When the National Civil War Museum in Pennsylvania sought someone with expertise to edit a newly discovered trove of letters from Civil War hero and Maine native Joshua L. Chamberlain, there was little doubt who could do the job.

The museum tapped Tom Desjardin, chief historian for the state of Maine. He has written several books about the Civil War, with an emphasis on Gettysburg, where Chamberlain earned his reputation fending off Confederates at Little Round Top. He has taught history at Bowdoin College, written extensively about Chamberlain, and served as historian at Gettysburg National Military Park.

In addition, Desjardin served as historical adviser to actor Jeff Daniels for his role as Chamberlain in the films “Gettysburg” and “Gods and Generals.” He is also working on a biography of Chamberlain, due out next year. Few people, if any, know more about Chamberlain than “the guy from Maine,” as Desjardin was known among his colleagues at Gettysburg.

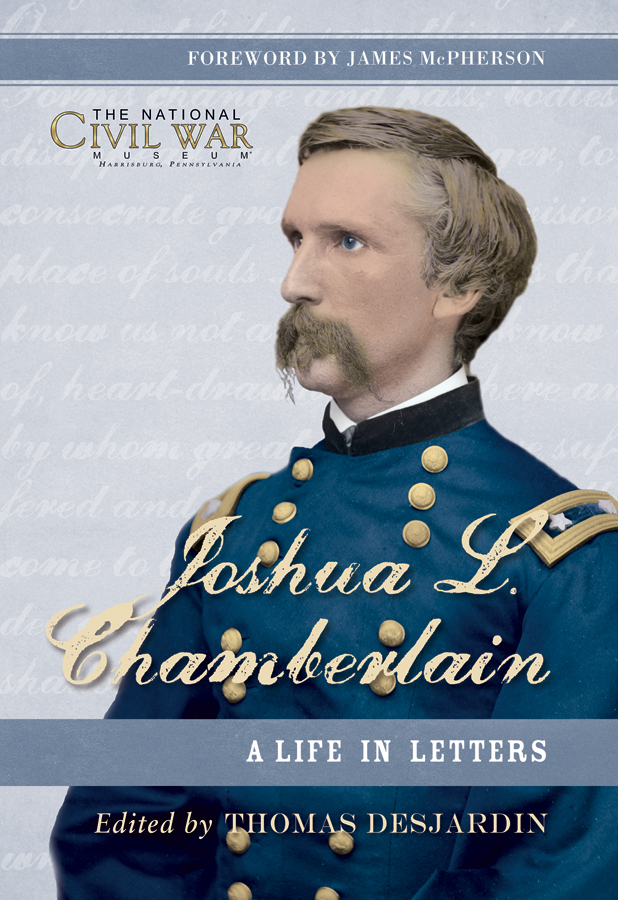

“Joshua L. Chamberlain: A Life in Letters,” was released last month by Osprey Publishing. Desjardin edited the letters and put them in context. The new book unearths almost 300 letters that until now had been held privately.

There are many Chamberlain letters out there, and at least two books have been written about his correspondences. But this batch includes many sent by or to Chamberlain from his college years at Bowdoin in 1852 to his death in 1914. The first 100 include many that reveal a secret, intimate relationship he had with his cousin Annie Adams; another 200 offer insight into his life as a Union commander.

We spoke with Desjardin last week.

Q: Let’s begin with a discussion about these letters. Where did they come from, and why are they just coming to light now?

A: Without going into too much about Chamberlain’s family history, these letters were in the hands of his granddaughter’s in-laws. They were not directly related to him by blood. They were in his granddaughter’s husband’s family. So they were not really descendants. They lived in Connecticut and had these letters. They really did not know who he was or why they had them.

Back in the mid-’90s when the movie “Gettysburg” aired, the family called Civil War artist Don Troiani, who also lived in Connecticut, and said, “We have all these letters. Do you want them?” They sold them to him, and he sold them to the National Civil War Museum in Pennsylvania. They paid more than quarter-million dollars for them and put them in a storage vault. A year and a half ago, they got in touch with me and said they wanted to publish them as a fundraiser for the museum.

Q: What makes this collection significant?

A: There are 270 or so letters, plus a few artifacts. It was an opportunity to get a hold of this big giant cache of information so that people who are really, really interested in Chamblerain could learn more about him. It closes a lot of holes and fills in a lot of blanks. It’s great for those people who pore over every tiny detail of Chamberlain and his life

This is probably the third book of his letters. But the others are in a public collection, and people could have gone to read them. But maybe only a dozen people have read these letters ever, since he wrote them. That is the fun, fun part about it. It’s all new, rare stuff.

Q: You knew a lot about Chamberlain before you began this project. How do you feel your knowledge has been enhanced and expanded with this project? What is the most striking thing you learned about Chamberlain in the course of this project?

A: A lot, actually. Anytime you get a big chunk, there are a lot of little details, but also some major things. A third or so of the letters are between he and his wife, mostly before they were married. In the four or five years of their courtship, there are maybe 100 letters between them. They knew each other for a year or two when he was at Bowdoin. He went to the seminary in Bangor, and she went to Georgia. They were apart for three years. During that time, they wrote back and forth a lot. You go through their emotions and stresses and a lot about their family lives. There was some of that before, but this is a much richer picture.

These letters go through all his life. One letter that jumps out at people is the letter where his mustache is invented. It was invented in 1862. John Marshall Brown was a student of his and in his regiment, and one day he took a pair or scissors and a razor and started to trim his beard. Chamberlain wrote home to his wife and explained it. For the rest of his life, he was known for that mustache. We now know what day it came into being. So there are fun ones like that.

There is another amazing letter of 3,000 words written from the battlefield at Fredericksburg. He took notes on the battlefield, and then within three or four hours, he wrote about it to his wife. It was the first time he had seen combat, and he was in the thick of it. He wrote this long letter to his wife. Fascinating letter.

When he was at the seminary, we always had known he had some kind of relationship with his first cousin, Annie. In this, there are 11 letters from Annie to him, making it very clear they had an intimate relationship for at least a year. Fannie (his wife, Frances) was in Georgia, and he was in the seminary.

Q: What did it feel like to actually handle the letters?

A: It’s fascinating. Reading 19th-century handwriting and language is almost like another language. There are phrases common of the time that we don’t understand. The handwriting wasn’t great and paper was in short supply, and they would turn the page sideways to fill up space. You have to turn and read sideways. It’s inkwell sort of writing. It can be difficult to just read the handwriting, and then pick up the phrases. People who do it, train themselves. They figure out phrases of time periods and the way people spoke to and wrote to each other.

Q: Chamberlain is described by many as a mythical figure. Do you think this volume of letters sharpens that image of him?

A: I hope not. One of the things about my relationship with him, I struggle with people trying to make a saint of him or put him up on a pedestal. Because it robs us of his greatest value. The more human he is, the more we can relate to him. The flaws are important, and the myth-making can often be not a good thing.

When you brush over the flaws and only dwell on the mythological, you don’t get a complete picture. I try to keep him grounded. He was a guy from Brewer. I don’t want him to be sainted or mythological. But there is a ton of that sort of thing. The struggle is to keep him on the ground. These letters are great for that. They are really personable. He was just a guy who was put in these amazingly difficult situations and overcame them.

Q: What do you admire most about him?

A: He had a lot going against him. He had a bad stuttering problem when he was young. He was a nerd, a geek. He talks about it at length. He was quiet, didn’t like to speak to people. He wasn’t very social.

Yet, despite his stuttering problem, he was fluent in seven languages and taught rhetoric at Bowdoin. To come from so many challenges and simple beginnings, he got himself educated and got himself a place in life and achieved some remarkable things. There are a lot of kids in Maine today in that same situation. His life can be an example for them, but not if we turn him into something he wasn’t.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or: bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story