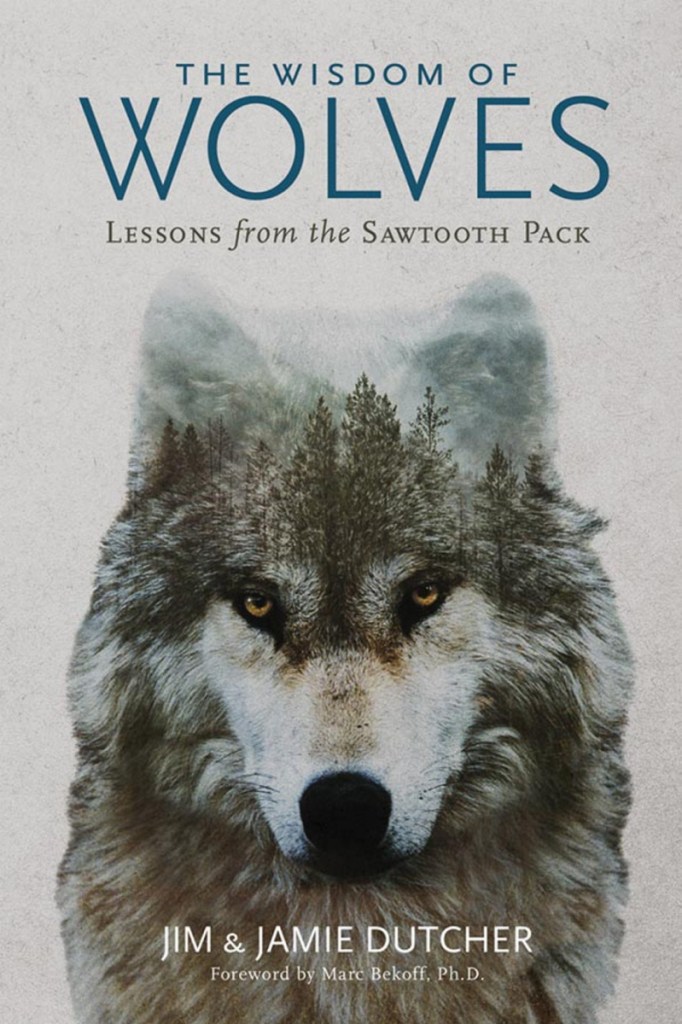

For six years in the 1990s, documentary filmmaker Jim Dutcher lived among a pack of wolves in Idaho. His wife, Jamie, joined him in 1993, and together they witnessed acts of wolf devotion, compassion and rivalry. The Dutchers have documented the sights and sounds of their pack mates, producing six books and three television documentaries. Now, writing in alternate chapters in “The Wisdom of Wolves,” Jim and Jamie look back on their experiences and make a heartfelt plea for smarter and kinder treatment of these majestic animals.

It’s not mere anthropomorphism to say that the wolves were smart and kind. “Caring for the young ones – and for each other – was the central mission in their lives,” the Dutchers explain. The alpha leader, whom they named Kamots, grasped the perspective of other wolves in the pack and often sought to reassure them. When he let his low-ranking brother, Lakota, win a game of tag, he demonstrated an understanding that “it would be rewarding for Lakota to enjoy a moment of victory.” Anecdotes such as these suggest that this capacity for a theory of mind – seeing the world from another’s perspective – is found in wolves generally.

Occasionally, the Dutchers’ interpretation of wolf behavior oversteps the bounds of science. How could they know, for instance, that the wolves had “anticipated” the birth of pups to a pregnant female? And wolves can’t correctly be said to “organize themselves similarly to the way early human societies did: as nuclear families within extended families,” because no solid evidence of the family arrangements of our early ancestors exists.

But these are minor objections to a work that is illuminating in its mission to tell the story of the wolf mind and of individual wolf personalities. These animals aren’t vicious predators who seek out livestock to kill. It’s our own thirst for killing wolves that disrupts their culture by fragmenting families and causing the loss of elder wolves’ knowledge. It is our own violence that pushes the survivors to venture unpredictably toward ranches and other settlements. In this way, “we willfully continue to undermine the very thing that could make coexistence between our two species possible”: allowing wild-wolf cultures to remain intact.

In an irony they are the first to acknowledge, the Dutchers themselves never lived with wild wolves. In 1990, Jim constructed a 25-acre enclosure on Forest Service land. He then set about creating a wolf pack by hand – rearing pups and introducing different generations to make a family of 11. Jim and Jamie lived and slept in an enclave within the enclosure.

As the Dutchers see it, these wolves – the Sawtooth Pack – became their “social partners.” When the first wolf pups in 50 years in the entire Sawtooth, Idaho, region were born to a female in the Dutchers’ pack, she coolly allowed Jamie to enter the birthing den. It was a marvel of a place that the wolf herself constructed, with a six-foot-long entryway and a chamber featuring a shelf carved out where the pups could safely be stowed.

In instigating interactions such as these, the Dutchers asked the wolves to be “ambassadors for their kind.” The pack, they conclude, “rose to this challenge with more grace than we could have hoped for.”

After six years, the permits to keep the wolves on the Forest Service land were denied, an outcome the Dutchers had anticipated and prepared for. In 1996, the wolves were sedated then relocated to Nez Percé tribal lands in northern Idaho, a process that the Dutchers refer to as “probably the most stressful event of these wolves’ lives.” This makes me wonder: lacking choice in what happened to them, are the wolves accurately described as the Dutchers’ “social partners?”

Yet it’s an inescapable and sorrowful fact that these wolves would almost certainly have been under greater duress had they lived fully wild. In Idaho, no region is protected for wolves. In 2014, the Dutchers report, the state’s department of fish and game sold 43,300 hunting tags, though only 650 wolves were living in the state.

Jim and Jamie Dutcher provide a beautiful portrait of these highly misunderstood animals. Wolves, they tell us, live with “an openness and a sincerity that are beyond most humans.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.