The most notorious fake letter in American politics entered the history books on a snowy New Hampshire day in 1972.

Published by the arch-conservative Manchester Union Leader less than two weeks before the New Hampshire primary, the letter alleged that Sen. Edmund Muskie, D-Maine, then the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination to run against President Richard Nixon, had condoned and laughed about use of the derogatory term “Canuck” to describe French-speaking Canadians. Muskie responded to the “Canuck letter” with a display of anger that undermined – and he thought ultimately doomed – his bid for the presidency.

It turned out, however, that he had good reason to be outraged. Before the year was out, The Washington Post revealed that the letter was penned as part of a dirty-tricks campaign. It was organized not by Russian operatives but by Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President and included the bugging of Democratic national headquarters at the Watergate apartment complex.

Mailed with a Deerfield Beach, Florida, postmark and written in a childish hand, the letter claimed that an aide made a disparaging reference to “Cannocks” within earshot of Muskie when the candidate appeared at a local drug-treatment center. When the letter writer, who identified himself as Paul Morrison, asked for an explanation of the term, Muskie supposedly laughed and answered: “Come to New England and see.”

“We have always known that Sen. Muskie was a hypocrite,” the Union Leader declared in an accompanying editorial, “but we never expected to have it so clearly revealed.”

The allegation, if true, was potentially explosive. New Hampshire included a large Francophone population whose support would be vital if Muskie hoped to get more than 50 percent of the vote in the March 7 primary to fend off an energetic challenge from Sen. George McGovern, D-S.D. Muskie advisers thought the prominent display of the Canuck letter in the Union Leader threatened their candidate’s chances of reaching that goal, according to James M. Naughton in the New York Times.

Phony missives have been a staple of American political skulduggery since the days of George Washington. But none had the immediate, incendiary effect of the Canuck letter.

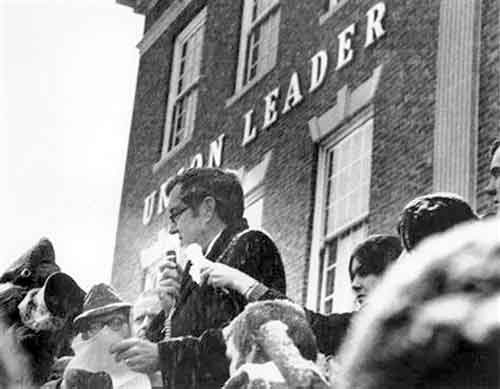

On Feb. 26, two days after the letter and editorial appeared, an enraged, bareheaded Muskie addressed a crowd of journalists and supporters outside the offices of the Union Leader. As the snow fell, he denounced William Loeb, the newspaper’s publisher, as a “gutless coward” for publishing the letter and a separate, unflattering item about Jane Muskie, the senator’s wife.

“That letter is a lie,” Muskie declared, Naughton reported in the Times.

As he stood outside the newspaper office, Muskie may have cried – The Washington Post’s David S. Broder reported that tears were “streaming down his face.” Naughton wrote that Muskie at one point “broke into tears,” while other accounts made no mention of crying by the candidate. In the years that followed, Muskie insisted he did not cry and that it was melting snow, not tears, that reporters saw on his face. Recounting the scene in the Washington Monthly 15 years later, Broder wrote “it is unclear whether Muskie did cry.”

While accounts differed about whether – or how copiously – Muskie wept, there was no doubt about his fury. “The 60 to 70 newsmen and supporters huddled in the snowstorm to hear the senator’s speech watched with surprise as the normally disciplined Muskie let his anger and his frustration show,” Broder wrote.

Questions about the authenticity of the letter emerged almost immediately. Although Loeb hinted to Broder that he had been in touch with its author, Broder reported that there was no Paul Morrison listed in the Deerfield Beach telephone book. Witnesses who were present with Muskie at the treatment center denied hearing anyone use the word “Canuck.” And Muskie, whose father was a Polish immigrant, said ethnic slurs of any kind were abhorrent to him.

Muskie was particularly indignant about the newspaper’s focus on his wife, Broder wrote.

“Muskie’s shoulder shook, and he rubbed his face hard. ‘A good woman …,’ he managed to say, and then the tears, mingled with the melting snow on his head, stopped him again. For 20 seconds, the crowd stood silent, as Muskie seemed unable to go on. At that point, Louis (Jalbert), an old friend from Maine, shouted out, ‘Who’s with Muskie?’ and the crowd cheered long enough for the senator to compose himself.”

The public display of anger came as a surprise to many who regarded the lanky Muskie, Hubert Humphrey’s vice-presidential running mate in 1968, as a voice of reason in the highly charged politics of the era. On the eve of the 1970 congressional elections, appearing after a taped speech by Nixon, Muskie delivered well-regarded remarks to a nationwide audience. While Nixon’s “extraordinarily poor telecast” showed the president “at his shrillest,” Muskie appeared “quiet” and “self-possessed,” according to presidential campaign historian Theodore White.

Muskie was often described as “Lincolnesque,” but the senator also had a temper. While campaigning in New Hampshire in early February, according to Broder, Muskie on several occasions angrily accused high school students of being McGovern provocateurs. Muskie loathed the media, and insiders on the Muskie campaign worried about his “tendency to emotional outburst,” White wrote.

The stakes were high for Muskie in New Hampshire. No one doubted he would win the primary – the question was, by how much?

“The accepted benchmarks are these: Muskie will be doing well if he gets the 65 percent of the Democratic vote he was credited with having in a January poll commissioned by the Boston Globe,” Broder wrote on Feb. 13. “He will be hurt if he slips below 50 percent and wins not by a majority but by a plurality.” Broder noted that New Hampshire college students had turned out in force to campaign for McGovern.

As the primary approached, signs of eroding support multiplied. On March 4, David Nyhan wrote in the Globe that Muskie’s campaign displayed “the weariness of the long-distance front runner” and that campaign aides were predicting their candidate would win with less than 50 percent of the vote. On March 5, the Globe published a poll showing Muskie’s support at 42 percent.

In the end, Muskie won the primary with 46 percent of the vote – better than the Globe’s poll but far below earlier projections. His campaign never recovered from its New Hampshire showing, and he withdrew from the race on April 27.

Muskie later blamed his outburst in Manchester on exhaustion caused by cross-country campaigning. But he acknowledged to White that the display of anger proved too much to overcome. “It changed people’s minds about me, of what kind of guy I was,” Muskie said. “They were looking for a strong, steady man, and here I was, weak.”

The Canuck letter receded from the headlines but returned in the fall as The Post’s investigation of the Watergate scandal picked up steam. On Oct. 10, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein reported that the Watergate bugging “stemmed from a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage” conducted by the Nixon campaign. “Law enforcement sources said that probably the best example of the sabotage” was the Canuck letter, the story said. But it was only the tip of the iceberg.

“During their Watergate investigation, federal agents established that hundreds of thousands of dollars in Nixon campaign contributions had been set aside to pay for an extensive undercover campaign aimed at discrediting individual Democratic presidential candidates and disrupting their campaigns,” the reporters wrote.

The story said White House aide Ken. W. Clawson admitted conversationally to Post reporter Marilyn Berger that he wrote the Canuck letter but subsequently denied doing so and claimed he had been misunderstood when asked about the conversation.

Muskie suspected his White House bid had been targeted. “Our campaign was constantly plagued by leaks and disruptions and fabrications,” the senator said in an interview The Post published Oct. 13, “but we could never pinpoint who was doing it.” He said he assumed the Nixon campaign was behind the sabotage but offered no evidence to back up the claim, nor was he willing to assess the damage it caused.

But he was less reticent about the fake letter he denounced in Manchester. “The Canuck letter,” Muskie conceded, “definitely hurt us.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.