ATLANTA — Living with a fatal degenerative disease, Susan Caldwell relied heavily on the support of a Georgia-based right-to-die group. In 2008 she strapped on a helium-filled hood in an ultimately unsuccessful suicide attempt, and just knowing that the group – the Final Exit Network – was there for her gave her peace of mind.

Then, in 2009, the organization went on hiatus in Georgia when four group members were charged with assisted suicide. Awash with anxiety, Caldwell filed suit last week asking a federal judge to let the group assign her an “exit guide” who could hold her hand and guide her through her final hours if the pain of living becomes unbearable.

“It is not the illness I fear, it is the suffering it causes,” she said. “Final Exit Network provided relief and compassion to people like me.”

A former software engineer, the Atlanta woman claims in the suit that Georgia’s assisted suicide law is vague and unconstitutional. She contends it violates her free speech rights because it blocks her from seeking the advice of right-to-die groups.

Caldwell, 43, has Huntington’s disease, a genetic disorder that usually leads to dementia, difficulty speaking and involuntary movements. The disease, which afflicts an estimated 30,000 people in the United States, is passed from parent to child, and there is no cure. Most people die about 15 to 20 years after developing symptoms.

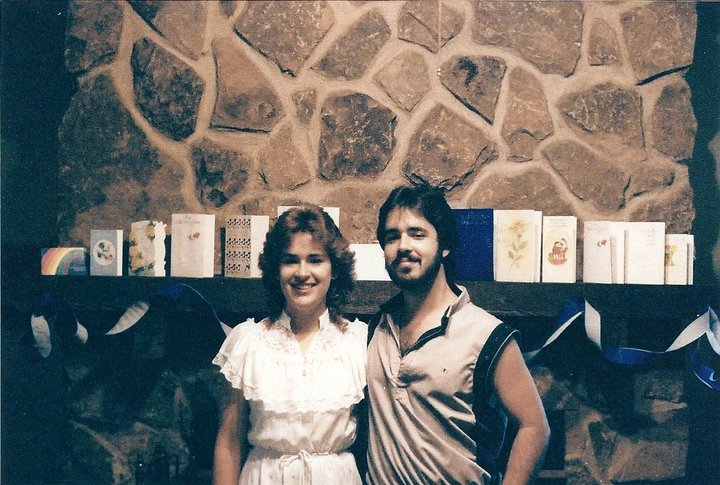

Caldwell’s grandfather and uncle had it, and in 1985, at the age of 42, her mother, Glenda, grew so fearful that her children would develop it that she shot and killed Caldwell’s 19-year-old brother and then shot at but missed Susan, who was then 18.

Glenda Caldwell was sentenced to life in prison, and she was diagnosed with the disease while serving time.

Susan Caldwell was diagnosed with Huntington’s in March 1994, a few months before her mother was released. A 1994 retrial had found her not guilty by reason of insanity, in part because of her daughter’s testimony.

Glenda Caldwell died in 2002, the same year that Susan Caldwell began suffering from the symptoms of the disease.

By August 2008, she said she was so concerned that her extended family would be burdened by her for years that she attached a helium tank to a hood and tried to kill herself, a method outlined in a best-selling suicide manual by British author Derek Humphry.

It’s the same method used by the Final Exit Network, though the group recommends having “exit guides” to help. The group’s members have bristled at prosecutors’ use of the term “assisted suicide,” saying they don’t actively aid suicides but rather support and guide those who decide to end their lives.

Critics say the group sends a dangerous message to society.

“It says that we’ll look the other way when not-so-productive people commit suicide, that they are burdens and that society isn’t that troubled to see them die,” said Stephen Drake of the group Not Dead Yet.

Georgia’s law makes it a felony for anyone who “publicly advertises, offers, or holds himself or herself out as offering that he or she will intentionally and actively assist another person in the commission of suicide and commits any overt act to further that purpose.”

Caldwell’s lawsuit claims the statute violates her free speech rights because instead of criminalizing suicide or assisted suicide, it outlaws people from publicly speaking about assisted suicide and then participating in the death. That means people who only hold the hand of a terminally ill person as he ends his life could be prosecuted, said Caldwell’s attorney, Cynthia Counts.

Georgia Attorney General Thurbert Baker’s office and Georgia Gov. Sonny Perdue’s office declined to comment. But prosecutors have countered that lawmakers intended to ban assisted suicide when they adopted the law.

Caldwell’s previous guides from the Final Exit Network, Ted Goodwin of Kennesaw, Ga., then the president of the group, and member Claire Blehr of Atlanta, were not present at her suicide attempt. In fact, they assessed her case and encouraged her not to end her life.

“They challenged me to see the quality of life that remains, and made me think about how hard this will be on my family when it comes and how important it is for me to fight for as much time as I can have with my family and friends,” said Caldwell.

But her confidence shattered in February 2009 when Goodwin, Blehr and two other members of the organization were charged in the death of John Celmer, 58, after an eight-month probe by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

Investigators said the group sent exit guides to Celmer’s home in Cumming, Ga., outside Atlanta, to show him how to suffocate himself using helium tanks and a plastic hood. Authorities have also raised questions over how carefully the group, whose leaders claim to have been involved in about 200 suicides, screened potential members.

Celmer did not appear to be seriously ill. While his mother said he had suffered for years from throat and mouth cancer, court documents quoted his doctor as saying he had made a “remarkable recovery” and was cancer-free at the time of his suicide. Authorities said he may have been embarrassed about his appearance after jaw surgery.

The four Final Exit Network members have pleaded not guilty in Celmer’s death, and their attorneys contend the charges are baseless.

Caldwell, who is now having trouble swallowing, wants Georgia’s law overturned because she believes she has the right to die. And she believes she has the right to seek the group’s help.

“People are going to commit suicide regardless, and the Final Exit Network offers a peaceful and painless way to die with dignity,” she said. “Having it be peaceful and dignified, and having a compassionate and supportive person who is there to hold your hand and be emotionally supportive of you, is critical.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.