The Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockland is now presenting a trio of highly charged exhibitions. The entrance and main gallery feature “American Steel,” an installation of works made from nails by John Bisbee. This is joined by Tom Burckhardt’s politically poignant cardboard and paint consideration of a world turned upside down (in a flood no less) and Jocelyn Lee’s “The Appearance of Things,” a deep ranging photographic meditation on female and natural forms.

Bisbee uses the front entrance wall of CMCA to mount a statement in his impressively designed nail script. The words – like all of his work – are actually made of nails:

“WE TRUMPET THE COMMON NAIL / THE OVERLOOKED LITTLE PRICK / THAT HOLDS THE WHOLE THING TOGETHER / THEIR HEADS GET BENT / POUNDED BY EVERY PENNY / ALTHOUGH THEY GET SCREWED / THEY ALWAYS STAY SHARP AND BRIGHT”

– JOHN BISBEE

Sitting nearby is an ear trumpet (yup, “TRUMPET”) sculpted in nails, a smaller version of the excellent work acquired by the Portland Museum of Art from one of its biennials. While the show is billed as Bisbee stepping from decorative abstraction (always with his nails) towards political discourse, this passage riddled with phallic references is a disappointing mash of frat-boy humor. It’s hardly the way to set a stage.

Bisbee’s next work might be his strongest. It’s a map of America made from medallions that seem to be floating away from the solid mass. While the direction might not be obvious, the placement of several on the floor makes the case clear.

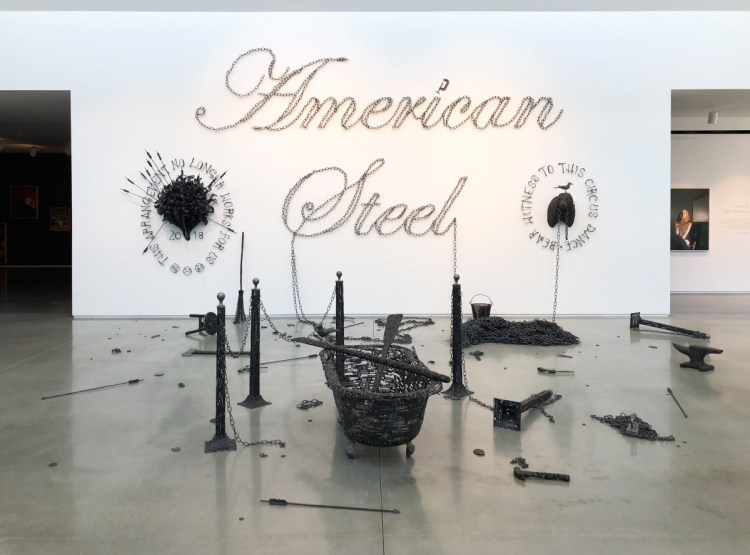

Bisbee’s installation in the CMCA’s main gallery is certainly an impressive sight. In the far corner is a huge sculptural installation with the words “DON’T BET ON ME” (a play on the Gadsden flag with “tread” switched out for “bet”), a wall covered in lengths of barbed wire that (from the other side of the room) reads: “DREAM ON,” a suitcase with a bird on it in behind two unconnected stanchions and an installation mainly of swords, guns, arrows and stanchions with looping chain rodeo lasso script reading “American Steel.”

In terms of content, “American Steel” is a misfire. We can assume from the “common nail” statement that Bisbee wants to speak to the everyman, but he sets up his content to be seen as a quick joke, and where there is the possibility for depth, he doesn’t lead us down the path. The Gadsden flag piece, for example, includes a giant snake, but it seems more like a dead pile of snake surrounded by elegant tubes (maybe molted skin, or a play on Ben Franklin’s 1854 “Join, or Die” image of the eight colonies divided that became the standard image for the American Revolution). Black spikes shoot off the wall from the words, giving the whole thing a comic book-like energy and feel.

John Bisbee’s “American Steel,” 2018, forged and welded nails.

The “Dream On” work also floats in no-man’s land. To begin, the phrase clearly hails the 1973 Aerosmith song (and Bisbee is an accomplished musician), which, in turn, calls to mind the band “American Steel” rather than, say, the company in Portland, American Steel & Aluminum, which is, I believe, the only metals distributor in the state. (But would an everyman piece go there or with the popular song?). The barbed wire,however, is widely regarded as an American invention of the 1860s – cheap and effective fencing that was easy to manufacture and transport – that allowed for easier commercial development of the West. There’s an interesting story there, but it seems to short-circuit with Bisbee’s stated political position.

The “American Steel” installation plays to the violence of the settling of the West, complete with a cowboys-and-Indians theme among Bisbee’s (impressively crafted) arrows and six-shooters and varied objects: a pile of chain, an anvil, a clawfoot tub replete with oars, etc.

Considering the material elegance of Bisbee’s usual fine craft abstraction, his first-time foray into conceptual discourse (with the groaner penis jokes, however, it’s hard to even call it that) is deeply disappointing. In terms of energy and skill, it’s still an entertaining exhibition, but its failure is all the more apparent because it is presented alongside two shows that, in fact, dig deeply and intelligently into conceptual content.

TOM BURCKHARDT’S “Studio Flood” is a fun, smart and effective meditation on a world turned upside down. It’s a life-size painting studio rendered in cardboard and black paint. Burckhardt doesn’t skimp on the details, the narrative or his perspective as a Trump-despising environmentalist (there are posters, magazines, and plenty of popular culture clues). The studio ceiling is our floor, but the floor isn’t quite our ceiling – because the studio is flooded. And that is a very odd thing considering the water and the stuff floating in it are above our heads. Moreover, the views outside the windows (super fun dioramas with lights) show a flooded world, but it’s right-side up. So are we upside down, or what? This opens the doors (or should we call them floodgates) to metaphor, dreams and so on.

View of Tom Burckhardt’s “Studio Flood,” 2016-2018, paint and cardboard

The idea behind installment directly relates to a song tethered to the American Revolution: The 1640 tune “The World Turned Upside Down” was allegedly played by the British at the 1781 surrender at Yorktown. (While that used to be a bit of arcane lore, in the wake of “Hamilton” it’s probably now known by half the country.)

While “Studio Flood” is eminently amusing, fun and witty, Burckhardt’s disaster dream goes deep regarding ideas about personal fear, First Amendment concerns, American politics, climate change, disaster and far more. It also brings to mind other art, for example, the brilliant and heart-wrenching work of University of Maine at Augusta professor Peter Precourt, whose illustrated-novel-style paintings of the “Katrina Chronicles” actually tell the story of his losing his entire life’s artwork when his studio was destroyed by the hurricane-related flooding.

JOCELYN LEE’S “The Appearance of Things” is an ambitious and beautiful exhibition of large-scale photography, mostly of female nudes near or in water and still lifes shot in water. The curatorial and conceptual content of the installation are easy to follow: Lee connects adjacent work by color, form and idea. The long auburn hair of a model, for example, immediately looks to the auburn-green seaweed in a nearby image. A larger than average woman floats in water while next to her we see well past ripe apples and fruit floating in an even more lavishly printed image. Lee finds beauty particularly well with older models. And while she sometimes misses with her larger models, the overall effect of the show is beautiful and deeply respectful. “The Perfect Breast,” for example, features a nude in the forest, her feet deep in the moss, and we imagine her right breast was taken by mastectomy. “Milk and Sap” has a mother breastfeeding her baby in a forest, her feet similarly hidden, and she has milk running down her right side. The light in these two images is gorgeous.

“Dark Matter #5 (Sunflower and Sky),” 2017, archival pigment print, 14 by 11 inches.

While they wouldn’t have the same impact or power without the accompanying figurative images, Lee’s images of fruit floating in water are particularly notable. In her “Dark Matter #5,” for example, she presents what looks like a decrepit sunflower floating with a few berry-like fruits. We see the growth down in the (ocean) water and the sky reflected above. In terms of color, light, texture and aesthetic balance, it is a complex and unexpectedly satisfying image.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.