Photographer Shoshannah White captured a series of images above the Arctic Circle during a residency based in Svalbard, Norway. I have been intrigued with this body of work when I have seen some of it before in exhibitions at Corey Daniels Gallery in Wells and Space Gallery in Portland. But with the exhibition “Strata” at the Maine Jewish Museum, the work came into clear focus for me.

The Space show played up the collaborative qualities of the experience while Daniels’s presentation featured the ability of the work to stand on its own as individual artistic objects. Both were successful presentations. But the Maine Jewish Museum exhibition gets at an underlying stream of content about the earth and its processes that could change how you think about geological time as it relates to natural aesthetics.

White’s images fall into several pairs of categories. Some are landscape images, while others lack a horizon line. Some are made with cameras with lenses, while others are photograms, made directly on light-sensitized photo paper. Many of White’s works look like paintings because their surfaces are covered with encaustic, an ancient wax-paint medium that gives a foggy, unified field when applied over photographs. Because the wax is transparent and melts (and can be remelted), it is ideal for blending in things like pigment — or, in this case, coal dust.

Encaustic (which, intriguingly, in Greek means “to burn in”) is also compatible with oil paint. White uses oil paint, metal dust, metal leaf and photographs in most of the works in “Strata.” So while she could refer to these works as, say, “mixed-media on panel,” she is clear these are fundamentally photographic works. (Encaustic can be abused by artists who let viewers think the included photos or prints are painted elements, so I appreciate White’s transparency.)

“Coraholmen, Reflected #2,” for example, is a large, square image of a glacier. It is a photo mounted on a panel with encaustic over it, metal dust, coal dust and metal leaf used largely near the edges to give the sense the work is mounted on an inorganic support, like aluminum. The image is overarchingly bathed in a snowy gray-white light. What brings the scene into focus are the horizontal dark bands of sediment (strata) on the mountain-like glacier. The spatial symmetry of the image’s horizontality is emphasized by three implied flat systems: the bands in the glacier, the reflection of that in the water, and then the horizon line of the landscape created and enforced by the single-point perspective of the camera.

White’s use of metal is part of a subtle shunning of organic materials or processes. We are used to seeing landscapes as places of life: trees in a forest, flowery fields, teeming lakes and so on. What we are seeing here are inorganic processes — the earth as a mineral planet rather than an organic one.

White’s adding coal into the mix enriches this approach. Coal, after all, is the mineral reclamation of organic material: We know we’re carbon-based life forms, but we rarely think about it. The coal process, however, doesn’t work in organic time — the minor sets of years of living things — but instead in geologic time. There is a reason for the analogy “glacial pace,” after all. A typical glacier only moves about 2 feet a day. Coal is far slower: The “freshest” coal is many millions of years old.

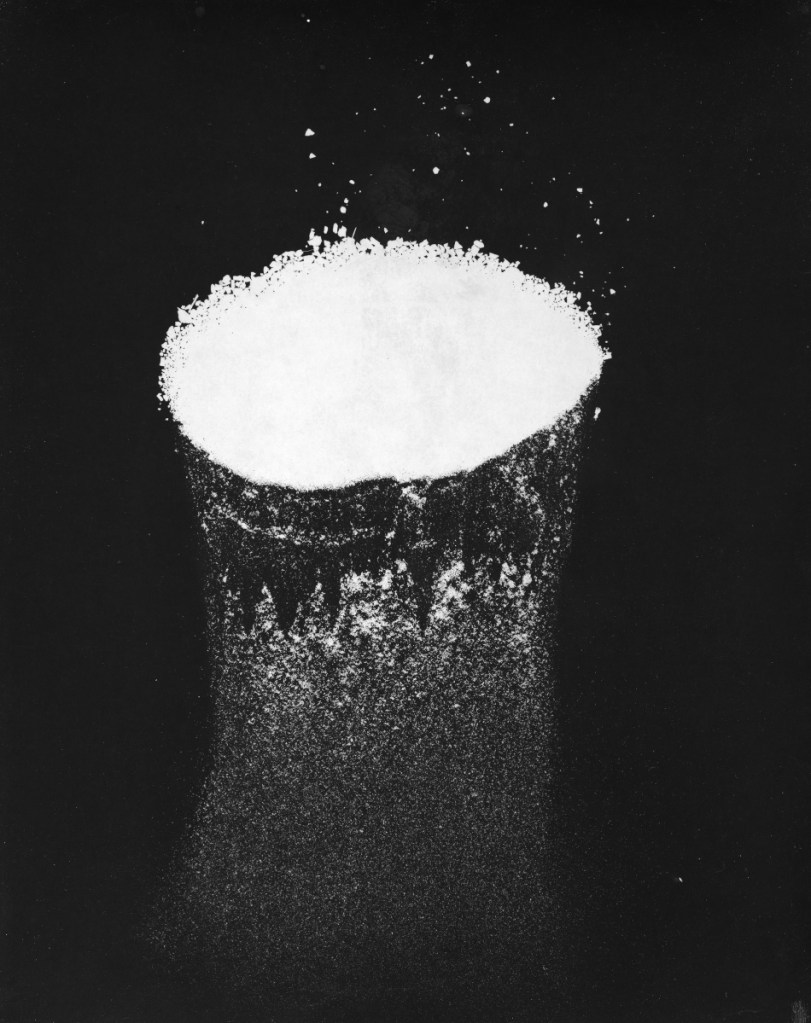

The converse is that White takes glacial ice and lets it melt to make a real-time photogram. There is a palpable disconnect between the speed with which human processes can make glacial ice melt and the mineral/geological processes that created the glaciers in the first place.

Glacial ice is actually much younger than we tend to imagine it is (typically about 100 years old), but its processes are dynamic and offer a sense of life to the inorganic mineral reality of the earth: Glaciers are driven by pressure-creating gravity and mass. Coal, too, is created by pressure and gravity.

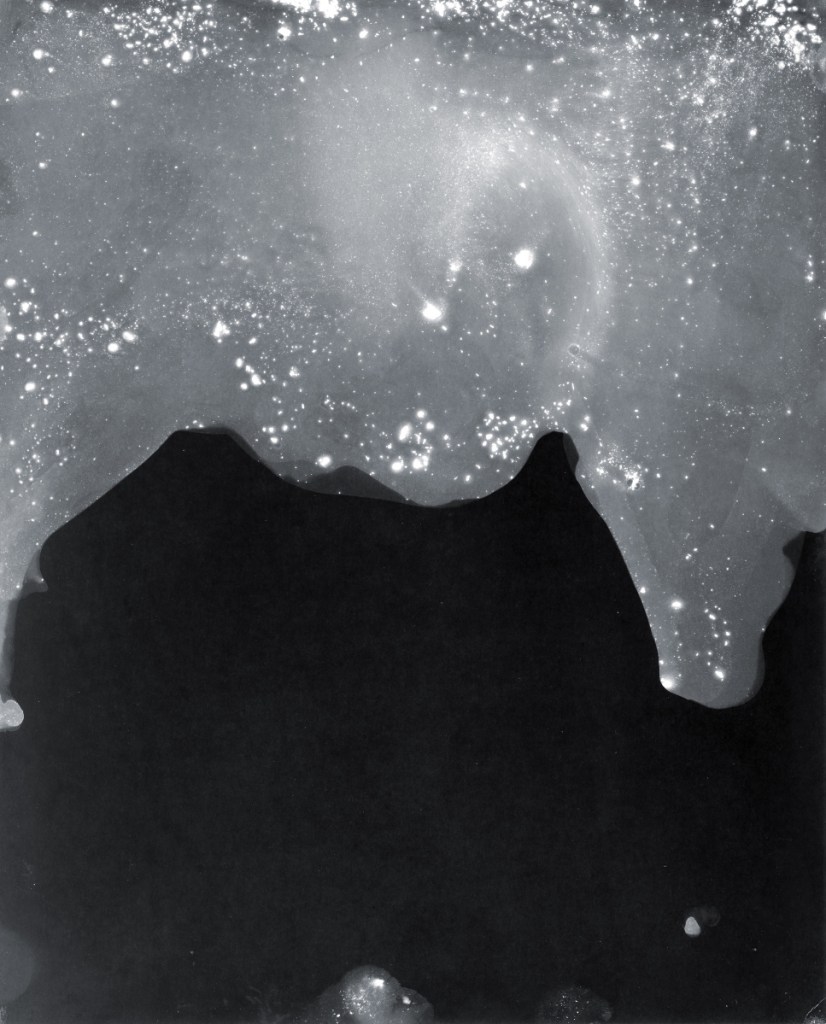

Some of White’s images, such as the person-tall “Coal Landscape,” reflect an aesthetic that matches the worlds of both micro and macro physics. The basic idea is that images of dust and the stars in the sky often look very similar because of how they play out the laws of physics on the same terms. The effect of this is to knit together the images of coal and water as mirroring the processes of the cosmos. White’s handling of this is quiet, powerful and meditatively beautiful.

White’s presentation of some chunks of coal on tiny but handsome customized shelves might seem gratuitous at first, but the effect comes into focus as you take in the content of the show.

White’s installation reflects her concern with the role of aesthetics in her art. Her attention to surface, image quality, composition of elements on the wall and framing goes much further than trying to make an attractive installation, though it is. Rather, White is challenging us to find repeated visual qualities and constants — superficially, the stuff of style, but more deeply, the observational aspects of science.

White might be driven by a political or environmental agenda, I don’t know, but certainly nothing like that interrupts her meditations on perspective. Her work is sensory and aesthetic. It is thoughtful but fundamentally free of verbal persuasion. I saw “Strata” during the opening, and it certainly inspired rich conversations. But I also saw it when I was alone in the gallery, and, to me, that was preferable and proffered a much richer experience. White, after all, is challenging us to stop seeing with our mouths and think visually.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.