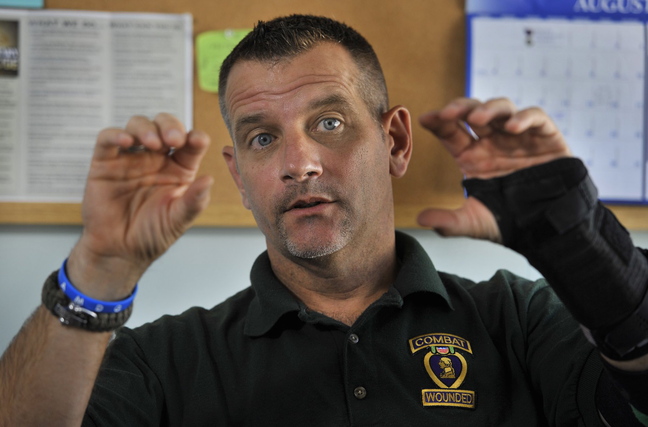

Richard Brewer, once assigned to the elite cadre of Marines guarding U.S. embassies abroad, was stationed at the American Embassy in Beirut, Lebanon, in the midst of that country’s civil war when he heard gunshots on the morning of Sept. 20, 1984.

He was on the second floor of the embassy annex. The original embassy building had been destroyed by a car bomb in April 1983, and the current location in East Beirut was supposed to be secure.

He grabbed his rifle and ran to the patio in time to hear an engine revving and tires screeching. Then a van full of explosives erupted, knocking him back and collapsing the building around him.

He woke up covered in debris.

“What was once the embassy was now kind of burning rubble,” he said. “People were screaming and crying and dead and dying.”

Twenty Lebanese and two American servicemen were killed. Brewer spent the next few hours ferrying the wounded, then set up a security post, despite suffering shrapnel wounds, a broken arm and serious burns.

He eventually passed out – covered in blood, much of it his own. He was treated at a local hospital and soon rejoined four fellow Marines providing security for the ambassador’s residence for the next three days until reinforcements arrived to relieve them.

The ordeal earned Brewer a Purple Heart, the Navy Commendation Medal and a number of other personal and unit commendations. It also left him with severe emotional scars that wouldn’t fully manifest themselves until much later in life.

Thirty years later, Brewer, who since returning to the United States from Lebanon has been a state trooper, a bodyguard and an educator, is now on a different mission: “Debunking myths for vets, families, and the public at large about just what PTSD is and why we’re not crazy.”

That led him to start One Warrior Won, a nonprofit peer support organization based on Exchange Street in Portland, to help veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. The organization, which got started about four years ago, now has two staffers in addition to Brewer and participates in events around the country.

A study by the Department of Veterans Affairs found that 239,000 veterans who have received treatment at VA facilities have PTSD, and a Rand Corporation study concluded that 31 percent of troops returning from Iraq and Afghanistan have PTSD, depression or some form of traumatic brain injury. Other estimates have put the number of veterans with PTSD at between 9 percent and 19 percent.

Brewer believes PTSD is far more prevalent than the estimates.

When President Obama awarded Army Staff Sgt. Ty M. Carter the Medal of Honor in August, he pointed out that Carter sought help for post-traumatic stress. Even the bravest of soldiers suffer from PTSD, he said, adding that seeking help is not a sign of weakness.

The idea that seeking help is weak is one of the hurdles people who have PTSD and their families must overcome, Brewer says.

“Anybody who goes to combat and sees what combat does has PTSD,” he said. “Everybody is going to have nightmares, sleeplessness, be angry, maybe a little bitter. For some it’s going to be much more magnified than others.

“The only question we should be asking our men and women is: ‘To what extent do you suffer from PTSD?’”

Brewer, now 50 and living in Falmouth, himself suffered with PTSD through his post-military career as a history teacher at Cheverus High School in Portland. During his time there, he was selected for the “A+ Teacher Award” in 2002 and given a yearbook dedication in 2004.

Before that, he worked for the Massachusetts State Police and a private security firm in Washington, D.C., and earned bachelor’s degrees in special education and history.

But four years ago, he almost took his own life.

It was, he said, his “God moment.”

He reasoned that his failure to pull the trigger “must mean I really want to live,” and set out to understand why – even though he was successful – he was still depressed. He was eventually diagnosed with PTSD.

“The relief is almost instant, just to know you’re not crazy,” he said.

Brewer has since traveled the country working to educate the public about PTSD and reaching out to veterans.

What veterans with PTSD need is someone who has been through combat himself and who understands the effort of trying to reintegrate into society, he said. And they want to know there’s a path out.

Brewer said there are stages to helping people deal with PTSD:

• The first is helping them become aware of it and understanding how it affects them. It often manifests itself in drinking or drug use.

“What we do is exist, survive. … We’re emotionally numb,” and that can wreak havoc on relationships, he said. At the same time, combat vets can be anxious and easily startled.

• The second stage is developing coping mechanisms.

“It’s never going to go away, but there are ways you can change your life so you can live a better life,” Brewer said.

Brewer said he works with veterans to find activities that help them express and displace some of the negative emotions.

“One of the reasons a number of us suffer is not only because we’ve seen and done horrific things that had to be done in battle, it’s also because we miss the camaraderie and the adrenaline,” Brewer said.

Many of the activities are adrenaline-based: a few days of deep-sea fishing, big-game hunting, ice climbing or whitewater rafting.

“You’re building new experiences, replacing those images,” he said. “You want to capitalize on those shared experiences that are positive.”

And it’s in the midst of those activities that some healing begins, he said.

“There’s something magical about that campfire,” he said, referring to the down time the participants spend after an outdoor activity. “Many of these guys haven’t laughed in quite some time.”

Brewer also tries to show veterans that a constructive outlet such as poetry, art or meditation can help.

• Brewer said his organization is not large, but takes an approach similar to Alcoholics Anonymous in bringing together people with shared experiences so they can help one another. That is the third stage.

“The tip of this pyramid is not only about having your life back. It’s also about reaching back and grabbing somebody else,” he said.

Brewer does public speaking and provides educational services. He also has appeared on television and radio programs.

Over the last four years, he estimates some 400 veterans have reached out for some support from One Warrior Won. “I’m proud to say out of the 400, none of them has committed suicide.”

Brewer believes every combat veteran experiences some degree of traumatic stress, though some cope with it more easily than others.

Maj. Earl Weigelt, a chaplain with the Maine Army National Guard, said it’s admirable to help veterans who need it, but he worries that some people will come to believe PTSD is inevitable.

He is afraid the public will believe that anyone who serves in combat comes back with a severe disability, and that misimpression might hurt recruitment and dissuade some people from a path in the military that might be right for them.

“There’s something called combat operational stress and then there’s something called PTSD,” Weigelt said.

“Folks with PTSD that I have encountered experienced pretty terrible things and – coupled with what they saw – an imminent threat to themselves,” he said. Others have gotten counseling, and while the experience “left a mark,” it does not rise to the level of a disorder, he said.

“It’s important to make that distinction so that individuals who are contemplating military service and currently in military service aren’t going to think there is something profoundly wrong with them if they have some symptomology,” he said.

The Maine Army National Guard and the Reserves have incorporated a goal into the demobilization schedule so that soldiers reconnect with one another after deployment. Once back from serving overseas, units and their families gather monthly for three months to get information about reintegration and reconnect with members of their unit.

Weigelt said those having a great deal of difficulty after deployment have access to counselors at veterans centers throughout the state and at the VA hospital in Togus.

Brewer says that for many combat veterans, the existing system, including the overburdened services of the VA, aren’t meeting their needs.

One Warrior Won is individual and handles a variety of needs, he said. One veteran might need a suit for a job interview. Another might need a service dog. Brewer has advocated for the VA to pay for service dogs for veterans with PTSD.

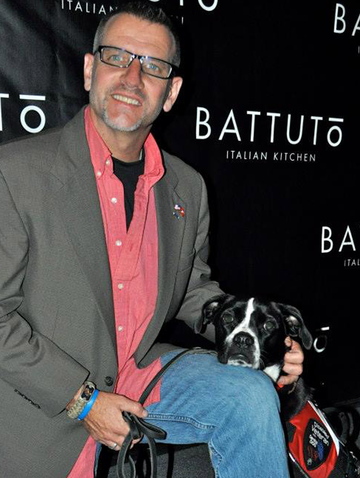

Joel Connick said One Warrior Won helped him and now he’s working with the organization to help others.

Connick is a Portland High School graduate, a Marine and a veteran of the Iraq War, including the battle of al Nasariyah in 2003, where some of the heaviest fighting took place. Connick also fought in Kosovo and Afghanistan. He says he was a mess when he finally came back.

“It was the anxiety and the hypervigilance and the irritability,” he said of his PTSD. “My outlet, it became self-medication. … That’s the only way I could get my body or myself to calm down.

“When they told me I had it, I was embarrassed about it, didn’t want people to know. People would treat me differently,” Connick said. “You feel weak and inferior. Eventually you learn that’s not the case. It’s your brain, that’s all it is. Your brain doesn’t shut off. … It’s still vigilant in that caveman state of survival. That’s why you’re always revved up, stressed.”

Like many veterans with PTSD, he has wrestled with substance abuse and had trouble finding and holding a job.

Working with One Warrior Won, using his painful experiences to help someone else has become an outlet.

“We just kind of take it head on and we can get stuff done a lot quicker than the VA,” he said.

Connick says he doesn’t regret signing up for military service.

“I was part of something bigger than myself,” he said. “It wasn’t the war, it was the brotherhood. It was the guys to your left and right. That’s exactly what it’s about – it’s about your brothers.”

David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

dhench@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.