If the resistance to President Trump’s climate policies needed a standard bearer, California would be it. Here’s a state that requires all new homes to have solar power, puts a price on carbon emissions and forces automakers to make more zero-emission vehicles.

And now? California, which is hosting a climate summit this week, has a new law to make the state’s electricity grid 100 percent carbon free by 2045 – using wind, solar, geothermal and hydropower.

It’s a trend. Across the country over 70 cities, five counties and one state – from Spokane, Wash. to Denver, from Minneapolis to New Brunswick, New Jersey – are looking to turn their electricity grids entirely “green.”

“By setting a real marker we’re sending a message to the country and world that regardless of who occupies the White House today, with or without Washington, California is moving forward,” said Kevin de León, D, a California state senator who sponsored the measure and who is running to oust Sen. Diane Feinstein, D-Calif.

The task, however, is a tall one. Scale is one reason; California is the world’s fifth largest economy. Its population will grow by several million over the next 27 years and the size of the economy will more than double, straining the electricity grid. Waves of electric vehicles, if they catch on, could also add to electricity demand.

Then there are the technological obstacles. Storage needs – and costs – spike higher as the use of renewable sources rises, eventually more than doubling the cost of new wind or solar.

Even if California and its followers all hit their targets, the impact could be modest. The United Nations Environment Programme, the definitive source for tracking the so-called “emissions gap” between what the world aspires to do about climate change and what it’s actually doing, estimates that “sub-national” actors would reduce emissions by about one or two percentage points of the global total by 2030.

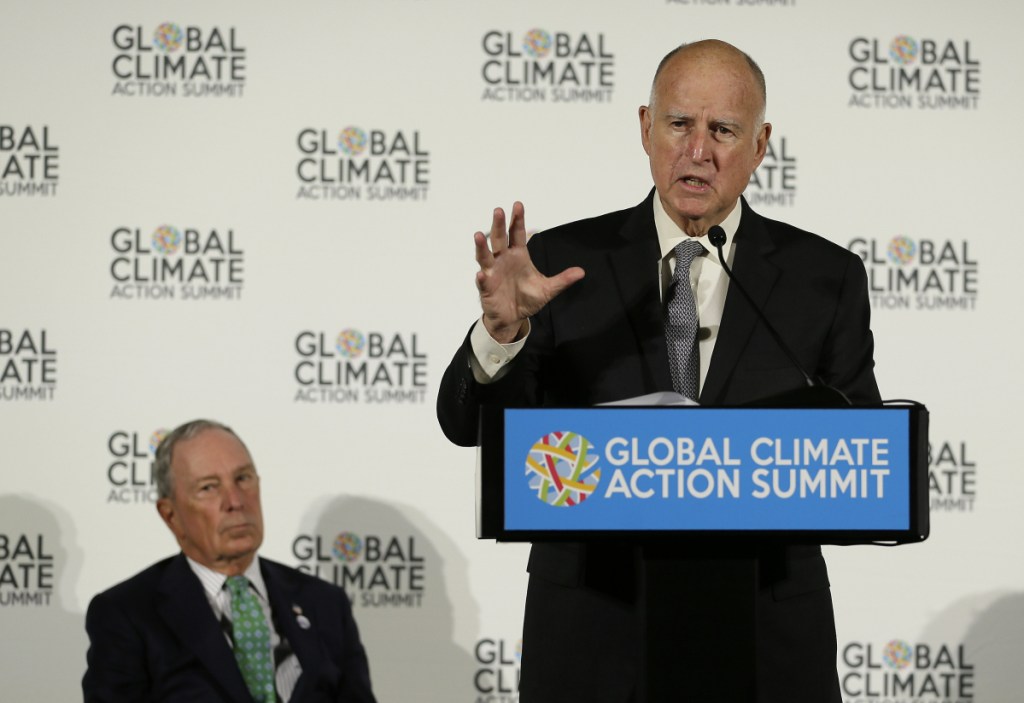

Like so many other Silicon Valley types, Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown, who signed the bill into law this week, is betting on innovation. He hopes the new measure spurs companies to develop batteries big and cheap enough to store intermittent renewable energy that is produced only when the sun shines or the wind blows – not necessary when it’s actually needed.

“This takes expert engineering, scientific research, political collaboration and great wisdom to forge ahead not in one administration but in several,” Brown said. “That’s why I say we’re like at the base camp. I’m looking up at Mount Everest. We’ve got a big mountain to climb.”

California, which still relies on natural gas for about a third of electricity generation, has some home advantages in chasing the 100 percent goal. It has large amounts of hydro and geothermal power. Moreover, electricity generation accounts for less than 20 percent of the state’s carbon emissions, far below the 34 percent level nationwide, according to the Energy Information Administration. Much of that is thanks to California’s moderate weather and modest amounts of heavy industry.

But the state’s war on climate change also deserves some credit. California set its first renewable goals in 2002. It has raised those targets four times. It also has a cap and trade system that limits carbon emissions while allowing companies to buy and sell credits to meet the targets. The current price is $15 a ton.

The state’s policies have attracted significant investments. The nonprofit research organization Next 10, founded by venture capitalist Noel Perry, said that 57.2 percent, or $1.4 billion, of all U.S. clean energy technology investment in 2017 went to California companies.

Brown has his worries though. The boom in solar has already swamped midday demand, once a troublesome peak time for electricity grids. Now, there’s so much solar some of it can’t be used. At times, grid operators are actually paying people to use solar.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story