A sports writer for the Tampa Tribune called me up one day in the spring of 2002, asking for Stephen King’s phone number. The guy wanted to write a funny story about how King must have put some kind of hex on the Tampa Bay Rays.

King – a master of horror and a gigantic Red Sox fan – was at the game in Tampa when the team’s epic 15-game losing streak began. The sports writer’s theory was that it must be King’s doing, and he wanted to do a story on it, with comments from King. I told him, sure, I’ve been covering King for years, I can give you a number. But I doubt he’ll call you back. He doesn’t always call me back.

Yet King called the guy in minutes. He was so gregarious and engaging that the Tribune writer called me again, to thank me. That’s great, I told the guy, I am so happy for you.

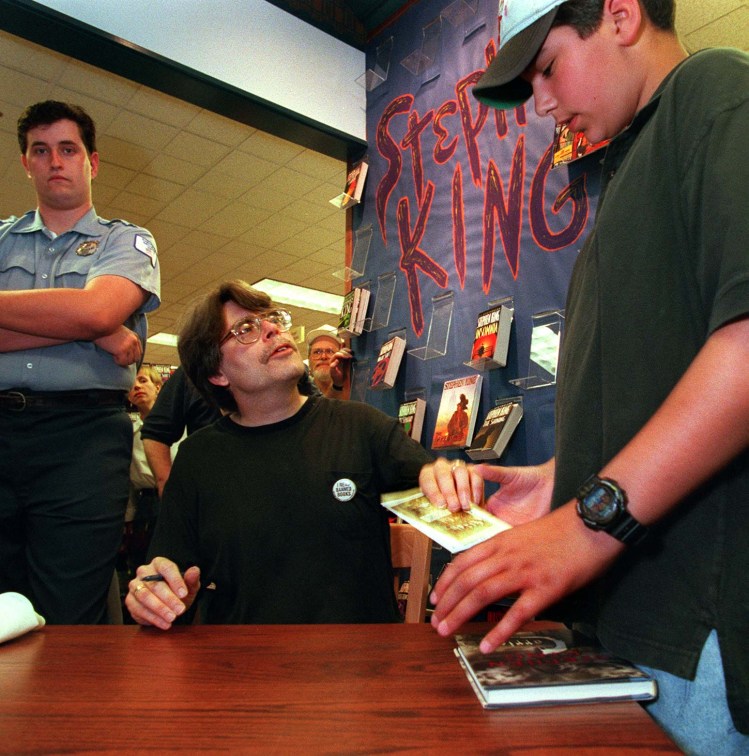

Ray Routhier has been covering and talking to Stephen King for more than 25 years. Gregory Rec/Staff Photographer

I’ve covered King for the Press Herald for more than half his career, since the mid-’90s. As an entertainment reporter in Maine, he’s a big focus of my beat. King, 76, has had an outsized impact on publishing, films and pop culture since his first novel, “Carrie,” came out 50 years ago this month.

So I probably ask him for interviews at least once a year, when new books or movies come out, he wins a major award or he reaches some career milestone. I’ve gotten to talk to him maybe 40 percent of the time. Not a bad average when you figure he’s a very busy guy, and I’m competing against hundreds of national and international reporters for his attention.

Given his worldwide fame, he’s pretty accessible to reporters, and anyone, in Maine. Over the years, he’s showed up to give talks at schools, libraries and his alma mater, UMaine.

King has talked to me with more frequency as the years have gone on. Maybe because he realized I wasn’t going to leave him alone. I’ve learned over the years that he’s more likely to respond when the topic is not strictly about him and his lofty accomplishments. Or when it’s something close to his heart, like baseball, his home state or his hometown.

When I reached out to him in 2021 for a story about efforts to have more films made in Maine, and grow the film industry here, he immediately agreed to talk. He said he’d love to see more of his stories filmed in Maine – as some had been in the ’80s and ’90s – and he thought increasing tax credits and other incentives for film companies would help.

When I emailed him last October, two days after the mass shooting in Lewiston, he called back within five minutes. King grew up in the small town of Durham and went to school in Lisbon Falls, where police were searching for and later found the gunman. He’s also an outspoken advocate for stricter gun laws. When I called, he said he had been watching TV coverage of police swarming on roads he walked as a kid and searching near the mill where he worked as a teen. He felt compelled to speak out and was willing to talk to me for a story.

“We live in a rural state, neighbors get along, we have a tendency to pull together in hard times, so there probably was a feeling that it can’t happen here, but it can, and it will again,” King told me. “Guns are everywhere. This guy was crazy, and he was able to get guns and nobody was able to take them away.”

Several times during that interview, he said, “I got nothing, Ray, I got nothing,” as if he couldn’t find the words to adequately express the horror of what had happened.

In 1999, I was working on a big story about King’s life and career, pegged to the 25th anniversary of “Carrie.” My co-workers knew how desperate I was to talk to King for that story and thought they’d have a little fun with me. I got a call one day from a woman who said she was King’s secretary and that King would talk to me in Portland’s Old Port, while he was getting his hair cut at a salon, if I brought him a sandwich from Portland Wine and Cheese.

I wrote the information down, extremely excited that I’d finally get to talk to King face to face. But when I hung up the phone, I started to think something was amiss. By 1999, I was well acquainted with King’s Bangor-based assistants – Marsha DeFilippo and Julie Eugley – who were always extremely nice to me. Neither of them has a vaguely Southern accent, like the caller had. I made some calls and found out that neither of King’s assistants had called me; instead, a coworker’s mother from Cincinnati had been enlisted to pull the prank on me.

A couple weeks after that “Carrie” anniversary story came out, with no quotes from King, I saw him at a Portland Public Library event, held at the Holiday Inn By The Bay. Afterwards, he told me had seen the “Carrie” story and thought it was “a good piece” and that he’d be happy to talk to me at length at some future date. But he was most animated that day when talking about rumors flying around that the owners of the Red Sox wanted to tear down historic Fenway Park. I don’t remember his exact words, but he was pretty upset.

In June 1999, King was hit by a van while walking near his Lovell home, in western Maine, and very badly hurt. He suffered broken bones and a collapsed lung, which caused recurring health issues for him.

As I’m writing this, Eugley, his assistant, has just emailed to say King wouldn’t be able to talk to me about the 50th anniversary of his first novel, because he’s dealing with some medical issues.

Stephen King during a panel discussion on campus activism at the University of Maine in Orono in 2001. Photo by Herb Swanson

In the fall of 2003, King won a National Book Award for lifetime achievement. I made my routine interview request, and as luck would have it, he was upset about a story someone from the national media had done on him, so he agreed to talk to me, the local guy. I was flattered.

Then a few months later, something very weird happened – even weird by Stephen King novel standards. In early 2004, I heard that a new TV series, “Stephen King’s Kingdom Hospital,” was premiering. So I made my obligatory interview request to DeFilippo, who, to my surprise, said she was glad I’d called and that she’d been trying to get in touch with me.

She offered me a “good news, bad news” scenario. The good news, she said, was that King wanted my permission to use my name in an upcoming “Dark Tower” book. The bad news was that he was recovering from pneumonia and couldn’t do the interview about the new TV show.

A few days later, I got a very nice email from King.

“Dear Ray, at the end of my forthcoming novel, SONG OF SUSANNAH (Volume VI of The Dark Tower), a fictitious June 1999 clipping from the (Maine) Sunday Telegram is displayed, featuring a very large headline reporting (fictitiously of course) my death as a result of being hit by a van in Lovell, followed by a brief article.

“It would tickle me – and I hope you – if I could use your byline for the article. Would you have any objection to this form of homage? And if not, would you mind scrawling your signature at the bottom of this letter to reassure my publisher. Sincerely, Stephen King.”

I signed, of course. At some point a little while later, DeFilippo emailed me to say King would, indeed, talk to me about the new TV show. She said the only other interview he was giving about the show was to the New York Times. Again, I was flattered.

During that interview, I asked him why he wanted to use my name, out of all the reporters he must deal with. He told me he wanted to use a Maine reporter’s name, and since I had written “a bunch of stuff” about him, I seemed like a logical choice.

Now, 20 years later, I’m surprised how often people tell me they were just reading “Song of Susannah” and saw my name, or heard it while listening to an audiobook.

I guess it’s not really that surprising. It’s just the power of Stephen King.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.