My mother is of Polish-Lithuanian Jewish extraction; my father is mostly Scottish and British WASP. But much of my culinary heritage, under the constant tutelage of my father, comes from Mexico.

Through most of college in the early 1970s, my dad worked as a waiter and prep-cook at the Casa Mexico, a restaurant in Harvard Square that was tucked away in a basement on a side street. The Cambridge eatery was one of the few places to get Mexican food in all of Boston. (The place closed in 2004, after a run of more than 30 years.)

At the time, few New Englanders considered the taco fast food, let alone fancy fare. California’s Taco Bell was just beginning to sweep the country. But Mexico was on my dad’s mind in that cramped Winthrop Street corner kitchen, where he mixed garbage cans full of salsa, stuffed chiles rellenos and marinated white button “hongos” that the restaurant served as a popular appetizer. That he actually liked fresh mushrooms was a revelation to this now-avid forager.

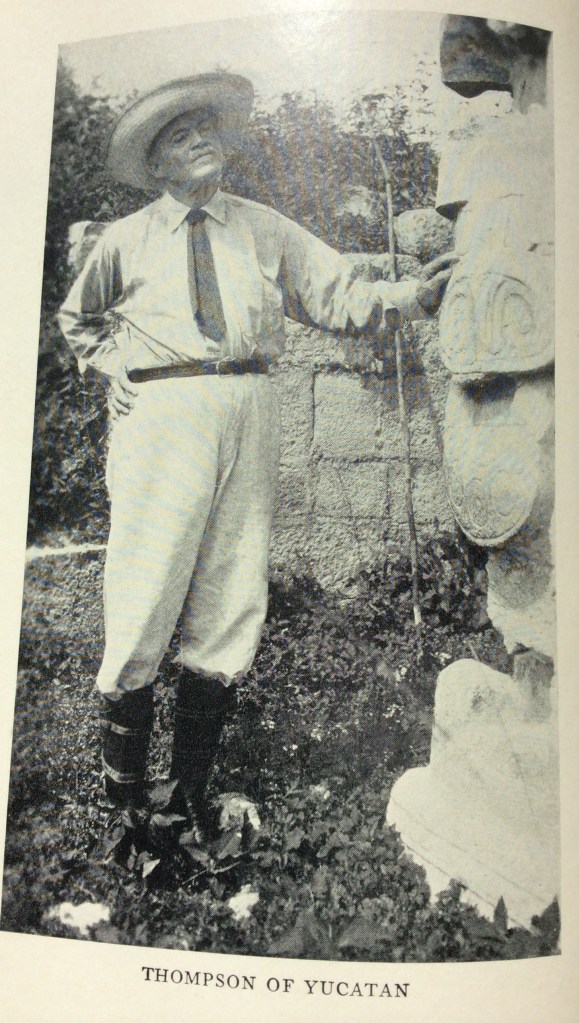

The Casa Mexico job was a fluke – it was convenient, the closest restaurant to his college House. As a senior at Harvard by day, he spent long hours in another basement, combing through the dusty archives of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. There he devoured storage boxes stuffed with the letters and records of his great-grandfather Edward Herbert Thompson, the American consul and Mayan enthusiast who spent 40 years in Yucatán, excavating the Sacred Well within the ruins of Chichén Itzá.

Yet all those old letters failed to reveal a complicated family secret: We apparently have Mexican cousins, blood relatives down in Yucatán, where locals still venerate my great-great-grandfather as Don Eduardo or Papa Grande. Fuzzy details about Carlos Marrufo (Thompson?), who would have been my father’s half-great-uncle, emerged just a decade ago, when my mother attended a large extended-family reunion. Papa Grande’s (perhaps long-suffering?) American wife, Mama Grande, bore eight children of her own. Though all but their oldest child were born in Merida (two died young), Mama Grande eventually returned to Massachusetts to make sure the Thompson brood got a proper American education.

So whether or not we share DNA, agriculture and food traditions make me feel connected to these Mayan cousins I hope to meet someday. At his crumbling hacienda adjacent to the Chichén Itzá ruins, Papa Grande gave Victoria, Carlos’ mother, a house, from which she ground corn to make the tortillas, roasted squash and beans to feed the up to 100 Mayans farming there and working to dredge the Sacred Cenote, as the Mexicans call it. Many of our Mayan relatives still grow most of their food as subsistence farmers, eking out a living driving taxis for the many tourists who visit the Yucatán Peninsula.

My cousin Elizabeth Sawyer, who is fluent in Spanish, spearheaded a proper Pan-American family reunion with our Mexican relatives in 2006. They even housed her for six months, while she volunteered to teach English to native kids, giving them a leg up for precious jobs in tourism. (Hey, Yucatán’s economy sounds similar to Maine’s.) She felt compelled to give back to the people who had made our ancestor feel so at home.

“His wanderlust just sort of runs in our genes,” Sawyer said of the magical Papa Grande stories that captivated us as kids.

It’s love of the ancient Mayan culture, and more universally, of sharing good, if humble, meals, that binds the Thompson and Marrufo clans together. Our relatives show famous hospitality through food, such as their mild banana leaf tamales steamed in woven baskets over open fires. When my cousins Elizabeth and her mother made arrangements to visit Carlos’ descendants, Janet reported they were told, “We will leave heavier than we begin the trip.”

Perhaps this is why I feel more urgency than ever to finally learn Spanish; I hope to audit a class at Bowdoin College this fall, teaching snippets of the language to my 3-year-old son, Theo, through catchy songs like “Don Alfredo Baila” and the Latino characters Mando and Rosita on Sesame Street. We hope to travel to Merida, perhaps in March 2016, to finally see the limestone pyramids and introduce Theo to any Mexican cousins.

Which brings me, in a very roundabout way, to the tomatillo, which isn’t native to the parched Yucatán but figures centrally in my dad’s Mexican cooking. Diana Kennedy described it to otherwise ignorant Americans as “Mexican green t0matoes” in her landmark “The Cuisines of Mexico” cookbook. It came out in 1972, just as my dad was immersing himself in puerco adobado and carne asada – and Papa Grande’s Peabody Museum collection.

Fresh, husked tomatillos weren’t available then in Massachusetts. They came from a can. As did all the green chiles that Casa Mexico used – Anaheims, poblanos, even jalapeños. For many years, my father assumed such tropical fruits and vegetables couldn’t grow this far north.

So no one’s more excited than he is to see the range of fat, waxy chile peppers now at Maine’s farmers markets. And how sprawling, weedy tomatillos, toppling over with fruit, thrive at his next-door neighbor’s in Belgrade Lakes and in my own neglected plot in Brunswick’s community garden.

But though tomatillos are now ubiquitous here, we shouldn’t take them for granted. Nor can I take for granted the generosity of the Mayan and Mexican people, who aided my great-great-grandfather for so many years.

Papa Grande embodied the spirit of adventure of his time, and also, admittedly, some cultural blindness he shared with other romantic archaeologists of the late-colonial era. His journey had begun in 1879 when he wrote an article for Popular Science Monthly arguing (incorrectly, as it turned out) that Mayan monuments were the remnants of the lost continent of Atlantis.

But whatever his faults, he devoted his life to finding and preserving the carved jade and gold Pre-Columbian artifacts, human sacrifice skulls, the language and religious rituals, of this Mayan civilization. Without his obsessive quest, they might still be lost to history.

And could Papa Grande (who grew up in Worcester, Massachusetts), working in Yucatan in 1900, or even my Dad in Boston in 1970, have ever imagined authentic Mexican food in New England made with tomatillos and chile peppers grown right here? Could they have imagined these items would be so hot on Maine’s culinary scene? That’s delicious progress we can all dig into.

CAMERONES EN SALSA VERDE

The water-loving tomatillo isn’t native to the Yucatán or Yucatecan cuisine; Mayan campesinos didn’t cultivate it during my great-great-grandfather’s 40 years there excavating the Sacred Well. But tomatillos, albeit from a can, were staples of the enchiladas verdes sauce that my father learned to make at the Casa Mexico in Cambridge, Massachusetts in the early 1970s. We also use the creamy salsa verde over enchiladas. This dish has several components. My family never measures the spices, instead adding them freely to suit individual preferences.

SALSA VERDE:

3 large green chiles, preferably Anaheim

1 jalapeno pepper

Vegetable oil

1 large onion, chopped

1 pound tomatillos, chopped

2 to 4 cloves minced garlic

1 to 2 teaspoons fresh or dried oregano

2 cups chicken stock, preferably homemade

Salt and pepper, to taste

1 cup sour cream, or to taste

Chopped cilantro

Roast the chile peppers over gas burners or under broiler. Place in a paper bag and seal for about 10 minutes, then slip off charred skins. De-seed the roasted chilies, preserving their juices, according to your spice tolerance.

Heat a small amount of oil in a medium-sized pot until shimmering. Add the onions and sauté until translucent, about 10 minutes. Add the roasted chiles (and their juices), the tomatillos and the spices. Stir for a minute or 2, then add the stock and season the mixture with salt and pepper.

Simmer for 45 minutes, partly covered, then stir in the sour cream and chopped cilantro, pureeing in a blender or with an immersion blender.

MEXICAN RICE:

If you don’t have saffron, you can substitute turmeric for color.

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

2 cups white rice

Salt, to taste

Pinch saffron

1/2 cup red salsa, or to taste

3 cups hot chicken stock or water

Heat the vegetable oil in a pot until shimmering. Sauté the rice in the oil, add salt and saffron, the salsa and half the stock or water. Simmer, uncovered, until the grains absorb the liquid. Add the remaining liquid and more salsa to taste. Cover and let steam until the liquid is absorbed and the rice is fluffy.

TO SERVE:

3 cups Mexican rice (reserve any leftover rice for another use)

1 cup chopped lettuce, such as Romaine

2 cups peeled, steamed shrimp (Maine shrimp if available)

2 cups Casa Mexico salsa verde, warm (any leftover green sauce freezes well)

Sour cream, to taste

Chopped cilantro

Place the rice in the middle of a platter that is deep enough to hold the sauce. Arrange the lettuce around the rice and the shrimp over the rice. Pour on the sauce. Dollop the platter with sour cream and chopped cilantro.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.