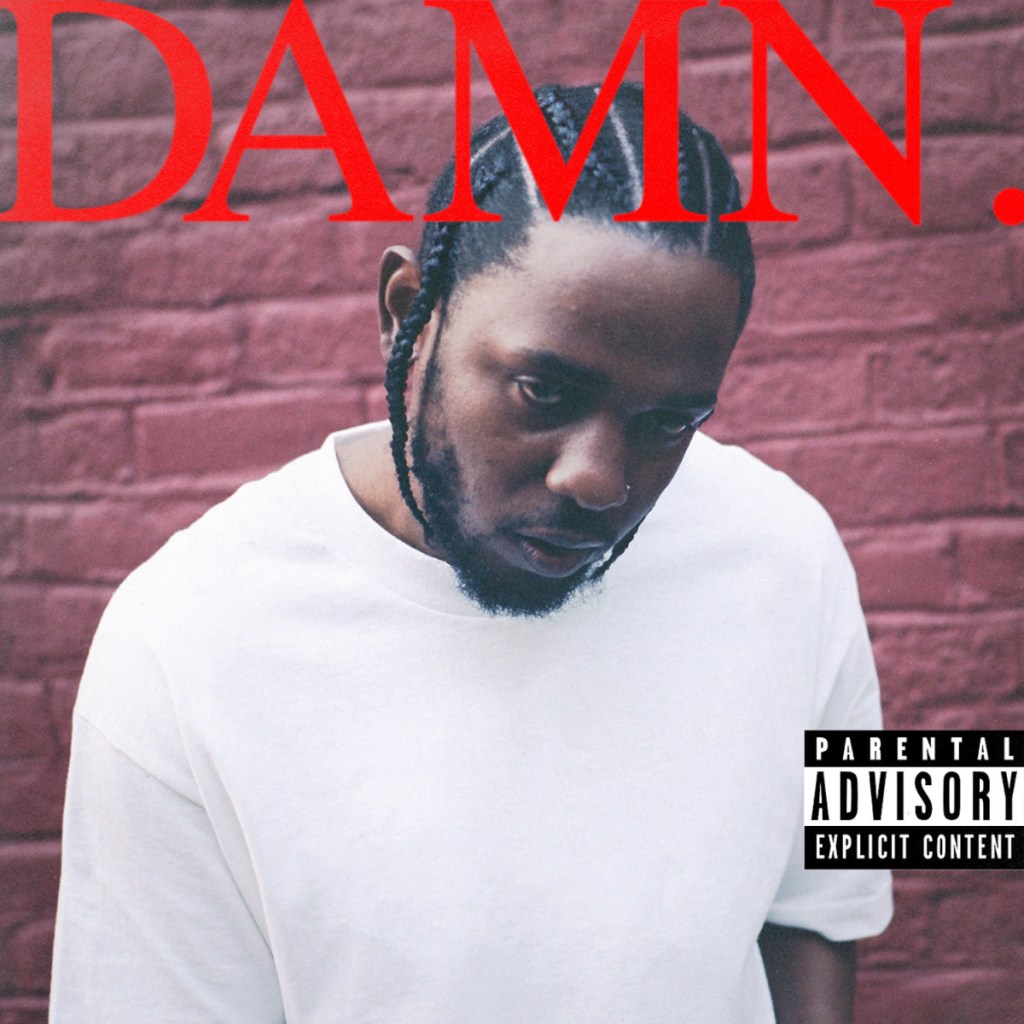

When the Pulitzer Prizes were announced this month, few felt more genuinely surprising or groundbreaking than the prize for music, which was awarded to the rapper Kendrick Lamar for his album “DAMN.”

It was a groundbreaking decision for the Pulitzer committee – which had never recognized a rap or hip-hop artist – one that placed the Pulitzers squarely in the mainstream of American popular culture and ahead of other, supposedly more hip awards-giving bodies such as the Recording Academy.

The refreshingly straightforward explanation of how the Pulitzer jurors made their recommendation signaled a welcome willingness to consider the sorts of music that haven’t typically been in Pulitzer contention before. But Lamar’s win also provoked a certain amount of anxiety in the classical and new-music communities, which have traditionally dominated the Pulitzer music category.

To learn more about that response, I chatted with the composer, writer and performer Alex Temple, who I’ve known since college, and who introduced me to musicians such as John Cage. We talked about generational divides in the classical and new-music communities, the economic pressures artists face, and what classical and new musicians can learn from Lamar’s Pulitzer victory.

Q: When Kendrick Lamar’s “DAMN.” won the Pulitzer Prize for music, the reaction I saw among the pop music critics and fans I read and follow was basically unanimously enthusiastic. People were thrilled the Pulitzer committee seemed to be showing an openness to, and curiosity about, musical forms they hadn’t previously considered as parts of the awards process, and were delighted for Lamar in particular, given the significance of the album. But I don’t follow conversations about classical and new music nearly as closely, nor am I necessarily wired in to conversations among composers working in those arenas. So how did you see people working in and talking about those genres react to the Pulitzer?

A: All over the map. A lot of people are very enthusiastic about Kendrick’s win, saying that it’s about time the Pulitzer moved beyond its limited focus on contemporary classical music and, for the most part, on work by white men. On the other side, there are people saying that hip-hop doesn’t even count as music; I even saw one trot out the old cliche that “you can’t spell ‘crap’ without ‘rap.'” And some are in the middle, appreciative of Kendrick’s work but afraid that classical music will be eclipsed if popular music has access to institutions like the Pulitzer.

Q: Where do you feel like the classical and new-music communities are in terms of the conversation about who gets to create new work, whose work gets performed, and under what circumstances? It sounds like those conversations are ongoing, obviously, but is there even a consensus – the way there is based on what the numbers show us about who gets to direct movies – that white men have historically been dominant in these genres? Or is something like that still up for dispute?

A: Sadly, we don’t yet have that consensus. Among other things, there’s a generational divide: Composers and new-music performers in their 20s and 30s are generally much more critical of classical music’s history of white male hegemony, but I’ve seen plenty of older white men react angrily and defensively to any attempt to provide more opportunities to women and people of color. In the traditional classical world, there’s also been an intense debate recently about orchestral and opera programming. Several major orchestras, including the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, haven’t programmed a single piece by a woman in their next season, which has prompted calls for a boycott.

I’d also add that, while there are plenty of well-beloved gay and (bisexual) composers, trans composers are also profoundly underrepresented, and there have been some really unfortunate depictions of trans people in works by (cisgender) composers. I’m actually giving a conference talk on the aesthetics and politics of transness in new music this weekend, partially in order to help correct that imbalance.

Q: In other words, it sounds like this year’s Pulitzer Prize for music happened right in the middle of a bunch of pre-existing debates and anxieties. Is it also your sense that younger composers are more likely to listen to and appreciate music from a wider range of genres? Do you feel like some of the older conservative composers feel a specific antipathy towards rap that they might not feel towards, say, the jazz musicians who have won the Pulitzer Prize in the past, or to honorees like Bob Dylan? When you and I were first getting to know each other in college, you introduced me both to a bunch of daring pop music I didn’t already know, and to the first new music I’d ever listened to.

A: And you got me into hip-hop! Starting with OutKast.

As for your previous question, yes, absolutely. Two jazz musicians have won the Pulitzer before – Wynton Marsalis in 1997 and Ornette Coleman in 2007 – and and while there was controversy the first time it happened, the classical world seems to have gotten used to it. A lot of older composers seem to see jazz as a legitimate art form while denying that status to hip-hop. The composers I know who are my age and younger tend to be extremely eclectic in their listening habits. (I’m 34.)

Q: Is there something about the way jazz is either written, performed or sounds that made it easier for some elements of the classical to get comfortable with the idea that jazz compositions and jazz musicians might win big prizes? Is it just sonically more comfortable? Or, to put it another way, is there something about rap that some people working in classical and new music find sonically threatening?

A: Honestly, I think a lot of it is pure stereotyping. They haven’t listened to much hip-hop, they’ve heard that it’s vulgar and simplistic, and they only listen to confirm what they already believe. For instance, I’ve seen some pretty shocking dismissals from people who listened to Kendrick for two minutes, lacking any kind of cultural or artistic context, heard some swears and an angry tone, and concluded that his music wasn’t worth listening to. They weren’t delving into the subtleties of the production, or exploring the massive web of inter-textual references, or recognizing that Kendrick often puts on other people’s personas, sometimes more than one in a single song. The funny thing is is, these same people would respond to a casual dismissal of their music by saying “you need to educate yourself.” They’re so secure in their elitist worldview that they don’t notice the irony.

I also suspect that it’s harder for some white people from privileged backgrounds to wrap their heads around Kendrick than it would be for them to wrap their heads around, say, Dr. Octagon. (Lamar is) dealing with topics they don’t necessarily want to look at, in a way that’s simultaneously unflinchingly direct and also very complex and layered. And the thing I want to say to the people who are dismissing his work today is: You can’t learn from a piece of music unless you spend some time exploring it on its own terms. If you don’t know its reference points, do your research. These composers position themselves as “serious” listeners. Why not act like it?

Q: Is there classical or new-music work that you see as addressing some of those same themes? How are those works received by other performers and composers?

A: A classical work about the experience of growing up in the midst of gang feuds and under the thumb of systemic racism, and what that does to a person? There probably is, but I haven’t heard it.

Q: I imagine that says something about who gets access to classical-music education and training in the first place.

A: For sure. Speaking as a white person from a privileged background myself, (Lamar’s album) “good kid, m.A.A.d city” was very eye-opening for me. I remember listening to it at one point and thinking (as Ayesha A. Siddiqi tweeted a couple of years ago) “white people are afraid of a dystopian future, but the dystopia is already here.” I haven’t seen the new-music world dealing with that. Though there may be things I’ve missed.

Q: We’ve been talking a lot about simple, stereotypical contempt for hip-hop, which seems like an important factor in some of the reactions you’ve described, but not necessarily the only one. I was curious about something else you said in a Facebook post, which suggested that some folks in the classical and new-music worlds feel a lot of anxiety about whether their work is resonating and finding audiences. What role does the Pulitzer Prize play among classical and new-music artists today? Is it seen as important? Is it something to aspire to? A foothold that the form has in mainstream culture?

A: The contemporary classical world’s relationship with prizes is complicated. Plenty of people don’t care about the Pulitzer, and it’s been criticized as a way to give a “lifetime achievement award” to someone who really should have gotten it for a more important piece years ago. (See: both Ornette Coleman and Steve Reich.) That’s why the shift toward younger composers like Du Yun and Caroline Shaw in the last decade has sparked so much controversy. And that trend is also in play in the reaction to Kendrick Lamar’s win.

But there’s also the fact that, if you win the Pulitzer, commissions start flooding in. Your ability to get a university job skyrockets. I remember there was a faculty opening at Stanford last year, and someone on Facebook said wryly, “well, that’ll be a nice opportunity for someone on the Pulitzer shortlist.”

Q: And I would imagine those opportunities feel increasingly precious to people in more precarious arts environment.

A: Yes. Contemporary classical music rarely pays for itself, and arts funding is in a terrible state in this country. Which leads to the paradoxical result that while composers and performers in this genre largely come from privilege, many struggle to make ends meet.

Q: That makes a lot of sense, and I’m sure produces a lot of uncomfortable feelings – and possibly unattractive behavior – in general, not just in relation to the Pulitzer Prizes.

A: For sure. There’s a lot of fear of being eclipsed by pop, rock and hip-hop, both economically and culturally. Because we don’t want to admit that we’re working in a niche genre. Classical musicians have been holding up the notion of our work’s universality as an ideal for a long time. It was never really true, but it’s even less true now, and we as a subculture haven’t really reckoned with that.

Q: As fraught as the response to Lamar’s win seems to have been over the past couple of days, do you see any conversations starting to emerge out of it? Are there lessons you think the naysayers in your professional communities could learn from this? Or does it draw attention to issues, like limited opportunities and downward economic mobility in the field, that no one prize was ever going to fix for everyone?

A: There have been some productive conversations, yeah. There’s an excellent Facebook post by Kate Wagner that’s being shared, where she talks about how if we’re concerned about new music falling by the wayside, we should be worrying more about student loans, unpaid labor, exorbitant application fees and the disappearance of tenure-track jobs, and less about something as elusive and limited as the Pulitzer.

I’ve also seen some people argue that it would be better for the Pulitzer to go to classical composers from underrepresented groups than to Kendrick Lamar. I think it’s worth noting that I’ve only heard white people say this. The composers of color I know have been very positive about “DAMN.” winning the prize. Including last year’s winner, Du Yun.

But I feel like we’re never going to have a really honest conversation about this until we can talk about our underlying fear of cultural irrelevance. And to talk about that, we need to ask who specifically we want to be relevant to.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.