OAKLAND — The mid-March sun had climbed well above the horizon by 9 a.m., but on this morning, it wasn’t helping much. Thin clouds filtered the sunshine, the air temperature was 13 degrees, and a brutal, northwest wind was whipping snow across the road.

Inside Mike Tabone’s house, though, conditions were quite different.

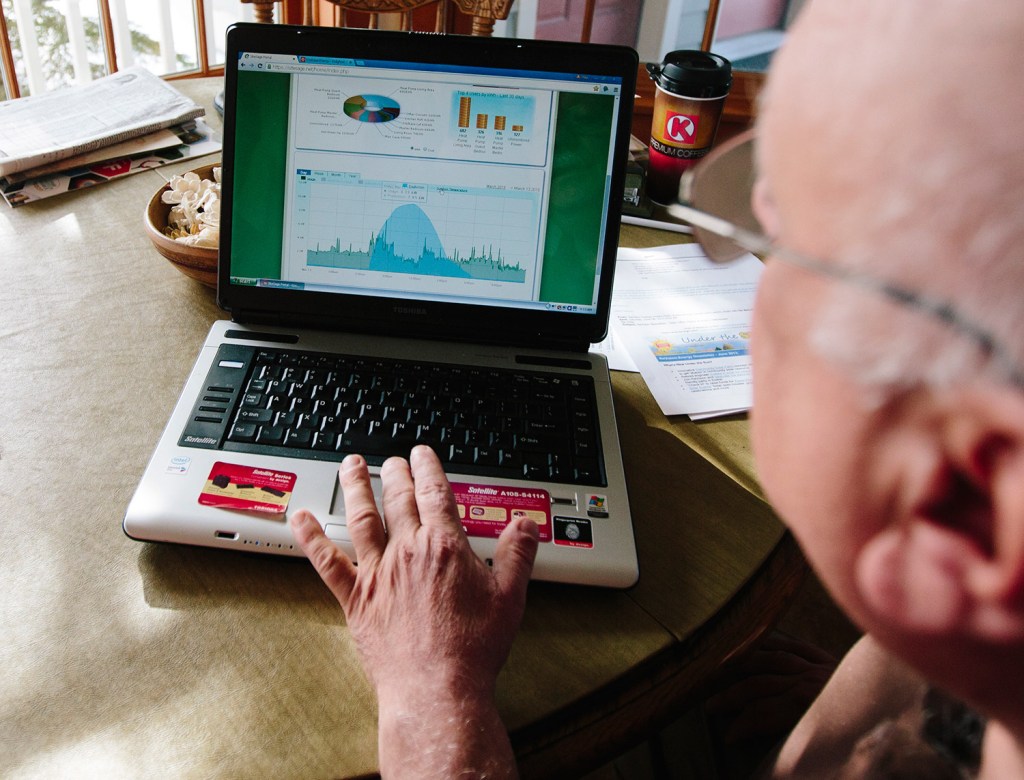

The Fujitsu heat exchanger mounted over the patio doors was wafting 100-degree air from its vents, helping to keep the home comfortable. Most notably, the electricity running the heat exchanger was being generated by 51 solar-electric panels on the roof. A monitoring application on Tabone’s laptop showed the panels were producing more power than was being used, with almost one-third of the output being sent back into the electric grid. As the sun rose higher, it would be possible to feed the hybrid electric water heater in the basement, or charge the Chevy Volt parked in the driveway.

Last year, his bill for heat, hot water and electricity for the year added up to $283.95. He compares that to his oil bill – $3,390 – and electric bill – $1,512 – from the prior year to estimate the payback on his solar investment.

In a state where seven of 10 homes rely on at least some oil heat and virtually all cars run on petroleum, Mike Tabone’s house offers a glimpse of Maine’s possible energy future. Recent refinements in heat pump technology, a drop in solar panel prices and the advent of electric cars mean that the average Maine home now can power its lights, heat, hot water and transportation with electricity from the sun.

This isn’t an off-the-grid homestead or a custom-built hobby house for the wealthy. Tabone is a retired engineer. His 8-year-old, Cape-style house is in a rural subdivision west of Waterville. All the equipment is mainstream and readily available.

But this otherwise sunny picture is marred by a couple of clouds.

First, photovoltaic panels, known as PV panels, still aren’t cheap. Tabone invested $34,000, after government rebates, to install a PV system that can satisfy 90 percent of his energy needs. That goal made it twice as expensive as the average home installation, because most Mainers are still buying systems that are designed to supplement, rather than replace, traditional sources of heat and power. Even so, at today’s oil and electric rates, Tabone figures he’ll pay off the investment in seven years.

Second, New England’s electric grid isn’t set up now for a future with homes like Mike Tabone’s.

PV systems in New England tend to produce more power than needed in the summer and not enough in the winter. The prospect of thousands of homes and businesses cranking out kilowatts when it’s sunny, but needing instantaneous jolts at night or during a snowstorm, presents a challenge to the region’s grid operator.

This changing world has kicked off regionwide debate over how to integrate solar, wind and other renewables onto the grid, and reduce New England’s dependence on oil and natural gas. The discussion also is happening in Maine, where the Legislature will consider bills this spring aimed at creating financial incentives for solar power.

Tabone’s decisions weren’t driven by a passion for clean energy. He and his wife wanted to be more self-reliant in their home and less exposed to the financial impact of volatile energy bills.

“As a retired couple looking to survive for the next 20 years, this move was important,” he said. “I’m not a greenie by any means. But I now have a higher respect for the universe. I didn’t realize how much energy was in that sun.”

MONITORING THE SYSTEM

Tabone keeps a closer accounting of the sun’s energy potential than most people.

An application on his laptop allows him to slice and dice data by the year or the minute. He can see hourly and seasonal trends in solar output. A dashboard shows how much power is being produced by which panels, how much is being used by which appliances and circuits and how much is being sent to the grid. As a footnote, messages tell him how much electricity his clothes washer used in the past 15 days, for example, how many loads were done, and how that compares to the past 60 days.

On this day at 9 a.m., the system was generating 4,939 watts and the house was using 3,458 watts, mostly for the heat pump in the living room. An hour later, output had reached 8,549 watts and usage was 2,227 watts. That’s good, considering not all solar panels were on the job. Crusty snow on the porch roof was covering some panels. On a full-sun day with no obstructions, total output is rated at 12,000 watts.

The solar output is enough to charge Tabone’s gas-electric Volt, which cost roughly $34,000 with rebates. It’s pricey, he says, but similar to a loaded Toyota Camry. And he loves driving the car.

He also loves getting his Central Maine Power bill. It shows how many kilowatt hours he generated and how many he has credited in the “bank.” Under Maine law, utilities pay small-scale renewable generators for their output and charge them an equal rate when they need electricity. The arrangement is called net-metering. Overall, Tabone can meet roughly 30 percent of his household energy needs in the winter. He generates 300 percent more than he needs in summer.

Utilities don’t like the current net-metering rules because, they say, it shifts the cost of maintaining 24/7 service to solar homes to other customers. It’s not a big deal today, when a small fraction of New England’s power is from solar. Central Maine Power reports that it has 1,273 homes and 150 commercial customers with solar arrays.

EXPECTING MORE SOLAR POWER

But the numbers are growing. Last month, Maine Audubon Society in Falmouth and Laudholm Farm at the Wells Natural Estuarine Research Reserve flipped the switch on systems that will meet 80 and 100 percent of their electric needs, respectively.

ISO New England, the regional grid operator, estimates that New England had about 50 megawatts of PV output installed in 2010. The total shot up to 900 megawatts last year, and is expected to double by 2023. That 1,800 megawatts could account for 13 percent of energy during certain hours, the ISO says, or 2 percent of New England’s net load. But it’s just an educated guess, because most small generators are connected directly to local utilities and not the regional grid, so they’re hard to count.

And because solar energy is intermittent, the ISO has to plan for those moments when clouds move in. That will mean keeping more natural gas-fired generators in reserve, it says, so they can start up quickly to plug any power gap.

The ISO’s comments suggest the benefits of solar are very time-sensitive. Solar advocates have highlighted a recent study for the Maine Public Utilities Commission that found solar could have a high value in feeding the grid on summer afternoons, when air conditioning pushes demand to a peak. But in its 2015 Regional Electricity Output report, the ISO puts a finer point on the concept: “Widespread use of solar power will likely shift peak net load to later in the afternoon, just as output diminishes with the setting sun.”

Clean-energy supporters, though, have a different take. One regional advocacy group with an office in Maine, the Acadia Center, is promoting a consumer-focused grid. In its recently released UtilityVision plan, the group lays out details of how to adjust rates to reward electric customers who make specific contributions to operating the grid. One example is to compensate homeowners with PV panels oriented for maximum production at certain times – tilted toward the horizon in winter and set flatter in summer.

These challenges and opportunities are recognized by the solar industry. They were discussed at a March conference in Boston put on by the Northeast Sustainable Energy Association, in a forum on “Rethinking the Grid.” It’s all part of the evolution of the 21st century electrical grid, in which some see a shift from large power plants and massive transmission lines to smaller, more-localized generators using renewable resources.

ADVANCES IN ENERGY STORAGE

Some homeowners will simply disconnect from the grid, but a mainstream transition can’t really happen without better ways to store the on-again, off-again power of the wind and sun. That day may be coming, with advances in lithium-ion batteries, and refinements in competing technologies.

IHS Inc., the global research firm, recently predicted that 9 percent of new PV systems in North America will include energy storage in 2018. The trend is being led by commercial installations in California and other places where high utility rates during peak periods, called demand charges, make expensive batteries economical. SolarCity, the country’s biggest solar PV installer, and Tesla Motors, the country’s biggest electric vehicle maker, have teamed up to put batteries at businesses with PV systems. Tesla, which is building the world’s largest battery factory in Nevada, is expected to roll out a new product shortly, which some observers say will be an energy storage system scaled for the home.

Advanced storage is too expensive now for most homes. But it’s an appealing idea to Mike Tabone. Standing by the electric circuit panel in his basement, he pointed to a spot along the wall where a battery bank could live.

Energy storage aside, Tabone’s home stands as a showcase for where Maine may be heading.

ReVision Energy in Portland installed the PV system. Fortunat Mueller, a co-founder at the company, said the pace of change hinges in part on the cost and acceptance of electric cars and growth of charging stations in a rural state.

But Mueller, who drives a Ford C-Max Energi hybrid plug-in car, agreed that solar’s future is tied to a complex combination of changes in the market and utility rules, such as lower rates at night for charging electric vehicles.

“You can’t just add solar with your eyes closed and that’s your only solution,” he said. “But the handwringing that we’re going to be victims of our own success seems a bit premature in New England, and wildly premature in Maine.”

Correction: This story was updated at 7:09 p.m. on Monday, April 6 to indicate that Laudholm Farm at the Wells Natural Estuarine Research Reserve gets 100 percent of its electricity from solar power.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.