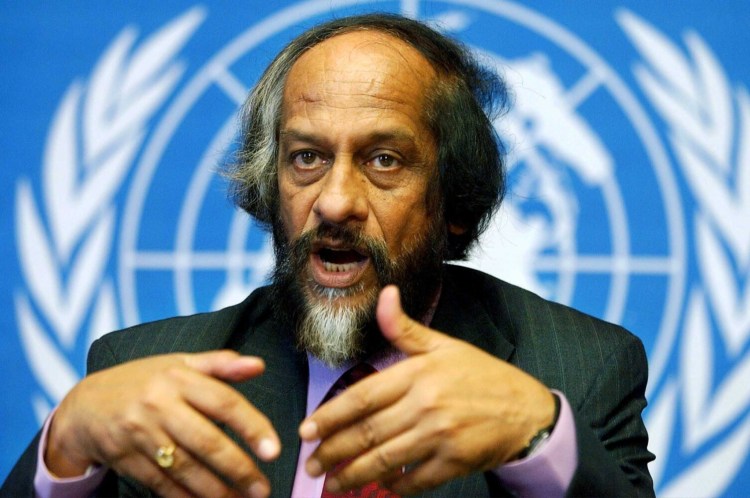

Rajendra Pachauri, an Indian engineer and economist who led the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for more than a decade, championing climate science and leading the panel when it received a share of the Nobel Peace Prize, only for his career to unravel in recent years amid allegations of sexual harassment, has died at 79.

His death was announced by the Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), a New Delhi research organization he had led for more than 30 years. Additional details were not immediately available, but Pachauri had a heart ailment and had been hospitalized in New Delhi, according to the magazine India Today.

His death came after years of court proceedings in India, where he was accused in 2015 of sexually harassing a female employee at TERI. Pachauri denied the harassment charges, and two additional women alleged similar misconduct against them. A 2016 story in The Caravan, an Indian newsmagazine, suggested he “had, for years, been systematically harassing women employed at TERI,” and alleged that the institute had “fostered a tacit acceptance of Pachauri’s conduct.”

Pachauri, known to friends and colleagues as Patchy, was perhaps an unlikely soldier in the war against climate change, having worked in a diesel-locomotive factory early in his career. He later received a doctorate in industrial engineering and economics, advised corporations and Indian government committees, and focused on energy and sustainability issues at TERI before taking on a second position at IPCC, the world’s premier climate change authority.

As IPCC chairman from 2002 to 2015, he supervised the U.N. climate science body at a time when researchers’ credibility was increasingly under attack, questioned by skeptical politicians and industry leaders who opposed efforts to curb planet-warming emissions.

Formed in 1988, the IPCC mobilizes hundreds of scientists to review findings on climate change and its potential implications. In recent years, the panel has warned of dire consequences – supercharged storms, rising seas, devastated coral reefs – from global warming, with an average increase of 2 degrees Celsius emerging as a critical threshold. A 2014 report completed under his watch served as the key scientific text for the climate agreement negotiated in Paris the next year.

Pachauri was at first widely praised for his leadership of the group, with Foreign Policy magazine crediting him in 2009 with “ending the debate over whether climate change matters.” He was later accused of insufficient transparency and sloppy science, notably over a passage in an IPCC report that falsely suggested Himalayan glaciers might melt away by 2035.

He also rankled many scientists with his opinionated statements on climate change and energy policy, as when he once jokingly suggested that climate-change deniers and obstructionists should receive a “one-way ticket to outer space.” “In my opinion, IPCC succeeded in spite of his chairmanship,” said British chemist Robert Watson, his predecessor as IPCC chairman. “He made too many political statements, which did not help move those who were skeptical.”

In an email, Belgian climatologist and former IPCC vice chairman Jean-Pascal van Ypersele said Pachauri “helped to put the climate change challenge and the science behind it on top of the international agenda” and played a key role in syncing climate policies with sustainable development. “Unfortunately,” he added, “he was sometimes overconfident,” refusing to “quickly acknowledge and correct” relatively small errors like the Himalayan claim, part of a landmark 2007 climate report.

Pachauri was a vice chairman of the IPCC before being elected chairman, reportedly after drawing the support of auto manufacturers, oil lobbyists and the U.S. State Department, which expected he would be less of an outspoken environmentalist than his direct predecessor, Watson. At the time, environmental activist and former vice president Al Gore dismissed Pachauri as the “let’s-drag-our-feet candidate.”

“It turned out that, if anything, he injected more of his opinion into the rollout of the reports,” said Andrew Revkin, who reported on climate change for The New York Times and now directs a communications initiative at Columbia University’s Earth Institute. “The statements made by him and other leadership had that tone of ‘we need to act.’ ”

In 2007, the panel released its fourth major climate change assessment, concluding that climate change was “unequivocal” and was primarily driven by human activity. Comprising several thousand pages rich in technical detail, the report generated international headlines with its warnings of potentially catastrophic effects from rising temperatures.

Later that year, the IPCC shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Gore. The Norwegian Nobel Committee praised “their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change.” Pachauri said the panel put its roughly $670,000 prize winnings into an account to help poor countries respond to climate risks.

“His dedication to advance the science and raise global awareness of the climate crisis will endure,” Gore said in a statement after Pachauri’s death.

As the IPCC’s report was examined more closely, some environmentalists said it was watered down; others accused it of overstating the risk of climate catastrophe, cherry-picking research and drawing on sources outside of peer-reviewed journals in a way that jeopardized the panel’s standing as a meticulous and authoritative body.

Pachauri faced calls to resign, which accelerated after reports in Britain’s Sunday Telegraph accused him of financial impropriety. (The paper later apologized for the claims.)

“They can’t attack the science so they attack the chairman,” he told The Guardian in 2010. “But they won’t sink me. I am the unsinkable Molly Brown. In fact, I will float much higher.”

He stayed on for another five years until a 29-year-old TERI employee accused him of sexual harassment, alleging that Pachauri sent her inappropriate messages after she spurned his advances. An internal TERI investigation later supported her claims, and he faced sexual assault charges in court beginning in 2016.

Rajendra Kumar Pachauri was born in Nainital, a Himalayan resort town in what was then British colonial India, on Aug. 20, 1940. He studied at La Martinière College, a private school in the northern city of Lucknow, before enrolling at North Carolina State University in Raleigh. He received a master’s degree in industrial engineering in 1972 and a doctorate two years later.

Pachauri became TERI’s chief executive in 1981 and presided over initiatives including Lighting a Billion Lives, in which he sought to distribute solar lanterns to villages throughout India.

He married Saroj Puri, a physician and medical researcher. His daughter Shonali Pachauri is an energy scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria; another daughter, Rashmi Pachauri-Rajan, co-wrote a book of poetry with Pachauri in the early 1990s. Pachauri also wrote a racy romance novel, “Return to Almora” (2010), while jetting across the world for the IPCC.

Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

In interviews through the years, Pachauri repeatedly sought to highlight the plight of low-lying nations such as the Maldives, an Indian Ocean archipelago at risk from rising sea levels, and called on his fellow citizens in India and beyond to clean up rivers, stem emissions and take action on behalf of the environment.

“The larger picture is solid, it’s convincing and it’s extremely important,” he told The Guardian in 2010, urging critics of the IPCC to recognize the stakes of climate change. “How can we lose sight of what climate change is going to do to this planet? What it’s already doing to this planet?”

Copy the Story LinkComments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.