It is a scientific measurement: 350 parts per million.

Now 350 has become the organizing symbol for a global social movement, and its power was on display a week ago in Portland.

Despite bitter cold, more than 1,400 people converged on the city from across New England and eastern Canada. They came to protest the threat of a spill from a thick form of petroleum that might someday be pumped through a pipeline that runs from Portland to Montreal.

But this rally wasn’t just about a pipeline. At its root is a scientific calculation that the world must lower the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to 350 parts per million, or suffer stronger storms, droughts and other extreme weather events associated with climate change. The rally was orchestrated by the people behind 350.org, a website devoted to climate change.

In North America, public attention is focused on tar sands deposits in the province of Alberta. These deposits give Canada the world’s second-largest petroleum reserves, behind Saudi Arabia. But environmentalists say full development will release enough CO2 to push the Earth’s atmosphere past a “tipping point,” making 350 parts per million an impossible goal.

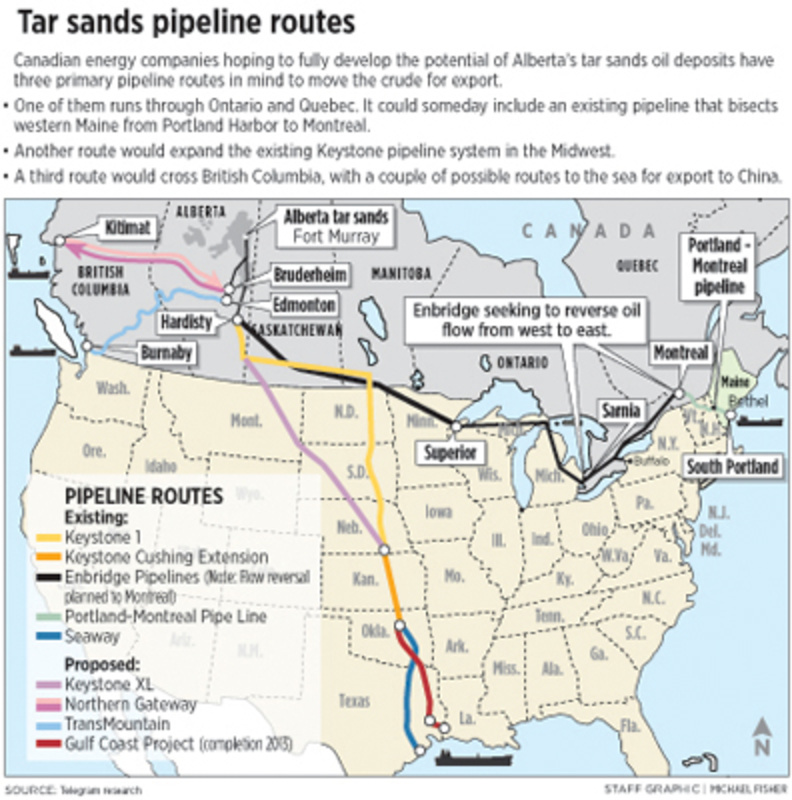

To keep tar sands oil in the ground, activists have launched a coordinated, two-nation effort to block three primary routes in which energy companies want to build or repurpose pipelines. No pipelines, the activists reason, no tar sands oil. One of the routes runs through Ontario to Montreal, and potentially to Portland — the end of the pipeline.

That’s why Portland became a New England focal point Jan. 26, with a rally that drew the largest turnout during a “Day of Action” in communities including Toronto, Montreal and Burlington, Vt.

Portland also served as a preview to what’s being billed as the biggest climate rally in history, on Feb. 17, in Washington, D.C.

Over the next two weeks, using the telephone, email, social media and personal contacts, organizers of the 350 movement in Maine and their allies will work to get as many Mainers as they can to the Forward on Climate rally at the nation’s capital.

But John Quinn, the executive director of the Boston-based New England Petroleum Council, said these events don’t signal to him that momentum is building in the United States to oppose tar sands development. Quinn was in Maine last week along with a representative of Canada’s consul general to New England, to attend meetings in Windham and Bethel, where environmental activists are seeking local resolutions to oppose tar-sands oil.

Policymakers, Quinn said, should be aware that Canada already supplies a quarter of U.S. crude oil and is a crucial partner in a shared goal of North American energy independence.

“If we have a choice between oil from Iraq or Canada,” he said, “I hope we come down on Canada.”

Quinn also noted that up to 70 percent of Maine’s gasoline supply comes from the Irving Oil refinery in New Brunswick. A “significant,” although unspecified, amount of the crude now is shipped by rail from Alberta’s tar sands, he added.

Quinn declined to comment on the 350-parts-per-million benchmark, saying he doesn’t understand the science well enough to have an informed opinion.

“I accept the fact that that’s what they believe,” he said.

ACTIVISTS: ‘TAR SANDS = GAME OVER’

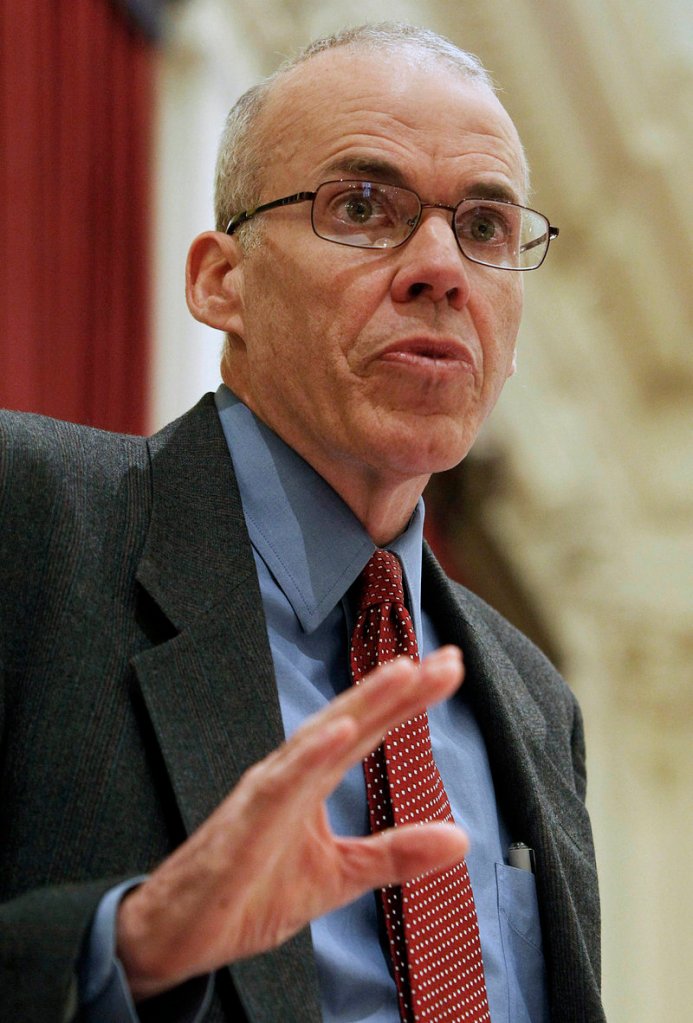

The 350 figure stems from an estimate by climate scientists, including NASA’s James Hansen. They say that two centuries ago, before the Industrial Revolution, atmospheric carbon dioxide was roughly 277 parts per million. Now it’s 392 parts per million and rising. To get back to 350, the world needs to burn less coal and oil, and not dig up Canada’s tar sands, which Hansen considers one of the dirtiest, most carbon-intensive fuels on Earth.

The projection by Hansen, head of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, contains an apocalyptic message for his followers. It’s summed up in protest signs, including those carried by some of the marchers in Portland late last month: “Tar Sands = Game Over!”

In Maine, the fight over tar sands has centered on the Portland-Montreal Pipe Line, which pumps crude oil from ships in Portland Harbor to Montreal.

Last year, Toronto-based Enbridge Inc. filed for permits in Canada to reverse the flow of a pipeline from Ontario to Montreal. The stated goal is to bring tar sands oil east to refineries in Quebec. That would allow Quebec refineries to receive crude oil from Alberta. It also would lessen refinery needs for more costly overseas imports, which have moved through Maine since 1941 over the twin, parallel pipe system.

This shifting market away from imports is hurting business in Portland, where one of the two pipelines isn’t currently being used. Environmental activists on both sides of the border suspect the next step is to reverse the flow on the Portland line, to export tar sands oil overseas, rather than import oil to Montreal.

The company has repeatedly said it has no current plans to do this. But in recent interviews, it has acknowledged a desire to reverse the flow, if it made business sense.

“They’re looking for ways to maximize use of their asset, and that could involve a reversal, if there’s market demand to do that,” said Ted O’Meara, a spokesman for the company.

O’Meara suggested that a line reversal wouldn’t automatically mean the export oil would come from the Alberta tar sands. He was unable, however, to say what other sources might be available.

Activists are using that uncertainty to sow the seeds of distrust. They also cite evidence that tar sands oil is more corrosive and more likely to result in pipeline leaks, a charge the industry denies but one that is being studied by the National Academy of Sciences.

The specter of a highly polluting oil leaking into Sebago Lake, the Androscoggin River or other senstitive locations along the Portland-Montreal Pipe Line has made Maine and Portland regional focal points in an international battle.

The global movement operates under an umbrella organization called 350.org. It functions largely online, and carries out activities through local and regional affiliates around the world. Tactics pioneered in the 1960s anti-war era have been freshened by lessons from the Occupy movement and growing use of social media.

‘AN UNBELIEVABLE TURNOUT’

The Portland rally was organized by 350 New England and state affiliates that include 350 Maine. Representatives meeting in Boston last November agreed that the pipeline would be the region’s rallying point.

“We realized we needed to do something big, and people said, ‘We need to go to Portland,’ ” said Bob Klotz, a South Portland physician assistant who’s active in 350 Maine.

Klotz set out to alert people to the upcoming protest. He started with a personal email list containing roughly 10 names. A mailing list from the Occupy Maine movement eventually expanded his contacts to 1,000 names. An Internet petition he started opposing a resolution last year by the Maine Legislature in favor of a tar-sands pipeline in the Midwest attracted 2,500 signatures on the SignOn.com website, so he sent a general message to those people.

Klotz also learned that Bill McKibben, the author and environmentalist who founded 350.org, was bringing his “Do the Math” tour to Boston. He started another online petition asking McKibben to visit Portland. Five hundred people responded, and McKibben made his climate-change math presentation to a sold-out house at the State Theatre in November. That built interest in the upcoming march.

Organizers were expecting 1,000 people, tops. They were surprised when police estimates put the crowd at more than 1,400. Organizers have since figured that half the marchers came from out of state, some arriving in four buses from Massachusetts and one from Vermont.

Also on hand were speakers and participants from north of the border, including the Greenpeace Canada and Equiterre, a Quebec-based social activists’ group.

“We were really pleased to see such an unbelievable turnout in Portland,” said Adam Scott, climate and energy program manager at Environmental Defence in Toronto. “Many Canadians were very surprised to see such a reaction in Portland. I think it gives a lot of energy to what’s happening here.”

Scott’s group helped organize Day of Action protests at eight locations along the Enbridge pipeline route in Ontario and Quebec. It hosted a question-and-answer session on Twitter that day to build support.

“They can’t expand tar sands without these pipelines,” Scott said. “It’s critical for them to have this infrastructure. Stopping these pipelines will have a measurable effort on greenhouse gas levels.”

MAINE CONNECTIONS

Canadian activists also keep in contact with mainstream environmental groups in Maine that were instrumental in building support through the pipeline issue. They include Environment Maine, the Maine chapter of the Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Council of Maine.

NRCM last year organized rallies and meetings in Casco, Bethel, Raymond and South Portland, one to mark an anniversary of a major leak of tar-sands oil from an Enbridge pipeline into the Kalamazoo River in Michigan in July 2010. Climate change is the overarching issue, but worries that include the potential for a pipeline leak to pollute drinking water from Sebago Lake or clam flats in Casco Bay brought out hundreds of people.

“I wouldn’t want anyone to dismiss these as local concerns,” said Dylan Voorhees, the NRCM’s clean energy director. “There are a variety of motivations.”

Maine groups are keeping the issue in the public eye by helping to introduce local resolutions aimed at rejecting the use of tar sands oil. They have made presentations in Portland, Windham and Bethel, with other communities pending. In Vermont, 23 towns have put tar sands transport resolutions on their town meeting agendas.

WASHINGTON RALLY PLANNED

Now mainstream groups are turning their attention to the Washington rally on Feb. 17. It is being organized by 350.org, the Sierra Club and the Hip Hop Caucus, a national human rights group aimed at young people.

Much of the organizing is taking place online. People posting on the NRCM’s Facebook page are asking about buses from Maine. The Maine chapter of the Sierra Club has an RSVP sign-up on its website for people who want a bus ride. The official logo for the Forward on Climate event integrates a Web address but also a Twitter symbol to link with information and tweets from participants, including McKibben. The hashtag is #noKXL.

The KXL is a reference to the Keystone XL pipeline. This proposed pipeline through Montana, South Dakota and Nebraska would greatly expand the ability of tar sands oil to be produced and exported.

Oil industry and labor groups are pushing for President Obama to approve Keystone XL this year, saying thousands of jobs and North America’s energy independence hangs in the balance.

Keystone XL signifies one major route from Alberta for tar sands oil. Another direction, west to British Columbia for export to China, is being opposed by Canadian activists and indigenous people.

The Feb. 17 rally is designed to show Obama the depth of opposition to Keystone XL. Some opponents say they are encouraged by the president’s statement during his inauguration: “We will respond to the threat of climate change, knowing that the failure to do so would betray our children and future generations.”

The president’s comments resonate with Becky Halbrook of Phippsburg. A retired corporate lawyer, she has two grandchildren. In her view, petroleum today is similar to how tobacco was viewed years ago: People still use it and make money from it, but new evidence shows grave risks and it’s time to kick the habit.

Halbrook says she has been inspired by Hansen’s 350 calculation. She feels strongly enough about the threat of climate change that she went to Washington, D.C., two years ago, for an earlier Keystone XL protest. It was a call for civil disobedience at the White House, and she was arrested along with 54 other people.

Halbrook went to the Portland rally and is making plans for Washington. The size of the crowd and robust media coverage, she says, are crucial to encouraging policymakers to block the pipelines and, in turn, put a lid on climate change.

“This isn’t simply a matter of ‘not in my backyard,’ ” she said. “It’s more than just a pipeline leaking into a river.”

Staff Writer Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.