John Moore lives and paints in the midcoast town of Belfast. For much of his career, Moore, born in 1941, has been an educator. In 2009, he retired as chair of the department of fine arts at the University of Pennsylvania. Moore has also had dozens of solo exhibitions, although “Resonance,” now on view at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, is his first solo show at a Maine museum.

Moore’s works generally feature industrial interior spaces with views through windows and a few modes of quirky landscapes. They immediately and unapologetically present themselves as odd.

The images have a hallucinatory or dreamlike sense. They are precise to the point of engineered, but they exude an irrational quality that makes them undeniably otherworldly. At a glance, “Sunday Morning Sunlight,” for example, could hardly be more prosaic. It’s a view through a pair of rooms in an old factory building to a window. The old space is richly textured by bricks and colorful layers of peeling paint. A sliver of sunlight slashed into just a few rectangular dots reaches from the open window to welcome our gaze and pull us visually through the space. It’s painted in an impressively competent photorealist style, and our inclination is to read the image as real and patiently observed. Moore is a master, after all, of textures and light. But something else is going on, and it’s uncanny to the point of unnerving. There is no distortion in the architectural lines, something we particularly expect with photorealism: Single-point perspective, after all, is a world in which there are only two straight lines (the x and y axis) and otherwise is a world of curves, the reality of true perspective. Moreover, the image in the window is hauntingly familiar. Indeed, it is the same window image from “Pearl,” in which it plays a similar role behind a (more obviously) flattened grid. By the time we get to “Sunday Morning,” the window scene arrives as a memory, like a dream fragment. This shatters any belief we might have had that the scene was literal; Moore is up to something quite different from the straightforward rendering of reality.

“Sunday Morning Sunlight,” 2017, oil on canvas, 70 by 60 inches.

Photorealism has become our understanding of “realism.” But, frankly speaking, it is a basic literalist approach that can be learned by anyone. The artist who deserves the most credit for changing the culture of realism to this mode is fellow Mainer Richard Estes. But this is not what Estes actually does with his own paintings. To be sure, he uses photorealist effects, but Estes uses multiple perspectives and sets the issue of transitioning between the different perspectives as his painterly problem, and that is where his true artistry lies. Moore does something similar, but in the opposite direction. Moore takes what we know – for example, that a window of glass blocks is a actually linear grid of straight lines – and then sets to accommodating his flat grids to the photorealist effects of the scene before him. It’s like Estes inverted.

Moore elegantly presents this in his artist statement with a quote by poet Wallace Stevens, who referred to “the incessant conjunction between things as they are and things imagined.” We know the window is a grid, so while Moore is not wrong to portray it that way, we don’t see things that way. The camera, like our eye, distorts this physical fact: Things farther away, for example, are smaller. Moore’s tension is between how things are and how they appear to the eye.

“River Drivers,” 2017, oil on canvas, 46 by 46 inches.

This puts Moore in company with early Renaissance painters, such as Paolo Uccello, who struggled to accommodate what they knew with what they observed (as well as the stylistic expectations of the day), especially since single-point perspective as a comprehensive system for pictures wasn’t invented until the early 1400s. It also puts Moore in the company of modernist and contemporary painters focused on the system logic of paintings. Moore’s work reminds me most of Gregory Gillespie (1936-2000), whose switching between these systems gave his paintings an intense hallucinatory quality.

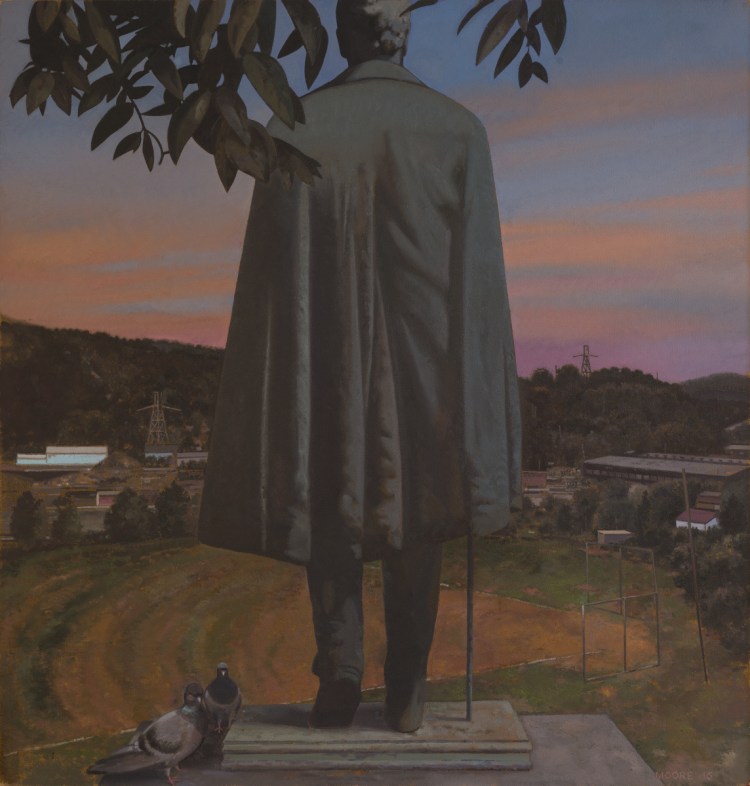

Uccello particularly comes to mind when considering “Harmony Place” and “River Drivers,” two images that include cast-metal figurative sculptures. (Uccello was famous for his gridded battle scenes, for example, but also for his painting of a sculpture of John Hawkwood in the Duomo in Florence.) Moore’s sculpted (presumably bronze) figures are monochrome, so they appear as a different (and artistically created) system within the natural world of color. We see the two heroically scaled laborers in “River Drivers” on a plinth in front of a building under a sunset sky. The plinth and building are flattened to the point of isometric drawing – the measurable style of engineering. The figures are fully modeled in the sense of volume. Ironically enough, the Maxfield Parrish-like colorful sky then becomes the “flat” background. A coin-like moon wittily looks on from the upper left. On the right, a telephone pole, again rendered with straight lines, tilts in, a hilariously brilliant bit of camouflage. In “Harmony Place,” we stand behind the monochrome caped figure, surveying the colorful landscape from his perspective. Guiding us in is a pair of pigeons at his feet, with one directly facing us; it’s a Renaissance gimmick, and so here it works as a particularly playful gesture.

“Turnstile,” 2012, oil on canvas, 70 by 68 inches.

“Turnstile” is Moore’s most complete painting. We see a modernist building at sunset through a scratched up and textured full-body double turnstile with its dozens of almost-interlocking prongs. The cylindrical turnstile, however, plays more the part of the flat grid, an impassable fence. We can only move past it visually. Under a sky that shifts from crepuscular pink to the soft greens and blues of sunset is a 1960s building with an upward-tilted “V” roof. In its windows, we see reflected (behind us) a day-blue sky, impossible, of course, if our eyes are pointed towards the setting sun.

Moore’s more straightforward landscapes are each driven by the irrational intersection of incompatible systems. Above and below a fence line are two different perspectives. Colored leaves stand up on the surface of a painting of a nicely placed pond. Trees block our entering spaces, and what seem the most accessible of Moore’s works become the most impossible for us to visit or see. These last pieces can be claustrophobic, but their power, however uncomfortable, is undeniable.

Among the irrational aspects of memory, imagination, dreamscapes and divergent painterly systems, Moore looks again and again to the fundamental modernist trope of the grid. The grid’s appeal to modernist painters was its radical and measurable (i.e. isometric) literalism. For modernists (like Mondrian, Ad Reinhardt and a million others), the grid mapped not the visual space of painting but the actual painting surface itself.

Moore can be seen as mobilizing the grid to take on photorealist space, setting up a sort of showdown between modernism and post-modernism. While his works are dense and intense, it is this sense of struggle that defines them and makes them exciting. They are not narratives that resolve – quite the opposite. The longer you look, the more the compatibility battle intensifies. They are odd, uncanny and often irrationally uncomfortable, but they forcefully announce Moore as a master of photosurrealism.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.