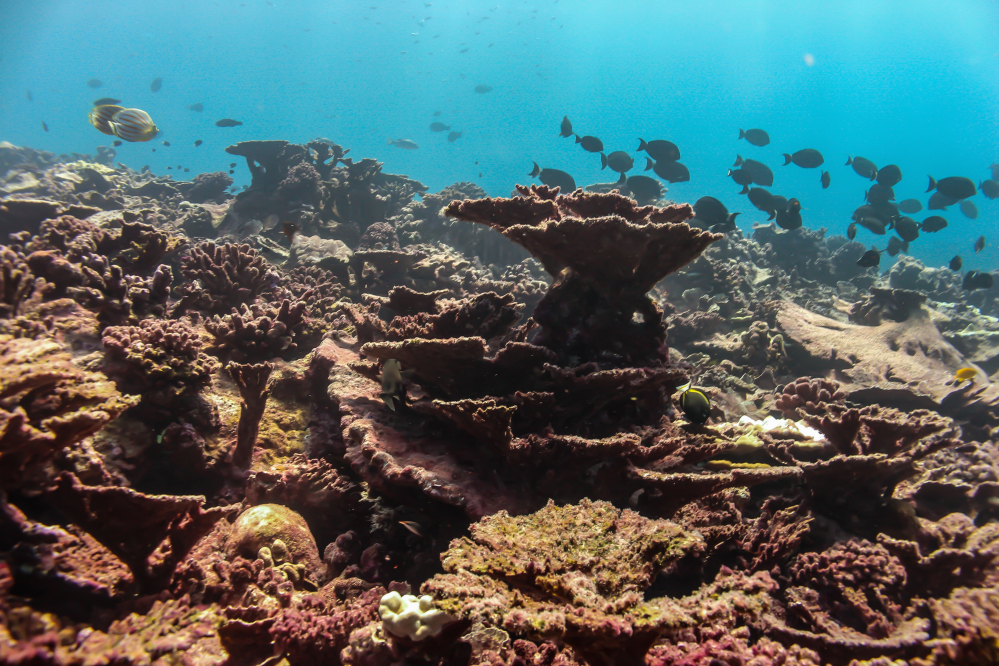

PICKLES REEF, Fla. — Twenty feet under water, Nature Conservancy biologist Jennifer Stein swims over to several large corals and pulls several laminated cards from her dive belt.

“Disease,” reads one, as she gestures to a coral that exhibits white splotches. “Recent mortality,” reads another card. Along the miles of coral reef off the Florida Keys, Stein and her fellow divers have found countless examples of this essential form of ocean life facing sickness and death.

The pattern of decay is shaping up as one of the sharpest impacts of climate change in the continental United States – and a direct threat to economic activity in the Keys, a haven for diving, fishing and coastal tourism.

The debate over climate change is often framed as one that pits jobs against the need to protect the planet for future generations. In deciding to exit the Paris climate agreement and roll back domestic environmental regulations, the Trump administration said it was working to protect jobs.

But what is happening here – as the warming of the sea devastates the coral reef – is a stark example of how rising temperatures can threaten existing economies.

The 113-mile-long Overseas Highway between the mainland and Key West – linking islands that themselves emerged from an ancient coral archipelago – is lined with marinas, bait and tackle shops and an abundance of seafood restaurants.

From the visitors who fill dive charters out of Key Largo to the local fishing industry’s catches of spiny lobsters, grouper, snapper and other species, nearly everything in the Florida Keys is tied in some way to the reefs.

Beyond the diving, snorkeling, fishing and sightseeing, virtually every tourist activity will be harmed if the reefs continue to suffer damage.

Cece Roycraft and a partner own the Dive Key West shop, which sells scuba gear and runs boat charters. Their operation depends on a healthy reef system, because divers naturally are not as interested in exploring dead or damaged reefs, which do not attract as many fish and can be covered in algae. It is an economic reality accepted by residents of the Keys but not yet widely recognized by other Americans, she said.

“It’s equal to the Yellowstone Park, OK?” said Roycraft, who worked to help create a federal program that certifies vessels that train their crews in proper coral protection practices, including following proper mooring rules and ensuring that divers do not poke and prod the reefs.

Tourism “is the economic engine of the Florida Keys. There is no other way for people to make money,” Roycraft said.

Three and a half million people visit the Keys each year – nearly 47 for each of the area’s 75,000 full-time residents. Tourism supplies 54 percent of all island jobs and fuels a $2.7 billion economy, according to Monroe County, which includes the Keys and a significant portion of Everglades National Park.

The importance attached to the reef system defies the usual political divides. Here in the Keys, people voted 51 percent to 44 percent in favor of Donald Trump in the presidential election – but they seem to differ from the president in their support for government-funded programs to protect the environment.

In March, amid fears that the administration might try to defund Environmental Protection Agency programs that protect the reef system, Monroe County’s board of commissioners called for sustaining the EPA’s role and declared in a board resolution that “a healthy marine environment is essential and the most important contributor to the economy of the Florida Keys.”

The EPA’s South Florida program, which received $ 1.7 million in federal funds in fiscal 2017, conducts coral surveys, studies of the health of sea grasses and carries out more-general water- quality assessments. Trump’s proposed 2018 federal budget seeks to eliminate the allocation.

In recent years, the islands have spent millions of dollars, including some federal money, to convert to central sewer systems, ending the damaging practice of allowing human waste to seep into the ocean from septic tanks.

But what is coming into focus is that the threats to the reef system cannot be countered locally.

Ecologists describe the 360-mile-long Florida Reef Tract as a global treasure. It is the world’s third-largest barrier reef, although much less famous than Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

But less than 10 percent of the reef system is now covered with living coral. Scientists anticipate that as early as 2020, it could be in line for almost yearly bleaching events, in which heat stresses upend the metabolism of corals, in some cases killing them. The reefs experienced back-to-back major bleaching events in 2014 and 2015.

An influential 2016 study in the journal Scientific Reports found that coral declines were just as likely to occur in remote, pristine reefs, such as the northern sector of the Great Barrier Reef, as they were to occur in non-remote reefs, such as the Florida Reef Tract. That is despite the fact that reefs closer to human communities probably experience a lot more pollution, overfishing and poor water quality.

The researchers suggested that the main reason for a decline of coral was a uniform global cause – warming.

“It’s not only me feeling compassion for the actual coral, but for the entire ecosystem and how that’s going to affect it in the years to come, unforeseen things that we just don’t know are going to happen,” Stein said after the dive. “It’s frustrating and sad at the same time.”

In the Keys, longtime residents say there’s just no parallel between the reef of today – which still impresses inexperienced tourist divers – and what locals saw decades ago.

Mimi Stafford is a Key West-based master of all trades – commercial fishing, massage therapy, marine biology – who has lived here for decades. Over that time, the ocean has swallowed 25 feet of beach in front of her home, where iguanas thrash through the mangroves and military jets blast by regularly from nearby Naval Air Station Key West.

“When I was a child in the ’60s, the water was so clear I used to think of it as being Coke bottle blue,” said Stafford, citing the colored glass some Coke bottlers used. “And the reef was so healthy, all the coral was very alive. I don’t recall even thinking about bleaching or coral death or coral diseases back then.”

For most, those worries didn’t arrive until the late 1990s.

The threat of climate change to coral reefs first garnered major attention during the strong El Niño event of 1997-98, which triggered widespread bleaching and coral death around the world. The topic has become even more urgent amid an even-worse global bleaching event that began in 2014 and may be winding down only now.

The unrelenting ocean heat in 2014 and 2015 caused many of Florida’s corals to turn white and lose key metabolic functions from heat stress.

The heat episodes in 1997-98 and in more recent years “have been the worst events on record for bleaching events and have had devastating effects and losses of coral cover,” said Rob Ruzicka, who heads the coral research program at Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Research Institute.

Florida enjoyed a respite last year, but the reef system still suffered from a protracted outbreak of deadly diseases that often follow bleaching.

“This is different in that the extent and number of species of corals that have been affected have been dramatic,” said Esther Peters, a coral reef ecologist at George Mason University in Virginia. Twenty-one coral species in the Florida Reef Tract are suffering from multiple diseases, according to reef surveys by the Nature Conservancy. Seven of those species are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, among them staghorn and elkhorn corals.

A 2017 study led by the Nature Conservancy’s senior marine scientist, Mark Spalding, estimated that coral reefs are worth $36 billion annually to tourism industries in key tropical coastal regions such as Florida and Hawaii, the Queensland coast in Australia and the coast of Kenya on the Indian Ocean.

Research from the World Resources Institute has found that 94 countries rely on reefs for tourism and that in 23 of them, tourism related to reefs provides more than 15 percent of gross domestic product.

Back in the Keys, scientists are trying radical new approaches to restoring the reefs.

Twenty feet under water at Pickles Reef, the Coral Restoration Foundation, based in Key Largo, has implanted endangered staghorn corals across the reef.

The implants, raised in undersea nurseries, are small but are growing steadily.

“A little piece the size of your pinkie can grow to be a piece the size of the diameter of a grapefruit in just six months on one of those trees,” said Kayla Ripple, the foundation’s science program manager, referring to the submerged PVC frames from which coral fragments are suspended to grow. “And after six months, we can take them to the reef.”

The question now is whether these reefs will stand up to climate change – and whether experimental solutions such as the restoration approach or global strategies such as the Paris climate agreement can make enough of a dent in time.

“My children saw it right before it really started to decline,” said Mimi Stafford. “But you know, I don’t think their children will unless we can do something.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.