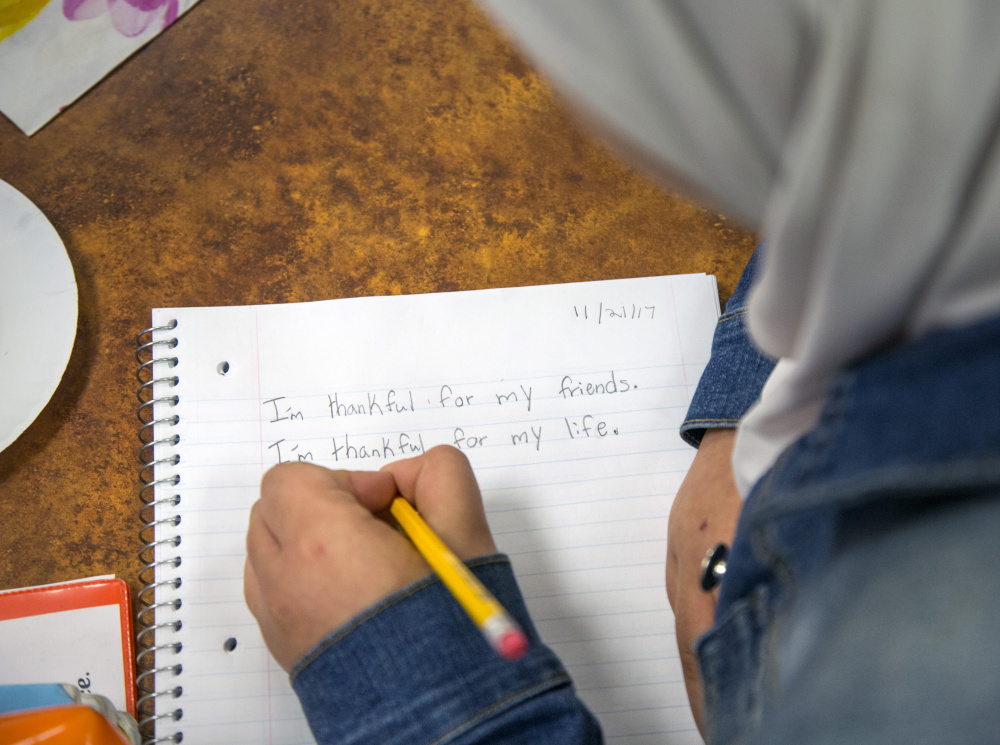

After sampling homemade cranberry sauce – most had never tried cranberries – the students and Gendron talked about what it means to be thankful. The room grew quiet as students focused on writing out lists of the things they are most thankful for in their lives.

Rawan Ahmed, 11, who is originally from Iraq, printed neatly in her notebook that she is thankful for her friends, her life and “to have the nicest brothers, sisters, mom, dad.”

Like many of his classmates, Huseen Saad, 12, said he is thankful for his parents, his brothers and sister, and God.

“I’m thankful all of my family is alive,” he said.

PressHerald.com disables reader comments on certain news stories, including those dealing with sexual assault and other violent crimes, personal tragedy, racism and other forms of discrimination.

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.