In Ghana, where people are so poor they only earn about $1 a day, batteries are in high demand.

In villages with no electricity, they’re needed to power flashlights for security, hunting and doing homework after dinner. They make radios run, giving Ghanians a lifeline to their only electronic source of news. And they power cell phones, which are cheap in Ghana but lose their charge quickly.

Whit Alexander, the inventor of the board game Cranium and a fan of creative capitalism, came up with a business plan to sell rechargeable batteries to people in Ghana so they wouldn’t have to throw away their hard-earned money on regular batteries that quickly die.

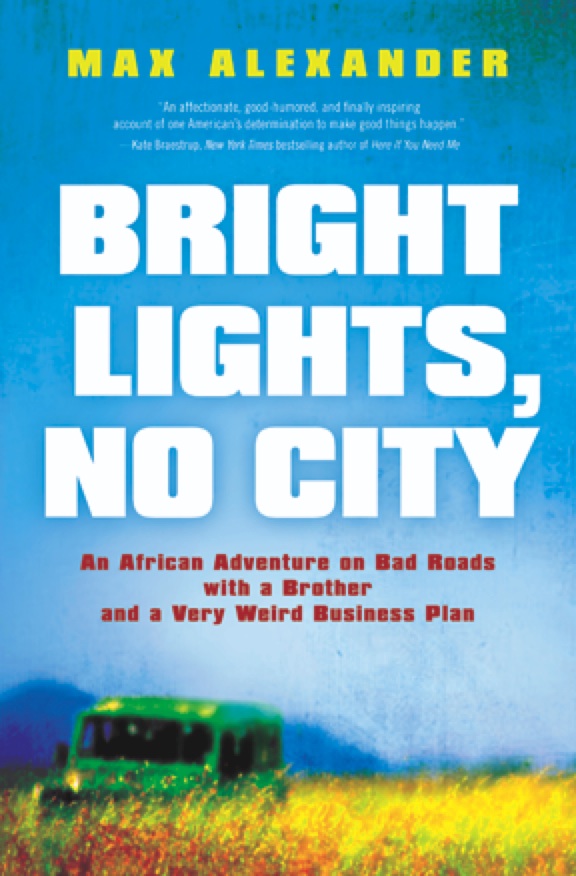

His brother, Max Alexander, decided to travel with him to Ghana and document all the crazy cultural bumps in the road he faced as he tried to launch Burro, the new battery business. The result is “Bright Lights, No City: An African Adventure on Bad Roads with a Brother and a Very Weird Business Plan” (Hyperion, $24.99).

Max Alexander, 55, is a former executive editor of Variety and Daily Variety, and a former senior editor at People magazine. He moved to Maine about 10 years ago, documenting his family’s transition from New York in “Man Bites Log: The Unlikely Adventures of a City Guy in the Woods” (CreateSpace, $15 in paperback).

The Alexanders have sold the Maine farmhouse in Washington that they initially called home and now live in South Thomaston, in an old house where they raise chickens. Alexander and his wife, Sarah Baldwin, are the parents of two boys. Harper will be a college junior this fall, and William is a junior in high school.

Alexander chatted with the Maine Sunday Telegram about his experiences in Ghana and how they changed him.

Q: What did you think about your brother’s idea when you first heard about it?

A: I honestly was sure he was going to fail. My brother founded Cranium in the ’90s, the board game. And when he started that, I was pretty sure that was going to fail too, just because he’s my kid brother and I kind of have a hard time picturing him being a real entrepreneur. So I looked at Cranium and I said, “There’s too much stuff going on in the game, and kids are going to choke on the pieces.” I just felt sorry for him. I thought “Oh man, hope I can find the words to talk him off the window ledge when this fails.”

It turned out that I was wrong, fortunately. But then after he sold Cranium to Hasbro, he had this idea to go back to Africa, where he had lived as a younger man, and start a new business basically trying to sell products to people who live on a dollar a day in a country with a fairly long history of coup d’etats followed by firing squads. And I looked at that and I thought, as business plans go, this seems very similar to New Coke or Edsel. Fortunately, it ended up being a really great adventure.

Q: Why did you decide to join your brother in this project?

A: Well, I went over there first to get a look at it, thinking there could be a book there. And what really appealed to me was I saw how my brother was interacting with these really poor developing world citizens in a way that wasn’t pitying them as victims or treating them like hopeless charity cases. He was just going in there to these villages and saying, “Look, I have these really cool products and they’re going to work better than what you’re buying now, and they’re going to help you do more on your farm. Yeah, they’re going to cost a little more, but they’re going to work well, and I’m going to back them up with guarantees,” which they’d never heard of there.

Q: What were some of the biggest challenges that you faced? Were they more cultural challenges or business challenges?

A: In a way, both were rolled into one, because many of the business challenges were cultural. For example, like hiring employees. The nature of my brother’s business is that he would have to deliver these batteries to all these remote villages, so he required employees to drive cars. Most Ghanaians don’t know how to drive. My brother basically, in order to make his business work, had to teach these adult Ghanaians how to drive. The driving over there is pretty insane. Ghanaians, I like to call them theological drivers. They pretty much believe everything’s in the hands of God, so why not pass that truck on a blind curve? What’s going to happen is going to happen. It’s fatalistic, you know.

Q: Do you think this sort of business model could work in poorer communities in the United States?

A: Yeah, that’s a good question. I do, I do. And I’m not exactly sure now that I’ve said that how it would work. But I think the principle of dignifying people as intelligent consumers and giving them a choice of good products that work really well and that help them in their lives, I think there could be more of that in poor communities in the West too.

One of the main ways Westerners are making money in the developing world is by selling them sugar water and alcohol and cigarettes. OK, I get it, people want that stuff, and it’s filling a need. But it’s nothing my brother would ever do. I think there could be a lot of opportunities, even in poor communities in the U.S. — I’m thinking in particular maybe on Indian reservations — to bring products and goods and services that aren’t harming peoples’ health, that’s actually making them live better lives.

There’s always a need for charity, especially when it comes to the big problems in the world — eradicating polio, finding a cure for malaria, bringing electrical power on the grid to these places. All of these big intractable problems are not going to be solved by little entrepreneurs like my brother, or really anybody in business. That takes a concerted effort of government and nonprofit groups, and that’s always going to be the case. Disaster relief, another example.

But beyond those things, I think when you’re on the ground, giving stuff away for free brings a lot of problems with it. Giving stuff away creates shortages, it creates rationing, it creates corruption. And there’s no contract when you do that. So you give somebody a flashlight and it breaks in a week. “Hey sorry, I gave it to you. I’m sorry it broke, but it was free, so what do you want?” It’s like you kind of wash your hands of the whole situation. Then it also leads to this problem where free is everyone’s favorite price, so yeah, people are going to take something that’s free. But that doesn’t prove they want it. If you want proof they want something, you’ve got to see what they’ll spend their very hard-earned money on.

Q: You said in the book you wanted to know what it was like to be in a place without a consumer culture. How did this experience change your perception of the United States, which is kind of the ultimate consumer culture?

A: It’s pretty interesting. The Ghanaians, one thing that really struck me is those people are filled with so much joy, and they have nothing by our material standards. They just have nothing, and they’re still so happy.

Don’t get me wrong; they would love to have our stuff. They “get it.” They know what stuff is. They’ve seen television. They listen to the radio. They’ve got billboards. They know what computers are. They’d love to have that kind of stuff, but they don’t and they can’t, at least not right now, and they’re OK with that.

People are working hard and trying to make their lives better, but they don’t get all hung up about it. They measure their wealth, if you will, and their success by their family ties, by their friendships, and perhaps most importantly in a country with a staggering amount of illness and disease, by their health. If you’re healthy over there, and your family is healthy, you have a lot to be thankful for. A couple of times while we were over there, children that we knew pretty well died, and in some cases, they don’t even know why.

A corollary is, the conservation of resources is just incredible over there. On basically every block in any town or city that’s larger than a little village, there are shops where guys are in there with magnifying glasses and soldering irons, taking apart radios, televisions, speakers, and fixing them.

There are cell phone stores on every corner, where if your cell phone breaks, you can take it in there and for about $2, they’ll tear your whole phone apart as if it were China and fix it. Here in America, my cell broke and I took it into the dealer in Rockland, and it was like, “OK, well, we have to send this back to China, and it will cost $50 to fix.”

My brother and I grew up in Michigan. Our family goes back making cars for generations. Our grandfather worked on the Chrysler assembly line for 40 years, so we’ve got this sort of manufacturing thing in our Michigan blood. It’s sad in a way when you come back to America and you see that we’ve lost so much of that. We don’t make stuff nearly as much as we used to, and the average person doesn’t really know how to fix something anymore. They just throw it away.

Q: Are you working on anything new?

A: I’m working on a book idea I want to do in China, kind of a subversive travelogue. I’ve been spending a lot of time in China, and I’m just fascinated by the country as being kind of a strange cross of totalitarianism and capitalism, and how all that works. My interest in China was sparked by my current book, because my brother and I went over to China to find products for his business in Ghana.

I’ve been studying Mandarin with a teacher up here on the Midcoast, which is a joke, but I’m enjoying it. I don’t think I’m ever going to be fluent in Mandarin, but I’m definitely enjoying the experience of trying to learn a completely, totally foreign language at the age of 55. So that’s what I’m working on now.

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.