EASTPORT – The tide is running out of Passamaquoddy and Cobscook bays, transforming the miles-wide ocean passages around Eastport into fast-running rivers.

To the east of this easternmost American port, the Western Hemisphere’s largest whirlpool is surging to life, creating a vortex capable of sucking a small skiff into the abyss. Here on the west side of town, the sea is fleeing Cobscook and, unwittingly, generating electricity for the Ocean Renewable Power Co.

Slung beneath a specially built barge moored near the bay’s mouth, a sailboat-sized turbine spins in the 4-knot current, generating a clean, renewable and predictable flow of electricity. It’s a 50-kilowatt prototype that ORPC is developing for use in rivers, a small cousin to the 60-kilowatt device it tested here last year.

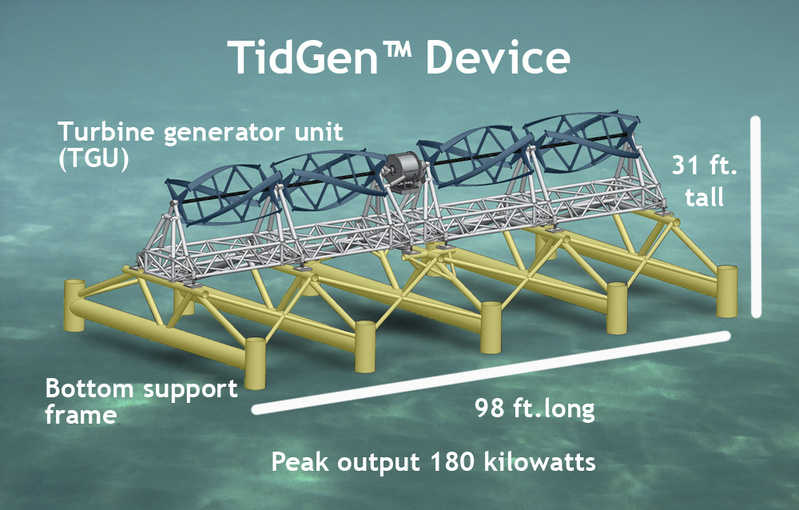

On Tuesday, however, the company will unveil its first full-scale commercial unit at a ceremony here: a cylindrical module as big as a Grand Banks fishing schooner with long curved turbine foils. Sometime next month, it will carefully attach the module to a mount already awaiting it on the Cobscook sea floor a mile farther up the bay from here. The company will attach cables linking it to new transmission lines on the Lubec shore and, with the push of a button, the 180-kilowatt turbine will begin selling power to the grid, the first of a new class of damless tidal energy devices to do so anywhere in North America.

Tidal power, long in development, is finally coming of age, with a Maine company leading the way.

“What ORPC is doing in Cobscook Bay is really a very important milestone,” said Paul Jacobson, an ocean energy expert at the Palo Alto, Calif.-based Electrical Power Research Institute. “With this project, these tidal power devices have finally crossed the threshold into commercial development.”

There’s much more to come. ORPC plans to add two more turbines to its Cobscook site in the coming year, and as many as 18 in the faster, harsher waters of Passamaquoddy Bay on the other side of Eastport by 2016.

“Maine is where it all started and where the lessons are being learned,” said ORPC’s president and co-founder, Chris Sauer, who calls Eastport the “Kitty Hawk” of his nascent industry. “Maine will become the intellectual center for tidal energy, with the people and knowledge base for how to do this.”

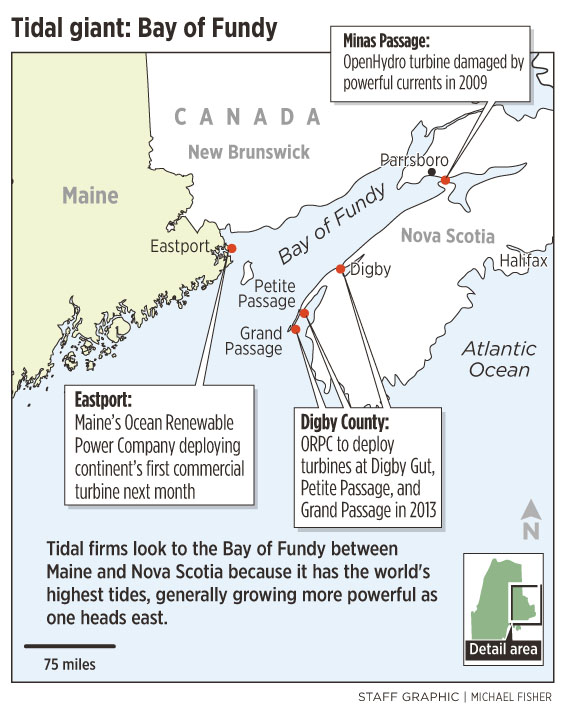

The Eastport area has Maine’s highest tides — 20 feet — because it is perched at the mouth of the vast Bay of Fundy, home to the greatest tides on the planet. It’s the ultimate tidal resource, and ORPC and its foreign rivals are competing to harness its energy.

OPRC turbines are to be deployed next year across the bay in Digby County, Nova Scotia, while Canadian and European competitors are running tests in Minas Passage near the head of the bay, where swift, 50-foot tides have already torn one turbine apart.

It’s perhaps fitting that the industry’s commercial birth is occurring in Eastport. During the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt — who summered in the area — construction started on a massive, old-style tidal project here, one that would have dammed up Cobscook altogether, probably dooming the sardine and scallop fisheries on which the area’s residents depended.

Congress ultimately axed the project for fiscal reasons, though not before a causeway had been built connecting Eastport — previously an island — to the mainland.

Unlike the 1930s project, today’s tidal technologies are inspired by wind turbines and require no dam. The devices are simply mounted on the sea floor, where they slowly spin in the current, out of sight and well beneath the hulls of passing vessels. Tests so far suggest the turbines have no effect on marine life, which appears to have no difficulty detecting and swimming around them.

“This technology we are pursuing doesn’t involve the construction of actual barrages or dams, so it’s much more environmentally sensitive,” said Steven Chalk, U.S. assistant deputy secretary of energy, whose department awarded a $10 million grant to ORPC in 2010. “This technology is less mature than wind or solar, but tides are very predictable, so we know what kind of power we’ll get at a certain time of day and day of the year. That’s an important advantage.”

Five years ago, ORPC was a fledgling startup operating out of an incubator office at the University of Southern Maine’s Center for Enterprise Development, its staff applying for grants and investors to build and test its first prototypes off Eastport. Now it’s hopped ahead of its competitors in North America, including older and larger European companies like Dublin-based OpenHydro and the Siemens-controlled U.K. powerhouse Marine Current Turbines, which has been feeding Northern Ireland’s grid from a huge 1.2-megawatt tidal turbine at Strangford Lough since 2008.

In late 2009, OpenHydro deployed a three-story, 1-megawatt device at the Nova Scotian government’s test site in the Minas Passage, where the tidal current runs at a staggering 12 knots. But the device — which resembled the front of a jet engine fan — had to be pulled up just a few weeks later after its communications devices and many of its fan blades were torn off by the current.

Earlier this year, the company’s Canadian partner, Emera, announced it was abandoning further testing and giving up its berth at the test site.

“We had great learnings coming out of the Minas Basin Project, and one of the learnings was that the tides are much stronger than anyone anticipated,” said Sasha Irving, a spokesperson at Emera, which is the parent company of Bangor Hydro and Nova Scotia Power. “There needs to be another way to test this technology that is faster and doesn’t require full deployments and recoveries.”

Irving Oil, part of the family-owned conglomerate that dominates the economic and political life of New Brunswick, abandoned a $600,000 tidal energy site survey of the Canadian side of Passamaquoddy Bay two years ago due to “policy concerns” and “uncertainty around the true viability of tidal technologies.” (The company didn’t respond to interview requests.)

These developments helped ORPC — which has taken a phased “walk before you run” approach — to win the North American race to commercialization, a big advantage in efforts to scale up and spread.

“There are very few technology providers internationally that have installed machines and have had them running for a significant amount of time, and ORPC is leading in that charge,” said Dana Morin, president of Fundy Tidal Inc., which has partnered with ORPC for an upcoming project at Digby Gut in southwestern Nova Scotia.

“In the next 12 months they will have the quantitative, verifiable information that will allow investors to make decisions. There are very few others who have come that far.”

Competitors are fast on their heels, however.

Marine Current Turbines plans to test one of its pylon-mounted devices at the Minas test site, where it has leased one of the four available berths. French engineering giant Alstom and a three-company partnership that includes Lockheed Martin have the other berths, all of which will next month be connected to the province’s power grid by undersea cables.

“We have a big resource right next to the grid, in a province with a friendly regulatory climate that wants to incentivize the industry,” said Matthew Lumley, spokesperson for the test site, the Fundy Ocean Research Centre for Energy. “That’s very compelling.”

ORPC’s primary U.S. rival is Verdant Power, which operated six windmill-like turbines in the East River between Manhattan and Brooklyn from 2006 to 2008 and will begin deploying its first commercial array there in the second half of 2013. “We’re very interested in tidal power in the Maritimes and have our eyes set on several sites,” said Trey Taylor, president of Verdant’s Ontario-based Canadian subsidiary.

Much of the industry’s near-term expansion is expected to be in Nova Scotia, and not only because it has unmatched tidal resources. The provincial government is extremely supportive, having built the Minas test site (for large devices) and provided a premium, guaranteed tariff for electricity fed into the grid from small tidal turbines (rated, like ORPC’s, at less than 500-kilowatts) that are community-owned. (New Brunswick’s government, by contrast, has largely ignored the sector).

“Nova Scotia wants to be a global leader in the marine energy industry,” said Elisa Obermann, regional director of the Ocean Renewable Energy Group, an industry association based in Halifax. “They have the resource and they see it as a significant economic opportunity.”

“The Bay of Fundy as a resource is one of the best in the world, and that’s why the world is beating a path to Nova Scotia’s door to be a part of the development there,” said John Ferland, ORPC’s vice president for project development. “We have a wonderful opportunity to be a first mover and to leverage the success of what we are doing in Maine.”

ORPC’s experience in Eastport may have given it an additional edge in partnering with small coastal communities elsewhere in the region. Although founded by people very much “from away,” the company has become a genuine part of this tight-knit community, having forged successful partnerships with contractors, fishermen, conservationists and local officials.

“Some people know how to be local wherever they are, and Chris Sauer is definitely one of those guys,” said Will Hopkins, executive director of the Cobscook Bay Resource Center, which helped set up meetings early on between the company and fishermen.

“He said, ‘We have this concept and we think it will work, but we don’t know about Cobscook currents and ledges and anchoring systems, from which you’ve all made your livelihoods for decades and centuries.’ He basically invited people to participate in ORPC’s success, and its success has become the community’s success.”

The company’s supply chain extends to 13 of Maine 16 counties, and it estimates it has spent more than $14 million statewide and close to $4 million in Eastport, population 1,600. Once all the turbines are installed in the area, local spending would easily exceed $20 million.

“We have five full-time employees in Eastport right now, and that’s like having 1,000 jobs in Boston,” said Sauer. “Vessel services, diving rigs, certified marine mammal observers — we’ve tapped on a whole pool of local expertise.”

Many of the Nova Scotian communities that are looking to tidal power have striking similarities to Eastport. Down East Maine and southwestern Nova Scotia were colonized by the same European settlement wave before the American Revolution. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, when most everyone worked and traveled in boats, there was regular interaction across the bay.

“I think the boys set out to find women on the other side and vice versa. Fishing and sailing traditions brought the communities together,” said Fundy Power’s Morin, who lives on Brier Island, a community of 300 that he said is not unlike Eastport in its appearance and economic challenges, and is looking to tidal power to help spur development. “On both sides of the channel, fishing is alive but waning, the population is aging, and it’s becoming more of a tourism economy.

“Visually they’re much the same, beautiful and slow in the winter,” he said, “but they share the same currents.”

Staff Writer Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story