Sharon Lockhart’s “Lunch Break” at the Colby College Museum of Art has the look and feel of a major exhibition: video installations, photography, curated works by other artists, outsider art and, yes, lunchboxes.

The show is the result of a year Lockhart spent photographing and observing the workaday culture at Bath Iron Works. She includes several dozen pieces from Colby’s collection and Maine historical museums alongside her own photographic work.

You first encounter the elegantly austere structure for a video installation (Lockhart collaborates with a talented pair of architects for her exhibitions). The video, “Lunch Break,” is tremendous, an 80-minute slow-motion glide down a seemingly interminable assembly hall running through the guts of BIW. You can feel the throbbing rumble of the machine-noise soundtrack as though time itself is grinding to a halt. Workers are perched and seated while on break, so frozen in time they hardly move.

The second room features photos of “independent businesses” (some of which can be seen in the video) where BIW workers sell coffee, doughnuts, candy and snacks to each other on the honor system. These tend to be homemade and lockable wooden boxes with coffee makers (50 cents a cup), hand-scrawled price lists and names like John’s Java Hut, Handley’s Snack Shop and Dirty Don’s Delicious Dogs. The large C prints read like snapshots but maintain an unflinching eye for detail.

The Lunder Collection’s great Duane Hanson sculpture of a man playing solitaire sits in the center of the room — so realistic it feels like he is really there with you. Why is the Hanson in Lockhart’s show? Solitaire is a leisure activity, maybe?

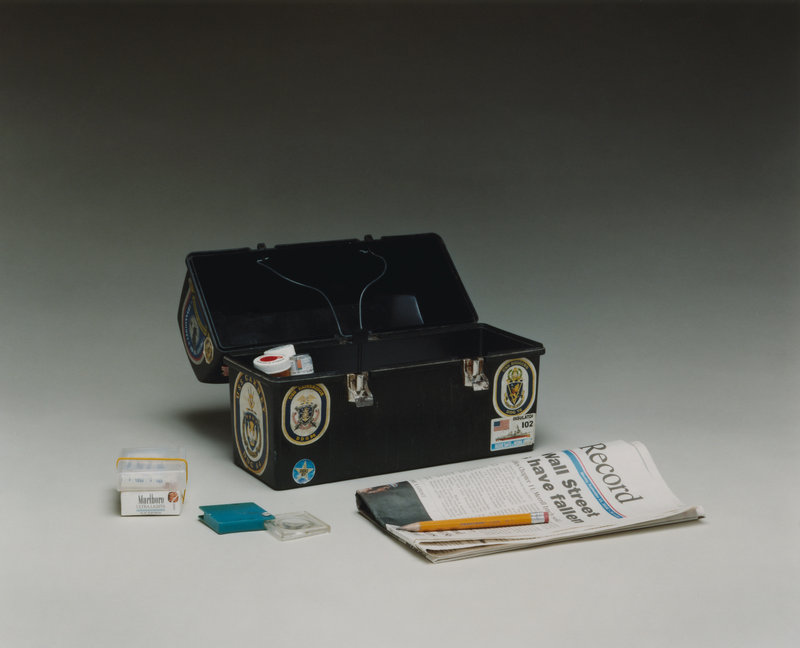

“Lunch Break” also features a series of photographs of lunchboxes (a way, according to Lockhart, of “getting around the conventionality of worker portraits”). Many of them are well-worn coolers covered in stickers with flip-open, handled white lids. Lockhart shot them as large-format product photographs — closed, opened and then unpacked.

One of the most interesting elements of the show is an enormous plinth covered with 16 vitrines. These contain a bewildering range of handmade objects: a leg-shaped 19th-century mackerel plow, scrimshaw dominoes, a tiny Calder sculpture, lunchboxes and other oddities.

Another room features a Rauschenberg piece made of torn cardboard, a Sherrie Levine work in which eight elliptical patches on a sheet of plywood are painted gold, and 13 spruce gum boxes. You know, stuff made of wood.

It becomes clear that Lockhart’s “method” is free association rather than thoughtful conceptual structure: lots of interesting objects presented by a big-deal art world insider accompanied by a newspaper printed for the show — The Lunch Break Times.

Why a newspaper? Because Lockhart noticed many of the workers read newspapers on break — imagine that. Yet in the paper is a comment by Lockhart’s mother: “My daughter now can’t stand to read or touch a newspaper.” So much for solidarity.

I think the respectful tone of The Lunch Break Times accurately mirrors Lockhart’s intentions, but the exhibition is ultimately a monstrous monument to cultural condescension.

A friend from Waterville (a New York art world insider — like me — who was the director of a major Chelsea gallery for seven years) said of Lockhart’s show: “It’s like Columbus discovering America.” Lockhart’s privileged point of view is incredulous: These savages make stuff? They read? They have a sense of aesthetics? Who knew?

You could argue that Lockhart is un-ironically celebrating the local culture of the BIW workers, but then it’s only her transforming and privileged vision that makes it art. I wonder what workers thought when they saw photos of their lunchboxes hung near Rauschenberg’s torn cardboard “painting”?

Yet the subject of the Rauschenberg is the context of the white gallery wall — so the piece quivers with ironic hilarity. Likewise, Lockhart’s works are intended to hang in the Gladstone Gallery in New York’s swanky Chelsea district, where her editioned prints are sold for $20,000 each. I wonder if the workers know that.

I bet most of the workers who saw the show were excited and polite but left scratching their heads — thinking they didn’t understand it because they aren’t art world insiders. But they didn’t understand it because there is nothing to understand: the exhibition has no poignant messaging or conceptual clarity.

Lockhart gets away with this because it feels complex, and she talks it up like it’s chockablock with brilliant ideas. She simply takes advantage of the fact we tend to blame ourselves for not “getting it” — even when there is nothing to get.

Viewing this show is like getting a tour of the MET by an over-caffeinated sprinter with ADHD, but it’s worse because she thinks she’s Jane Goodall, and you’re a chimp.

“Lunch Break” is particularly disappointing because Lockhart really does have a good eye, great chops as an artist and potentially worthy subject matter. But she’s too in love with her own viewpoint to realize she doesn’t understand it in relation to local culture. Local culture is not pretentious — a lesson Lockhart should learn.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.