Artists have used series as a way to explore phenomena of nature, light, time, space and color for centuries. From 1890 to 1891, Claude Monet chronicled his perceptions of light over 25 canvases portraying haystacks in the surrounding fields of Giverny. Josef Albers began painting hundreds of variations on the theme of a square in 1949 to investigate the effects of chromatic interactions between three or four gradations of colors. And On Kawara’s 3,000-plus multidecade “Today” paintings are conceptual meditations on time and place.

Meg Brown Payson does something similar in “Asleep On the Dock” (through April 29) in the downstairs gallery of the Press Hotel. Payson has long been known for her infinitely layered abstractions of biomorphic forms. I have always looked at these works as poetic contemplations on the origins of life.

Many have appeared to me like something you’d see under a microscope on a slide moistened with a drop of swamp water, where living organisms normally invisible to the naked eye wriggle and swim. In terms of evolution, at one time they might have been the primordial building blocks of mammals that first swam, then walked, on land.

Depending on their palette, Payson’s paintings can also remind us of planetary phenomena such as births of galaxies and other cosmic fulminations. In this sense, the six large panel paintings on display are not anomalous; they still transmit the concept of creation, of life emerging and reproducing.

But the show’s title, as well as the names of individual works (all produced during a residency at the Ellis Beauregard Foundation in Rockland), indicate that she has narrowed her view considerably to evoke a very specific sense of place. “Paying attention is a potent kind of love,” reads a wall plaque. “I live where I grew up; these paintings recall times floating in and on Maine waters, looking down through seaweed and up through clouds. Like space, like memory, the paintings are layered and altered in time.”

In “Hot Moon” – a composition of indigo, cerulean and cobalt blues – we feel underwater, looking up through aquatic plant forms at the pale white lunar glow of the title. Through her layering of acrylic paints and organic forms, as well as the size of the panels, Payson summons a palpable sense of submersion in the saltwater of Casco Bay.

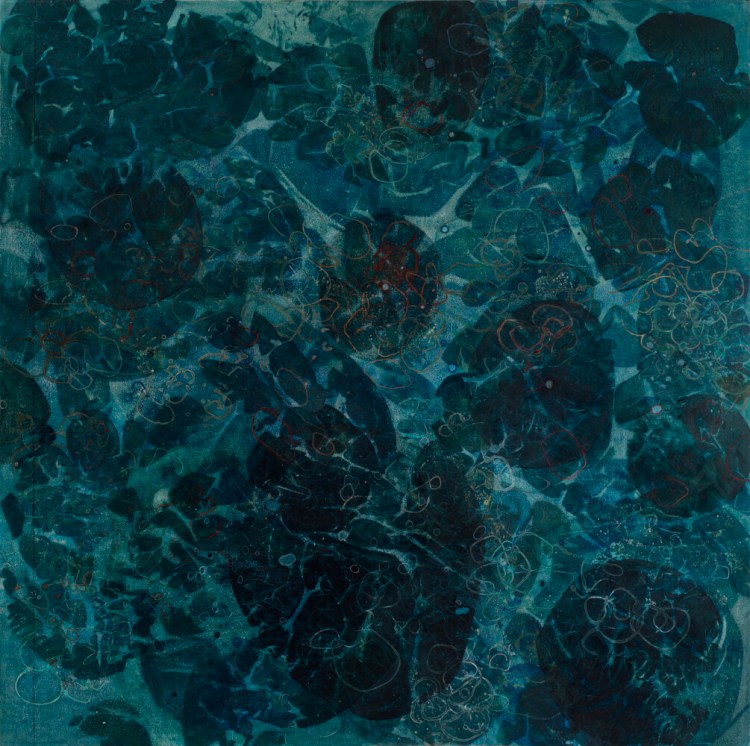

There is also a similar effect in “Midnight Glimmer,” though the palette and density of forms here creates a murkier scrim through which we view that light. It is greener and grayer, which indicates, at least for me, a lake rather than the ocean (like “Hot Moon”).

What creates the sense of liquidness and underwater perspective, I realized the more I looked at these two paintings, are squiggly outlines – some solid, some made with tiny dots – which convey the rippled surface of water being gently disturbed by breezes and/or the movements of currents underneath. David Hockney depicted these in his famous pool paintings as networks of capillary-like lines in white or pale blues. Payson uses a different technique but conjures the same sense of water perpetually in motion.

Meg Brown Payson, “To The Shore”

The most successful works here, in my view, are “To the Shore” and “Rockweed,” which hang opposite each other in the gallery. “To the Shore” is a resplendently green three-panel piece. Payson’s forms are larger and more opaque here than in other paintings, some of them appearing veined like leaves. And that is exactly the memory it calls to mind. We are not underwater here; we’re looking down on a blanket of leaves floating on the surface of a lake that have gathered along the shore. The presence of yellows makes that surface look sunlit on a hot summer day.

“Rockweed” feels, alluringly, more mysterious. That’s because we can’t quite pinpoint what we’re looking at. Globular translucent blue shapes seem suspended above coral and salmon shades. There is so much light emanating from underneath – as if from a deep heat far below the surface – that it feels otherworldly.

Payson also paint-soaked foam beads normally used as a medium for flower arrangements and sprinkled them randomly across the panel. The beads are no longer present (I’m not sure if they were removed or dissolved into the surface). Only their tiny bubble-like presence remains. This same method is deployed in other paintings. But the sheer density of these tiny round shapes here gives the painting a kind of visual effervescence, as if this enigmatic light is heating the liquid being depicted, sending masses of tiny bubbles to the surface.

Meg Brown Payson, “Rockweed”

Rockweed, of course, is a kind of seaweed common along the New England coast. It is characterized by long flat fronds attached to air bladders that keep the plants afloat, thus enabling the rockweed to carry out photosynthesis. Yet the painting bears no hint of the plant, which is usually green or brown. No form indicates it either.

Only its sense of profundity and its blueness make “Rockweed” feel watery. But it could just as easily intimate hot gasses of the universe, in this way suggesting a more general act of spontaneous creation. There is richness in its lack of discernible association. Which brings up an interesting point: Payson’s technique is itself fluid in the sense that it works both abstractly and representationally on various levels.

The ability to tie abstract forms to something we can identify, however loosely, works for paintings like “To the Shore” or “Hot Moon.” Conversely, the inability to do this with a work like “Rockweed” – despite a title that might lead you to a specific conclusion – not only also works, but succeeds even more powerfully because it draws you into something more intangible and, so, almost mystical.

Meg Brown Payson, “Sun In My Eyes”

Interestingly, too, a painting like “Sun in My Eyes,” while certainly brightly painted, feels more decorative, almost like a fabric or wallpaper pattern. In this case, neither abstraction nor an ambiguous idea of representation elevates the work to the same level as “To the Shore” or “Rockweed.”

You can contemplate this and other questions at any hour since the gallery is in a hotel that’s open 24/7. So, if you happen to be an insomniac, Payson’s paintings might provide a particularly fruitful way to spend your waking nighttime hours.

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland. He can be reached at: jorge@jsarango.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.