Colleges come in all shapes and sizes. Some are draped in ivy; others with paint peeling from their walls. Among the latter is Maine’s University College of Bangor, a repurposed military base that’s said to be the poorest college in the nation.

While these stats may not lure many teachers to its ranks, others, like biology professor and author Robert Klose, consider the perks. The upside of neglect is that Klose is left alone to teach, muse and write.

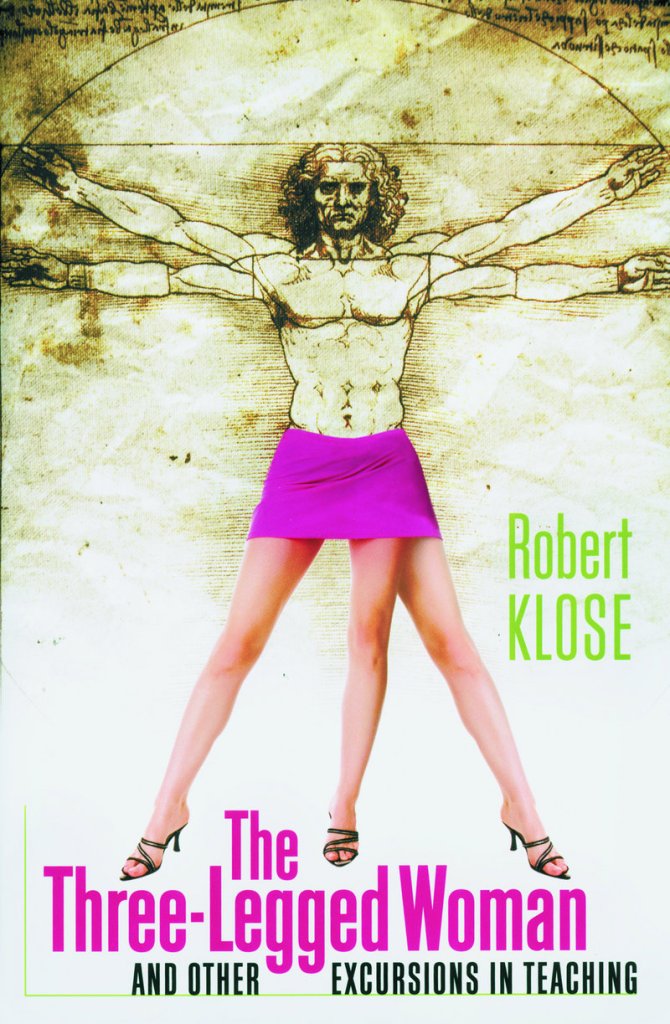

At this downmarket college, an open admissions policy supplies all the plot, character and motive a storyteller could want. Klose’s enrollees, none of them science majors, include all manner of “non-traditional students” — a cop, a single mother of two, even a convicted killer on release from prison to attend his class. This unlikely mix fuels the author’s incisive and droll new book, “The Three-Legged Woman and Other Excursions in Teaching.”

Over the course of some three dozen essays, Klose mounts a good news/bad news campaign on the state of higher education. The bad news is the surfeit of evidence confirming one’s worst fears about what’s going on in the classroom.

Those students who type fast and furiously on their laptops to keep up with the lecture?

Some, as Klose painfully learns, are actually clicking on nude photos. Others, untrained in note taking, attempt to transcribe every word and mangle their meaning in the process.

Nor is such cluelessness reserved for the classroom. Klose stops in the hallway to talk with a young woman who’s composing poetry in a notebook. When he asks whether she’s read Robert Frost, the student pauses and says, “No. Who is he?”

The good news is that Klose, now in his third decade at the college, has survived these and other affronts, and is here to tell the story. In these essays, he takes on all sorts of maddening conduct — texting in class, lateness in its myriad forms, and the often florid excuses that students invent to cover their errant ways.

Then, too, as a biology professor, Klose routinely confronts the “E”-word. Each semester when he teaches evolution, there’s invariably some student who bristles or walks out of class. He deals with these cases gingerly, careful to differentiate among politics, religion and science.

Like any educator, Klose has his pet peeves, which transcend the particulars of any one college. He writes eloquently on the collateral damage that results when young people can’t be bothered to read or write.

“Students project the sense that as long as they are making themselves understood, all is well,” he says. “Sort of like driving a junker that blows smoke and has a flat tire: If it gets you there, what’s the problem?”

Still, many of these essays, and the author’s forte, are stories about ordinary people going about their lives.

We meet Jason, a student who’s there because his dad insisted that he go to college. When he fails his first biology test, Klose asks him to come by the office for a chat. We learn that Jason is miserable in school, but loves working with plants.

Klose seizes on this detail and advises him to drop out and go to work for a landscaper.

“As it turned out — before Jason got religion and pursued his passion for petunias — his was a classic case of someone letting college interfere with his education,” Klose says.

Over and over, we see the professor as heretical cheerleader, debunking the universal merits of a college degree in favor of self-knowledge.

Readers of this book may well conclude that Klose is that rare teacher who galvanizes a class.

In several essays, he retraces his own path as a scientist, reanimating the geeky kid with the microscope who was forever exploring the natural world.

This is a man with a passion for science and teaching. Readers will enjoy his wry ponderings on the state of both.

Joan Silverman writes op-eds, essays and book reviews for numerous publications.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story