Central Maine Power Co.’s $1.4 billion transmission system upgrade isn’t designed to handle the power that can be made available at times from new and existing alternative energy plants in northern and eastern Maine, federal utility regulators and the region’s grid operator have determined.

The shortcoming has financial impacts that could discourage future investments in alternative energy in Maine.

In the worst-case scenario, adding these new plants to the system as it’s currently built could create unstable power flows in the grid that could lead to widespread blackouts across New England.

How to solve the problem and what that might cost have yet to be determined.

Considered the largest transmission investment ever in New England, the Maine Power Reliability Project is meant to modernize CMP’s 40-year-old bulk power lines to serve customers for decades to come. The work began in 2010 and is expected to be done in 2015. The cost is being shared among ratepayers across New England.

An important side benefit, CMP has said for years, is that the system would provide the infrastructure to send more power from the state’s growing renewable energy industry to southern New England.

But for projects in northern and eastern Maine, that benefit is now in question, as is perhaps millions of dollars in investment in an area targeted for major wind projects, according to documents reviewed by the Maine Sunday Telegram and interviews with key players in the energy industry.

“It has to cause every developer of a renewable project in Maine to sharpen their pencils,” said Andrew Landry, a Portland lawyer who represents some developers.

The new calculations come after the regional grid operator, ISO-New England, came to a preliminary conclusion that CMP’s interconnection in Orrington has too little capacity to transfer large amounts of power south without risking “stability” problems. That instability could lead to regional blackouts.

In a March order, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission agreed with ISO-New England, saying that some renewable energy developers in Maine misunderstood the benefits of CMP’s project.

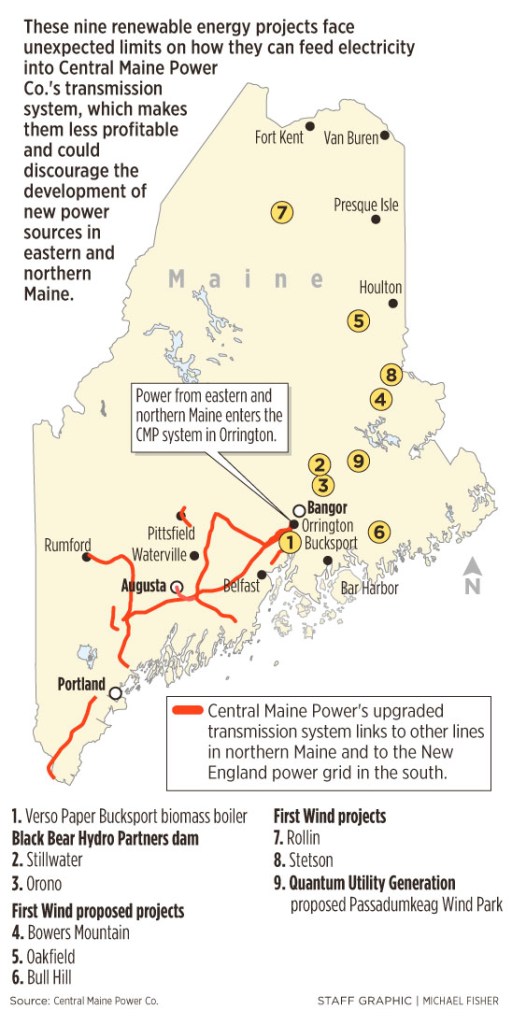

The initial fallout from this determination is that nine renewable power projects in Maine — existing and planned — weren’t able to participate in an annual auction last month for future capacity payments. Generators that qualify for these special payments earn extra money for making power available if it’s needed to meet demand.

Even without these capacity payments, the existing generators are producing power and being paid for it. But capacity payments can be worth millions of dollars, and can make or break a project. They are especially important now, when the renewable energy industry is competing against record-low natural gas prices and facing the potential loss of a coveted federal tax credit in Congress.

It’s not clear yet why the new transmission system can’t do what some Maine power generators and state officials expected, what solutions might be possible, what they might cost and who would pay for them.

The Maine Public Utilities Commission, which approved the transmission project in 2010 after extensive review, is pressing ISO-New England to finish a complex, computer-modeling study meant to explain its stability concerns. The PUC also has asked if there are any “low-cost fixes” that would increase the transfer limits at Orrington.

The problem has caught some renewable energy producers by surprise, according to Jeremy Payne, executive director of the Maine Renewable Energy Association. They were well aware of pre-existing stability issues at Orrington and the need for full testing, but expected that the new system would improve access for their projects. Payne echoed Landry’s view that some new projects may be in jeopardy.

“Any time you take away a revenue stream, it creates concerns,” he said. “It introduces greater uncertainty for all projects.”

CMP is building or upgrading 500 miles of transmission lines and various substations from Orrington to the New Hampshire border in Eliot.

Responding to the issues raised by generators, CMP says the project will meet its primary goal of improving reliability. As a side benefit, it will aid wind developers in western Maine’s mountains, where upgrades will reduce system congestion.

“This is a reliability project,” said John Carroll, CMP’s spokesman. “It was always understood that there were transfer limits (in Orrington), but we weren’t trying to fix that problem.”

After gaining PUC approval in 2010, CMP’s president, Sara Burns, called the project a “state-of-the-art system that will serve the region’s growing renewable energy sector and provide tremendous economic benefits for the state.”

In considering big power lines, regulators weigh two issues: how much power the lines can carry, and the impact of carrying that power on the grid’s stability.

One big improvement CMP is making will increase the system’s “thermal loading,” so the lines can physically handle more power and heat without sagging or melting. But upgrading thermal loading doesn’t solve stability concerns on the rest of the grid.

An initial analysis by ISO-New England, CMP and a consultant working for CMP identified potential for trouble if the system had to handle more than 1,350 megawatts under certain conditions. Transferring the full capacity of existing renewable plants in Maine, plus some generators in New Brunswick, would already exceed that figure.

Utility grids set transfer limits to help maintain a consistent flow of electrons. They rely on safety devices to cut power flow, just like a home’s circuit breaker, if unstable voltages threaten power plants and equipment, such as during high-stress conditions that might take place on a hot summer day. In a worst-case scenario, an unstable power flow in Maine could have a wide-reaching impact.

“One of the effects could be that Connecticut would go dark,” said Tony Buxton, a Portland lawyer who represents large energy users in Maine.

One of Buxton’s clients is Verso Paper Corp. The company is in the midst of overhauling a boiler at its Bucksport paper mill to burn biomass, and sought to qualify it to compete in ISO-New England’s capacity market. But the grid operator performed an initial analysis of connecting the boiler and determined that Verso’s $42 million project wouldn’t qualify because of the transfer limits in Orrington.

That was unwelcome news at Verso. The company already has spent the money, according to Bill Cohen, a company spokesman. The inability to receive capacity payments will have a financial impact, he said, but he wouldn’t say if it would make the project unprofitable.

“We’re hopeful the parties will come together and find a solution,” he said.

Verso’s problem is shared by other Maine projects, according to the Maine PUC. In FERC documents, it noted that the delay had disqualified nine renewable projects from participating in this year’s capacity auction.

Besides Verso, these projects include key ventures by First Wind, the state’s leading wind developer. Among them is one of Maine’s largest windpower proposals, the 150-megawatt Oakfield project in Aroostook County, which won state approvals in January.

Also included is the 60-megawatt Bowers Mountain project in Washington and Penobscot counties, which was rejected last month by state regulators but may be redesigned; and the 34-megawatt Bull Hill project in Hancock County, which has received construction financing.

Also named are existing First Wind projects that send power to the grid, but have not qualified for capacity payments. They include the 60-megawatt Rollins project in Penobscot County and the 83-megawatt Stetson project in Washington County.

First Wind declined the newspaper’s request to comment last week on the issue. But in the filing at FERC, First Wind said ISO-New England’s incomplete analysis isn’t a good reason to disqualify a project.

Other projects that were disqualified last month include existing Black Bear Hydro Partners hydropower projects on the Penobscot River and the proposed Passadumkeag Wind Park in Penobscot County.

ISO-New England argues that if the Orrington interface continues to pose stability problems, transmission upgrades beyond CMP’s project are needed to achieve reliable operation. It also contends that the capacity process isn’t the appropriate way to identify “low-cost fixes” sought by the Maine PUC.

In March, FERC sided with ISO-New England. It agreed with the grid operator’s assessment that Verso, the Maine PUC and First Wind “erred in their understanding of the benefit of the MPRP.”

The FERC commissioners concluded: “As ISO-NE explains, the MPRP was designed to ensure the continued reliability of Maine’s transmission system and its ability to serve load; it was not designed with the purpose or intention of increasing transfer capacity to a level sufficient for the Maine resources to qualify (for capacity payments).”

Staff Writer Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at: tturkel@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story