Line is arguably the most fundamental tool of art, the essential building block for drawing and painting, and an indispensable device for conveying perspective, depth and dimension. Abstract expressionism is a possible exception, though even some of that depends upon line for its rhythm and energy (behold Jackson Pollock). Paul Klee said, “A line is a dot that went for a walk.” And oh, what variegated paths line travels in “Walk the Line,” up through May 8 at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockland.

The eight artists whose work is on display spans a variety of media, including assemblage, artist’s books, painting, photography, printmaking, sculpture and textiles. No matter what medium they’re working in, however, line – expressed as a mark traveling from one point to another, or as a means for defining geometric forms – is a primary concern.

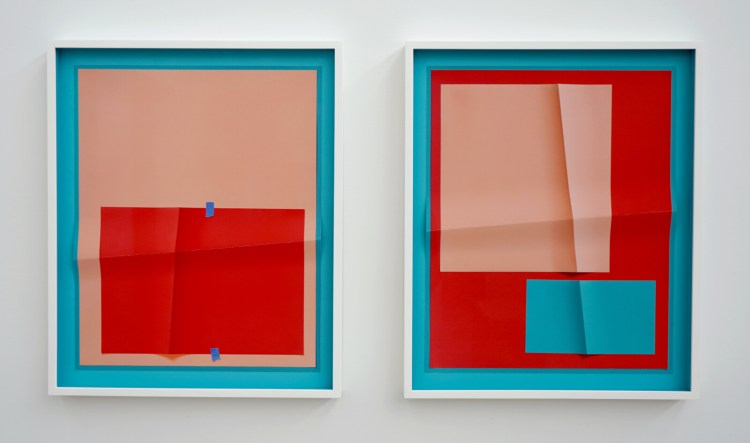

The show starts off with sublimely serene works by Los Angeles-based John Houck, whose connection to Maine is the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, where he spent part of 2008. When I say sublime, I mean they are incredibly delicate and beautiful, with colors that seem to instantly still your mind.

However, you might be surprised that the longer you look at Houck’s pieces, the more confounding they seem, and the more they disrupt your sense of serenity. The only thing of which you can be certain is that they are archival pigment prints Houck has creased once before framing. Sounds simple, right? Not at all. Houck paints geometric compositions then photographs them before creasing the print. Still think it’s simple?

Consider “Accumulator #34.2, 3 Colors Each #009AB2, #F7BA9E, #F86367” (the numbers refer to specific Hex colors he uses). Is the image we’re looking at merely a creased photo of a painting? Or did Houck begin by building a collage of creased papers that cast the shadows we’re perceiving, then photograph the collage and crease the resulting print? Are the fragments of blue painter’s tape actually on the surface of the print, or were they elements in an original collage? If the initial work was painted, did he then apply the tape before photographing it?

You could spend hours trying to figure it out, yet there’s something profoundly beautiful about the way these works convey a Riddle-of-the-Sphinx sense of mystery and otherworldliness.

Grace DeGennaro, left to right, “Emanation (Dusk),” “Emanation (Night),” “Emanation (Dawn),” all 2021, oil and cold wax on linen

Grace DeGennaro’s “Emanation” paintings (“Dusk,” “Night” and “Dawn”) also require extended contemplation to fully appreciate. They are superficially simple. In all, a white circle at the center floats in a green square that in turn floats in a blue circle. Around this central element are mottled fields of shaded color signifying the different times of day in their titles: red washing into orange (“Dusk”), an impenetrable black (“Night”) and yellow seeping into golden orange (“Dawn”). Radiating out of each white circle are lines made of hand-applied dots.

But don’t be fooled. The longer you look, you might notice that the lines of one work presage the color washes of the next, effectively but subtly moving us through the diurnal sequences of our days. To wit: the dots in the radiating lines of “Dusk” are black and white like a starry night sky, and the yellow dots of “Night” indicate the sun emerging above the horizon in “Dawn.”

There are also other possible readings. The radiating lines superimpose the cosmic patterns and sacred geometry of the universe. They all emanate from what might be the white void of emptiness from which all manifestation arises. They might also be mandalas that function to focus our attention and induce a meditative state.

Jeff Kellar is well known for his formalist geometric abstractions. He employs line and blocky flat color to telegraph a deceptive sense of dimensionality. All depict walls and corners in space, and it is fascinating to see the versatility he achieves simply through the use of lines that are straight up and down or diagonal on the canvases. It is also surprising to feel the sense of confinement intimated by the wall paintings in particular. There is no way through these walls; the viewer must go around them to resume directional movement.

Jennie C. Jones, “Score for Sustained Blackness,” 2016; collage, acrylic, and ink on paper in 10 parts

Jennie C. Jones deploys mostly vertical lines of different lengths and spacing to create graphic “scores.” Using collage, acrylic and ink on paper, they appear to chart, like an EKG print out or the sonic rhythms tracked by an LED display on your stereo, the pulses, beats and syncopations of jazz and other Black musical forms.

It should be noted that it is rare to find a woman, let alone a woman of color, working in a cool, minimalist strain of geometric abstraction dominated by white men. Her “Score for Sustained Blackness,” then, is a kind of revolutionary act that upends our assumptions about both who makes this kind of work and what the significance is, if there is any, in the moniker “Black art.”

Not all lines in the show are drawn or painted. Philippines-born artist Paolo Arao makes sewn fabric “paintings” out of textile scraps and hand-dyed materials. They are, of course, all about geometry and line – thick rectangular swatches, thinner strips, square and triangular cuts, etc.

Paolo Arao, “Evolving Quilt Project,” ongoing; sewn canvas, corduroy, cotton, denim, silk, wool

But more subliminally they explore ideas of queerness. Geometric abstraction is, in its broadest sense, a genre that places great focus on control, rigor and formal structure. It is mathematical and intellectual. By using fabric instead of pencils or paint, Arao is softening this rigidity and constriction and questioning the meaning of “straight,” both literally and in terms of sexuality.

Of course, the explosion of color acknowledges the rich diversity of human experience. Arao has also said his work references the textile arts of the Philippines and of African American quilting. Yet, though he was a mere child when the AIDS Memorial Quilt project got underway in 1985 (he was born in 1977), Arao surely is also alluding – especially in “Evolving Quilt Project” – to the now 54-ton tapestry displaying nearly 50,000 panels commemorating the death toll of another pandemic that many remember only dimly today.

Will Sears’s works depict line using narrow strips cut from weathered signs (he was a sign painter for years and is still enamored of the form), which he alternates with smooth wood strips of pure, glossy color. These assemblages are painstakingly precise, yet the flaked paint segments give them an ingratiating folk-art quality that makes them instantly accessible. They are minutely and meticulously puzzled together in a labor-intensive process that yields myriad effects.

Will Sears, left to right, “Canopy I,” “Canopy II,” both 2020; oil enamel, wood assemblage

“Canopy I” and “Canopy II” have a strong sense of dimension that comes from both their shapes and the use of a fluorescent red line that makes them appear like two-dimensional neon signs announcing a motel or roadside bar. He has also said they contain “hidden codes of life,” perhaps some of the very same codes and systems Arao is trying to disrupt in his fabric paintings.

For his “Convergence Series,” Clint Fulkerson makes colorful wavy-lined drawings using vector graphics software to reproduce rhythms of nature. “Convergence Series 4 #3” feels like a dizzying vortex that draws you into it. “Convergence Series 8 #6” looks like waves in a magnetic field.

Finally, don’t leave without flipping through Paula McCartney’s artist books. My favorite: one that shows light patterns on a wall that she reproduces in white ceramic. The actual unglazed black stoneware pieces on the table are more obviously about line. Yet the poetry of giving form to something as ephemeral as light is an unexpectedly affecting coda to the show.

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland. He can be reached at: jorge@jsarango.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story