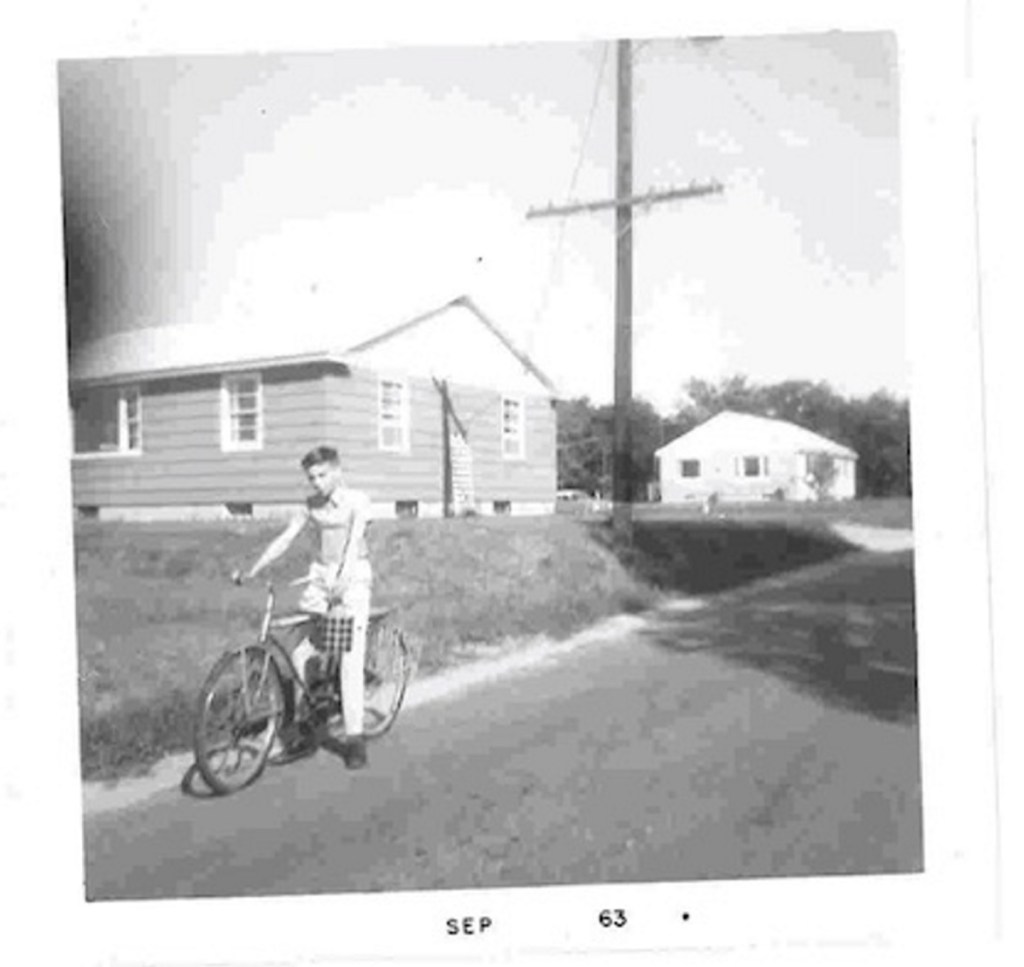

In the early 1960s, I was a scrawny teenager looking to drink in all I could to make the leap from small-town elementary school to small-town high school in an adjoining town. My father had a new, very small construction company, he having made his own leap from carpenter in the employ of a contractor to going it on his own. His capitalization was his hand tools, his rolling stock was a pickup truck. His first “employee” was me. No corporate structures, no credit lines (what was a “credit line,” anyway?). But he was an incredibly hard worker and had made a good name for himself. The American Dream awaited.

The big break came out of the blue. I learned of it by listening in on a conversation between him and my mother:

“I met a guy today who wants to redo Camp Ha-Wa-Ya (a residential camp for boys in my hometown of Harrison),” said my father with a rare level of excitement in his voice.

“Who is this guy?” asked my mother with a perceptible trace of skepticism.

“I didn’t get his name, but he’s a big deal in from New York and he’s the new owner of the camp. Wants to rebuild the whole camp and wants me to do it for time and materials until we’re far enough into it to go to proposals. He’s stopping in this week to meet me at the camp and go over the schedule.”

This arrangement held the promise of steady, long-term work, which is the holy grail for contractors. It also delivered a sense of promise that the market was going to support my father’s leap to independent contractor.

We arrived at the camp a bit early for the meeting. “Our” new customer was a solid 30 minutes late, the longest 30 minutes of my 13-year-old life. But it was worth the wait. The Cadillac with the New York plates slid into the parking lot and out jumped a character who was a Central Casting version of a big shot – fancy clothes, shiny shoes and lots of what we now refer to as “bling.”

The conversation which followed was lacking in coherent details. His description focused mainly on an immediate start, and the need for future, extensive work. The lack of detail was trumped by the size of the check he waved about. Handshakes were exchanged all around and his departure was as grand and abrupt as his arrival.

My father tore into the planning, hired a couple of carpenters and placed a sizable order for materials from the lumberyard. Our ship had come in.

The dream evaporated almost as quickly as it arrived. The lumberyard called to say our check had bounced. The police arrived seeking statements from my father regarding his dealings with Mr. Big Shot, adding that the man matched the description of someone on a tour of New England, passing bad checks as he went. They added it was unlikely that we would recover anything.

Maine being Maine, our recovery was not a financial trauma. The lumberyard took back the unused materials with no return charges. My father scraped up the money to pay the new hires for the limited time they were on our payroll. The primary hit was to my father’s reputation for doing things right and being entirely reliable. When I worked up the courage to question what we were going to do about this, the only answer he ever related was “we’re going to let it lie.” Mr. BS was never heard from again.

My father’s business went on to succeed, but he was never able to forgive himself. The collapse of the deal was the death knell for my new bike, but I came to understand that kicking over the traces often perpetuates the pain of mistakes made. A new bike eventually arrived via other work, and I had learned a lesson much more valuable than the bragging rights of new wheels. That account ended squared up.

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.