The moment he saw the brilliant light captured by his camera, “it all clicked” for Victor Buso: All the times his parents woke him before sunrise to gaze at the stars, all the energy he had poured into constructing an observatory atop his home, all the hours he had spent trying to parse meaning from the dim glow of distant suns.

“In many moments you search and ask yourself, why do I do this?” Buso said via email. This was why: Buso, a self-taught astronomer, had just witnessed the surge of light at the birth of a supernova – something no other human, not even a professional scientist, had seen.

Alone on his rooftop, the star-strewn sky arced above him, the rest of the world sleeping below, Buso began to jump for joy.

Buso’s discovery, which was reported Wednesday in the journal Nature, is a landmark for astronomy.

His images are the first to capture the brief “shock breakout” phase of a supernova, when a wave of energy rolls from a star’s core to its exterior just before the star explodes. Computer models had suggested the existence of this phase, but no one had witnessed it.

“In our field, this is a fundamental question: What is the structure of the star at the moment of explosion?” said Melina Bersten, an astrophysicist at the Institute of Astrophysics of La Plata in Argentina and the lead author of the report.

With Buso’s observations, scientists can begin to answer that.

TINY LIGHT GROWS BRIGHTER

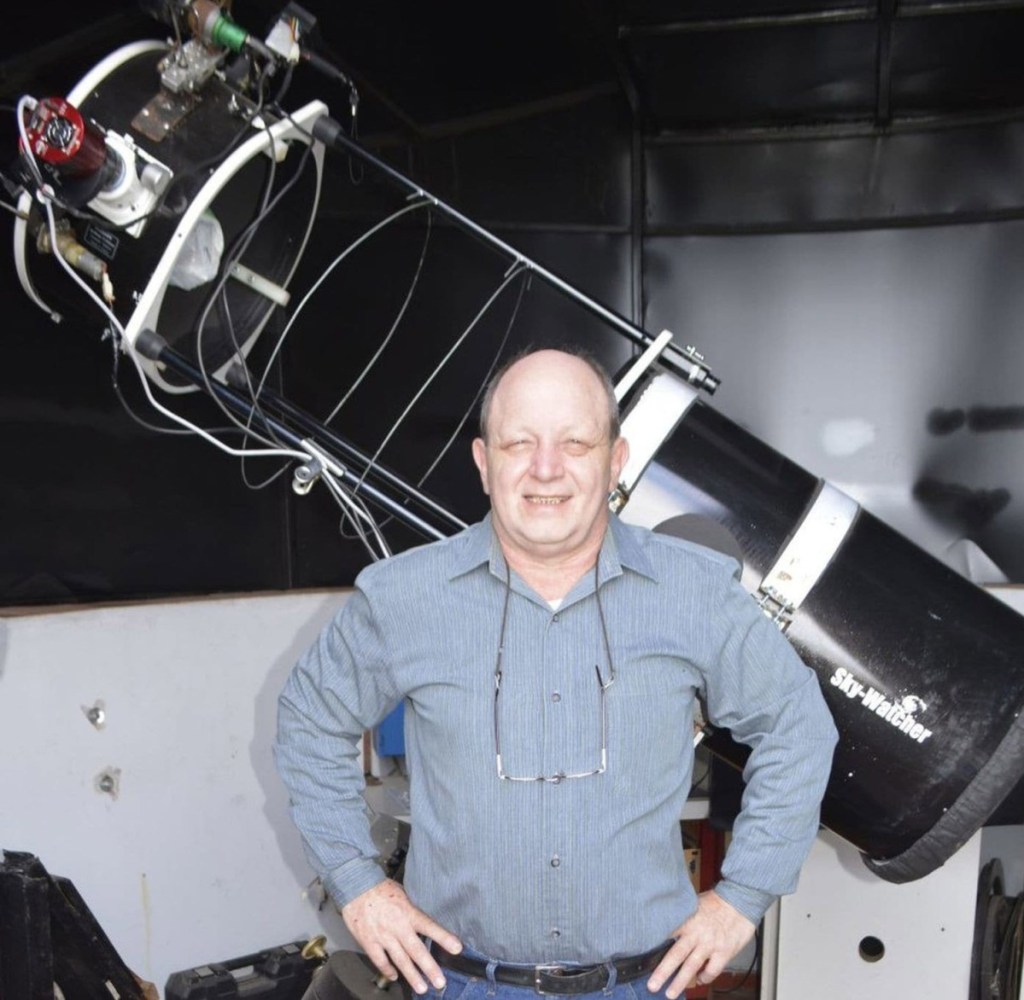

Buso, a 58-year-old locksmith from the Argentine city of Rosario, inherited his love of astronomy from his parents.

When he was 10, his father roused him from bed to glimpse Comet Bennett streaking across the sky. The year before, his mother had held him at her side in front of the family’s television to watch Neil Armstrong take humankind’s first steps on the moon. “Vitito,” she told him, using his nickname, “you have to see this moment. You will never forget it.”

Buso began building telescopes at age 11, using tin cans, magnifying glass lenses and Play-Doh to make the stars seem closer. Eight years ago, he sold a piece of land he owned with his father and used the proceeds to construct an astronomy tower on his roof. He calls it Observatorio Busoniano.

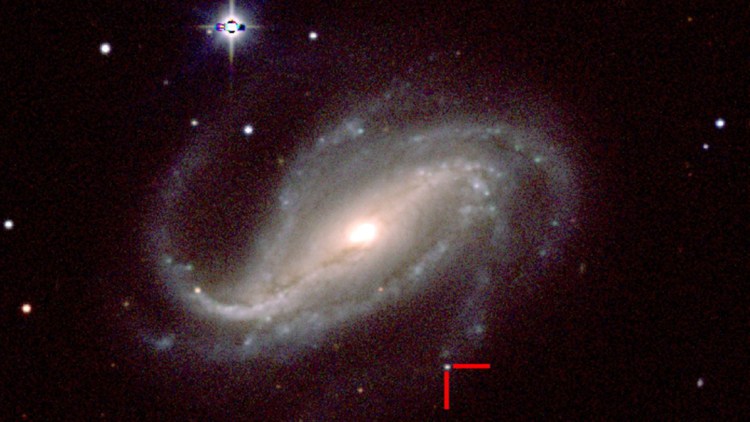

These days Buso prefers to scan the skies with cameras mounted atop his 40-centimeter telescope, which allows him to observe phenomena too faint to be spotted by eye. On the evening of Sept. 20, 2016, he decided to test a new camera by pointing it at NGC-613 – a barred spiral galaxy about 65 million light-years from Earth.

Within a few minutes, he noticed something strange in his photographs: a tiny pixel of light that didn’t appear in archive images he found online.

“I thought, ‘Oh, my God, what is this?’ ” Buso recalled.

The light didn’t look like a supernova – the usual source of new lights in the sky. (Indeed, “nova” means new star, though supernovas are the explosive deaths of suns that have run out of fuel.) Yet the light just kept getting brighter.

Buso realized he needed to show this to a professional, but most of Argentina’s astronomers were at an annual conference far from the nearest observatory. He finally got in touch with a fellow amateur, who confirmed the sighting and helped him develop an international alert with data Buso provided on the object’s position, brightness and timeline.

As soon as darkness fell the next night, Buso rushed to his roof to see whether that faint pixel had developed into a brilliant, full-blown supernova.

It had.

Buso’s images made their way into the hands of Bersten and her colleague Gaston Folatelli, who could hardly believe what they were seeing.

suPERNOVA’S FIRST HOUR

“We immediately noticed this was an incredibly important discovery,” Bersten said. “Given that we don’t know where and in which moment a supernova is going to explode, it is very easy to lose this very fast early phase.”

According to a statement from the University of California at Berkeley, Buso had captured light from the supernova’s first hour. Bersten estimated the chance of happening upon such an event at about 1 in 10 million.

Using powerful telescopes to observe the supernova in multiple wavelengths, the astronomers detected the light signature of a star that had lost most of its hydrogen envelope, then exploded.

This gave them insight into the structure of the progenitor star, which Bersten and her colleagues concluded was a yellow supergiant about 20 times as massive as our sun. It was probably in a binary system, they say, because such stars rarely blow up on their own.

The early detection also allowed the scientists to track the supernova throughout its evolution and develop models to explain what they saw. Even now, they continue to scrutinize the explosion; knowing how this star died might shed light on how it lived.

Stellar explosions “come in different flavors,” Folatelli explained in a call from Argentina several days ago. “We want to know how stars evolve into the different structures that give different outcomes in supernovas.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.