His death was announced by Andy Brack, a family spokesman. Complete details were not immediately available.

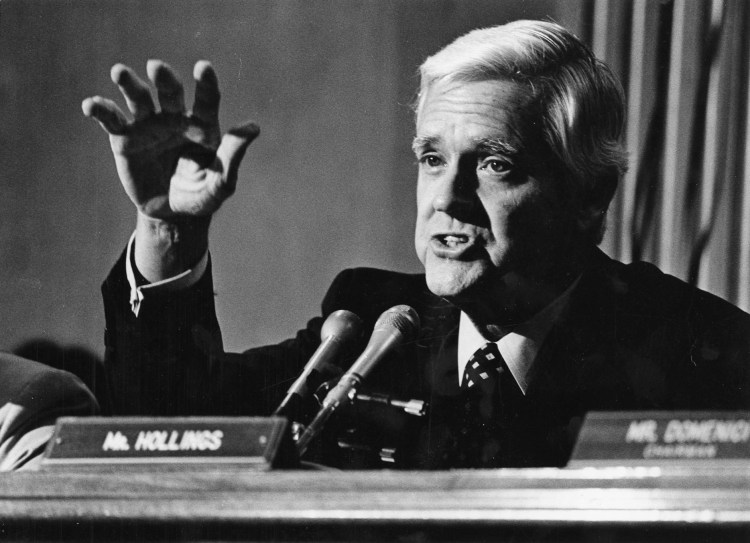

The silver-haired Senate stalwart, a Citadel graduate and World War II veteran, was perhaps best known as an author of the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Balanced Budget Act of 1985, a noteworthy effort by Congress to compel federal budget reductions.

He served in the Senate from 1966 to 2005 and was instrumental in enacting laws to alleviate childhood hunger, increase vehicle efficiency after the Arab oil embargo, and expand competition in telecommunications when the Internet was in its infancy.

He also drew attention for the unpredictable candor with which he expressed himself in his deep Southern drawl. His Charleston accent was so thick that Sen. Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, a close friend and fellow Democrat, once jovially introduced him as the first non-English-speaking candidate for president.

Hollings sought his party’s presidential nomination in 1984 but failed to garner much support with his “take your fiscal medicine” message. He dropped out of the race after finishing sixth in the New Hampshire primary, behind Sen. Gary Hart of Colorado, former Vice President Walter Mondale, Sen. John Glenn of Ohio, Jesse Jackson and former Sen. George McGovern of South Dakota.

Hollings was openly contemptuous of some of his former opponents. He ridiculed Mondale as a “lap dog” who would “lick the hand of everyone in sight.” He dismissed Glenn, a former astronaut and the first American to orbit the Earth, as a “Sky King . . . confused in his capsule.”

He also saved a barb for himself.

“I will never forget politicking for president,” he said. “I went to Worcester, Massachusetts. I knocked on the door, and the lady said, ‘Who are you?’ I said, ‘Fritz Hollings.’ She thought it was a German trucking company.”

Hollings had the distinction of being the longest-serving junior U.S. senator in history on Capitol Hill, where he was outranked for much of his tenure by Strom Thurmond, a wily political survivor who transitioned during his lengthy career from an anti-integration Democrat to a Republican.

The two South Carolinians took drastically different approaches to their jobs in the Senate, said Hastings Wyman Jr., founding editor of the Southern Political Report. “Thurmond, who wanted to push the South into the Republican column, painted with a broad brush and wasn’t terribly interested in lawmaking,” he said. “Hollings was a much more pragmatic legislator who cared about details and programs.”

Like Thurmond, Hollings began his career in an Old South dominated by the Democratic Party and ended it in a New South decidedly partial to Republicans. He gradually moved to the center, walking an occasionally treacherous path between political accommodation and principle.

As governor from 1959 to 1963, he was determined to prevent an outbreak of violence over public school integration mandated by the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Although he opposed integration at the time, Hollings, unlike many other Southern governors, achieved a peaceful transition.

In the Senate, Hollings continued his journey away from the politics of Jim Crow. In 1967, he voted against the U.S. Supreme Court nomination of Thurgood Marshall, who became the court’s first black justice, but he later explained, “It was politics, not racism.” In 1991, he supported the nomination of another African American – Clarence Thomas – to the high court. In the meantime, he became generally supportive of civil rights legislation.

Winning term after term, Hollings became chairman of the Budget Committee, chairman of the Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee, and a senior member of the powerful Committee on Appropriations.

He used his clout and legislative prowess to build personal alliances, defend South Carolina’s diminishing textile industry and bring new industries to the state. He insisted that his opposition to free-trade pacts was not protectionism for the South’s textile industry but rather an effort to prevent jobs from going overseas.

As his profile rose, his abrasive remarks drew increasingly intense criticism in the national media.

Amid a trade dispute with Japan in 1992, Hollings told a gathering of workers in Hartsville, South Carolina, that they “should draw a mushroom cloud and put underneath it: ‘Made in America by lazy and illiterate workers and tested in Japan.’ ” The senator was alluding to the atomic bombs that the United States dropped on Japan to end World War II.

When pressured to apologize, he replied, “I’m not Japan-bashing. I’m defending against America-bashing.”

During a debate over school prayer in 1981, he labeled his Jewish colleague Howard Metzenbaum, D-Ohio, “the senator from B’nai Brith,” referring to the Jewish service organization. Hollings later apologized and said he meant his comments “only in fun.”

In 1993, the NAACP lambasted him for saying of African delegates at an international trade conference in Switzerland that, “rather than eating each other, they’d just come up and get a good square meal in Geneva.” Hollings insisted that he was joking. Years earlier, he called civil rights leader Jesse Jackson’s National Rainbow Coalition “the blackbow coalition.”

Hollings’ off-the-cuff remarks, while polarizing, appealed to many voters who saw him as a fearless spokesman in an era of stifling political correctness.

David Rudd, a Washington lobbyist and former chief of staff to Hollings, once told the State newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, “People in this country are so starved for anything resembling emotional honesty from their elected officials, they will reward them even if they don’t agree with them.”

Ernest Frederick Hollings was born Jan. 1, 1922, in Charleston, where his family owned a paper mill. After graduating in 1942 from The Citadel, a military college in Charleston, he served as an Army artillery officer during World War II, taking part in five battle campaigns, from North Africa to Central Europe. His decorations included the Bronze Star Medal.

Hollings received a law degree from the University of South Carolina in 1947 and served in the South Carolina House of Representatives before he was elected lieutenant governor in 1954. He was elected governor in 1958, at 36.

The jovial, impeccably tailored Hollings was a frequent traveler to Wall Street, Latin America and Europe, where he pitched investment in a nonunion state with a triple-A credit rating. In one marathon week in New York, he signed up 63 companies – including 17 at one lunch – to open plants in his home state.

One major political test involved the desegregation of public education in South Carolina. Throughout his early political career, Hollings had opposed integration of the state’s public schools. But he had also taken strong positions against racial violence, and before leaving office in 1963 he was ready to concede that resistance to school integration was a lost cause. In his last address to the state’s General Assembly, he implored legislators to allow South Carolina schools to be integrated peacefully.

“We of today must realize the lesson of 100 years ago and move on for the good of South Carolina and our United States,” he said, alluding to the Civil War. “This should be done with dignity. It must be done with law and order.”

Political advisers urged Hollings to avoid becoming involved in the case of Harvey Gantt, a black student who transferred to all-white Clemson University in 1963. Hollings sent word to U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy that the state would keep order and wanted no federal marshals or troops dispatched to South Carolina.

Gantt, who years later became the first black mayor of Charlotte, North Carolina, and a Democratic Party power broker, registered at Clemson with no picketing or jeering soon after Hollings stepped down as governor.

Hollings’ traditionally Southern views were shaken by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” according to David R. Goldfield’s “Black, White, and Southern” (1991), a study of race relations in the South. In Goldfield’s book, Hollings described his response to King’s writings:

“[A]s governor, for four years I enforced those Jim Crow laws. I did not understand, I did not appreciate what King had in mind . . . until he wrote that letter. He opened my eyes and he set me free.”

Hollings’ first attempt to win election to the U.S. Senate failed in 1962, when he tried to unseat Olin D. Johnston, an old-style Southern populist, in the Democratic primary. After Johnston died in 1965, Hollings filled out the remaining two years of his term. He won a full term in 1968 and was reelected five times.

His early years in the Senate were marked by a high-profile war on hunger in South Carolina. His efforts includeda book called “The Case Against Hunger” (1970). He encouraged the expansion of the federal food stamp program and helped sponsor legislation that established the Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants and Children, commonly known as WIC.

He spoke poignantly about his change of heart on the issue of hunger. “What I found was not a bunch of lazy oafs who didn’t want to work, as I had been led to believe,” he told The Washington Post, “but elderly people and little children and people too sick to work.”

Hollings was also considered a legislative father of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which was established in 1970. For years, he worked on conservation and preservation efforts to protect coastal and marine life.

He became perhaps best known as a co-author – with Sens. Phil Gramm, R-Texas, and Warren Rudman, R-N.H. – of the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings act, which called for a balanced federal budget within six years. Among other measures, the legislation introduced automatic cuts, called sequestrations, to be applied if spending limits were not met.

Ultimately, conservatives and liberals failed to agree on ways to achieve substantial spending cuts, a key provision was ruled unconstitutional and the law was overtaken by other legislation. But it was credited with curbing deficit growth for a period.

His first marriage, to Patricia Salley, ended in divorce. He subsequently was married to Rita “Peatsy” Liddy from 1971 until her death in 2012. Survivors include three children from his first marriage, Michael Hollings and Ernest F. “Fritzie” Hollings III and Helen Hayne Reardon; and several grandchildren. A daughter, Salley Hollings, died in 2003.

After Thurmond’s death in 2003 at 100, Hollings became South Carolina’s senior senator. He soon announced his decision to retire from public life and did not seek re-elelction in 2004.

Asked by the Post and Courier newspaper in Charleston about what he might like for a gravestone epitaph, he suggested “something like that letter that y’all put in as a letter to the editor: ‘We hope Hollings enjoys his retirement because we sure as hell will.’ ”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.