The photographer Rose Marasco has learned to be kind to her maker self.

She pursues her work with purpose, but not intent. She likes to experiment, but doesn’t worry if her experiments fail. She believes there is no right or wrong decision, and that each decision, no matter its outcome, leads to new discoveries. As an artist, Marasco’s core motivation is discovery.

“I have learned to trust that I am going to end up where I need to be,” Marasco said. “If it works, I pursue it. If it doesn’t, that leads to something else. My work tends to roll along. I follow a thread that always leads somewhere else.”

Evidence of her experiments will be on view across southern Maine this summer. The Portland Museum of Art hosts her first retrospective, “index,” through December. On June 5, the Ogunquit Museum of American Art opens “Rose Marasco: Reflections on Patrons of Husbandry,” featuring work from her widely seen Maine Grange series from two decades ago, and the Art Gallery at the University of New England in Portland will include her New York photos in a group show that opens in late July. In addition, the Center for Maine Contemporary is showing another New York photo in “Highway & Byways,” on view through Saturday at the Portland Public Library.

In a season packed with visual art exhibitions worthy of attention, this is the summer of Rose.

Marasco is a prolific photographer and active in the national scene. She’s never had a particular style, and always looked for new and different ways to express herself visually. She uses many cameras – 35mm, pin-hole, large-format, instant – but doesn’t fuss over gear. “I see (the camera) as a material, no better or no worse than any other,” she said, attributing her camera choice to convenience and circumstance. “We don’t talk about the brushes painters use. Why do we want to talk so much about the cameras photographer use? The camera one uses really is not that important, as long as it works for you.”

MARASCO DOES NOT seek pretty pictures, nor is she interested in making lush landscapes or revealing portraits. Instead, Marasco focuses on point-of-view, orientation and other aesthetic concerns that prompt us to consider what we see, how we see it and why we observe things the way we do. Black and white and color both appeal to her. She prints on different kinds of paper. She frames some of her work to hang on the wall in a traditional manner. Others she tacks up casually.

She challenges our perception of what a photo is, and treats her work as a composer might treat a symphony or how a writer approaches a novel. Her photos convey meaning through a visual narrative that is often layered and complex. They tell an in-depth truth, told through Marasco’s visual filter.

“She’s always asking, ‘How can I tell a story in a fresh way?'” said Jessica May, the PMA’s chief curator. “She has a restlessness and energy that speaks to the seriousness of her creative endeavors.”

Julia Van Haaften added many Marasco photos to the collection of the New York Public Library when she worked as curator of photography. She called Marasco “enormously adventurous. She’s certainly psychologically adventurous, and there’s aesthetic adventurousness about her work, as well.”

MARASCO’S STORY BEGINS in upstate New York. She grew up in Utica in an Italian family, and was given her first camera when she was young. Taking photos came naturally, she recalls. She never stopped. She studied photography in college, first at Syracuse University, where she earned her bachelor’s degree, and later at the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York, where she completed her master’s.

A career educator, Marasco came to Maine in 1979 after answering an ad for a job opening in the art department at the University of Southern Maine. She taught there 40 years, retiring in 2014 with the title distinguished professor emeritus. She attributes her wandering creative spirit to her interactions with students, who ask questions, challenge assumptions and push new ideas forward. Her students have helped keep her work fresh, she said.

We see evidence of her active creative mind in “index,” which is part of the museum’s Circa series that focuses on contemporary art. This show is bigger than most Circa shows at the PMA, in part because May had so much to work with. She spent dozens of hours with Marasco, reviewing 45 years of work from 1971 and conducting long interviews about process and creativity. Their conversations are included in a catalog.

The show spreads over two floors – the third and fourth – and involves hundreds of images. It’s so large, the museum built temporary display walls to accommodate it. The exhibition includes images from several series Marasco has completed, with subjects that range from the dense urban environment of Manhattan to the serenity of Gilsland Farm in Falmouth and the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire, where she received an artist residency in 1985.

We see the inside of her Winter Street home in Portland’s West End, where she has a studio and shoots constructed photos and still lifes. We see familiar Portland landmarks (the Hay Building, for one), and scenes from Utica, Westbrook and Portland.

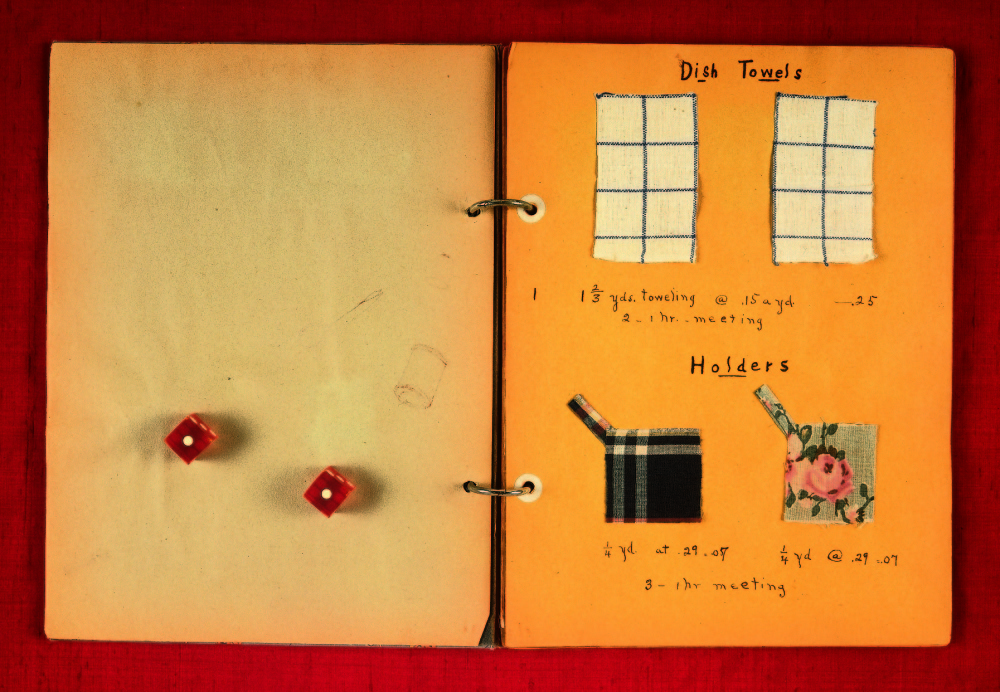

And we see photos from Marasco’s Grange Hall series, which she completed in 1990-91. She shot exteriors in black and white and interiors in color of 100 Granges across Maine. The Maine Humanities Council supported the project, which allowed it to travel. The Grange work earned wide exposure, and was an important rung in her professional ascent. Marasco won the Exhibition of the Year award from the New England Historical Association.

While many viewers will recognize the Grange photos, “index” offers a broad perspective of Marasco’s work. “A retrospective allows you to look and listen and learn about how creativity unfolds in one person’s life,” May said. “It allows us to answer the question, ‘How do you tick?'”

Marasco ticks like a scientist. At MacDowell, she made a photo a day with an instant camera, because she was curious what she would see. On the streets of New York, she uses a pinhole camera in a body of work that continues. At her studio in Portland, she manipulates content, blending and juxtaposing photos, projecting images on walls to create dream-like compositions.

The images blur reality and abstraction. That’s how Marasco sees the world – and how she believes we all see it. “I think Rose is interested in pushing photography toward unreality,” May said.

FORMER PORTLAND gallery owner Andres Verzosa curated the Ogunquit show, and chose work from Marasco’s Grange series. It overlaps with the PMA show, and gives people more opportunities to view a deeper selection of photos. He planned the Ogunquit show as a companion exhibition. Many Maine museums and cultural institutions are showing photography this year as part of the Maine Photo Project, he noted.

He’s long admired Marasco’s work ethic and role in Portland’s art scene. Apart from her own career as a photographer and educator, Marasco has worked to create affordable and functional housing for Portland artists, he said. And she was a role model when he returned from New York in the early 1980s. A gay man, Verzosa felt more comfortable expressing his sexuality after he observed Marasco and her partner openly express theirs.

“Coming out and being gay and comfortable in your own identity was a big thing in the 1980s,” he said. “Looking at someone like Rose, I had a natural curiosity – ‘Oh, she’s like me.’ And I aspired to be like her – not her directly; I didn’t become a photographer. But knowing there was someone in our community who seemed to be ‘normal’ and doing good things and heading a photo department and doing important work was inspiring.”

Marasco and her partner came to Maine in 1979 knowing no one. She took a chance on a fledgling art department at USM, and helped turn it into one of the school’s strongest academic programs. She stayed for 40 years at USM, and has no intention of leaving Portland.

“People stop me everywhere,” she said. “They want me to know how happy they are about the show. They want me to know they’re with me and that they support me and my work. It’s very gratifying.”

Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.