Like many early newspapers, the Portland Daily Press, forerunner of the Portland Press Herald, was borne of political kindling at a time of great turmoil in our state and our nation.

The year was 1862. Slavery and the Civil War were tearing the United States apart and creating fevered demand for daily news. Abraham Lincoln was president and Hannibal Hamlin, a prominent Maine politician, was vice president.

They were the first Republicans elected to our nation’s highest offices, winning hearty support from Maine’s fledgling Republican Party for their efforts to preserve the union and end slavery.

But neither of Portland’s major daily newspapers supported Lincoln or his party, at a time when most papers delivered news with a distinct political tone, making no attempt to offer a balanced view.

The Portland Daily Advertiser, formerly headed by Republican newspaperman and future Gov. James Blaine, had switched party lines, according to Joseph Griffin’s “History of the Press of Maine,” published in 1872. The Advertiser was trying, unsuccessfully, to challenge the Daily Eastern Argus for Democratic readers, who were divided on the slavery issue.

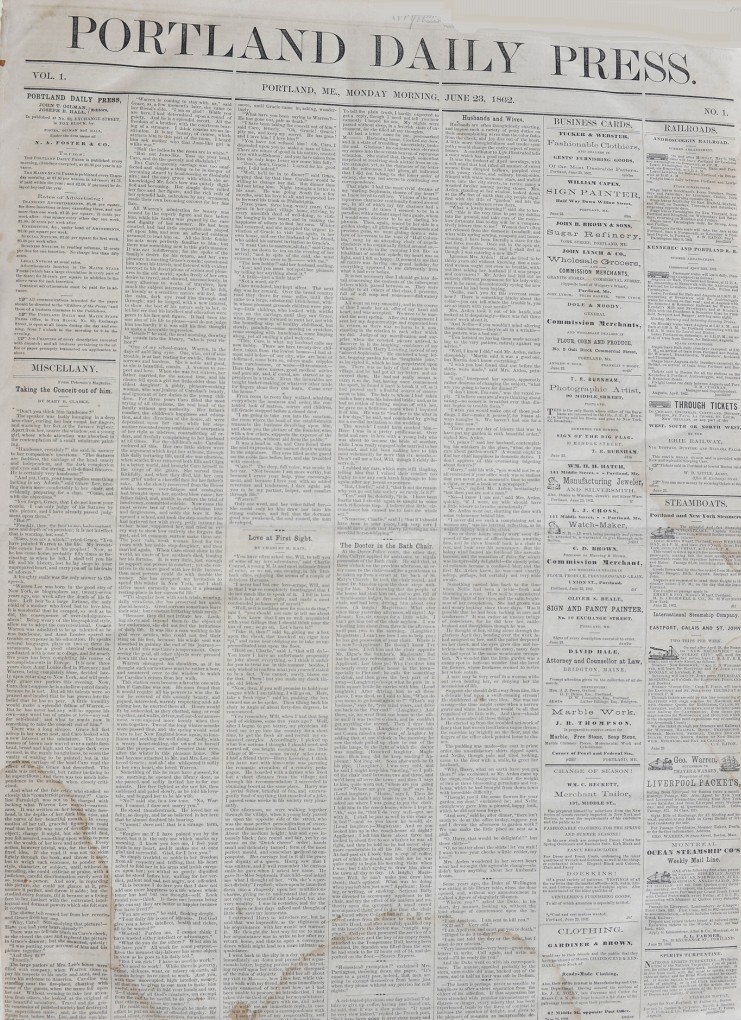

The Portland Daily Press, launched by Newall Foster, John Gilman and Joseph Hall, was crystal clear on the slavery question.

The first edition, published June 23, included a lengthy prospectus that promised the paper would oppose slavery “as the foulest blot upon our national character.” It would back Lincoln in the “peaceful removal of our greatest moral, political and social evil.”

Signed by Republican state, county and city committee leaders, the prospectus pledged that “the Press will give earnest, cordial and generous support to the administration of Abraham Lincoln, who in little more than one year, has indelibly impressed himself upon the nation’s heart as an incorruptible patriot, an inflexible chief magistrate and an honest man.”

Within a year, the four-page Portland Daily Press claimed the highest circulation in the city, in a state where the Republican Party would dominate into the 1950s.

The Daily Press was one of 38 daily, weekly or monthly newspapers published in Portland between 1870 and 1890, wrote the late Alan Miller, a longtime University of Maine journalism professor, in his 1978 history of Maine newspapers. But most of them were short-lived, and only five dailies survived at the end of the 19th century.

Party politics defined editorial and news-gathering policies at the Daily Press well into the 1900s, as was the case at nearly all American newspapers dating back to the Colonial era, said Ken Paulson, president of the First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University. Newspapers in the 1800s in particular were plentiful, distinctly partisan and not very lucrative.

“You did not start a newspaper to make a buck. You started a newspaper to make a point,” said Paulson, former senior vice president of news at USA Today. “Having a niche gave you a built-in audience.”

As recently as the 1960s, Paulson said, most major dailies were known to have political coverage and readers with a certain point of view. As the number of newspapers declined, often leaving one major daily or one newspaper publisher in many cities, owners increasingly were forced to provide balanced coverage to stay in business.

“It was a happy intersection where good journalism equaled good business,” Paulson said.

The Daily Press was “way ahead of the curve,” Paulson said, when Guy Gannett bought the paper in 1921 and decided to provide the first balanced coverage of political campaigns in Maine.

That same year, Gannett also bought the Portland Herald, another morning daily that was started in 1920 by a group of local merchants who were upset about the high cost of advertising in the popular Portland Evening Express.

The merchants had taken over the struggling Daily Eastern Argus, a Democratic daily that began in 1803. They shut down the Argus on Jan. 26, 1920, and started publishing the Portland Herald the next day.

A year later, neither the Daily Press nor the Portland Herald was doing well. While most merchants bought ads in the Herald, which hurt the Daily Press, neither morning paper could compete with the Express, the city’s only evening paper.

“The new paper claimed a circulation of 8,000, compared with 12,000 for the Press and more than 24,000 for the Express,” former Press reporter Harold Boyle wrote in a 1980 column about what he called the “big strangle.”

Running out of options, the owners of each morning paper asked Gannett to buy them out. He was a prominent Augusta businessman, Republican party leader and publisher of Comfort, a popular national monthly magazine.

Gannett was reluctant to buy either paper, so U.S. Sen. Frederick Hale of Maine, a Republican who owned the Daily Press, invited Gannett to Washington, D.C., where he met President Warren Harding, a Republican who owned the Marion Morning Star in Ohio.

“(Harding) told Gannett that newspapers were a sound investment,” Miller wrote in “The History of Current Maine Newspapers.”

Gannett eventually agreed to buy the Daily Press and the Portland Herald, and he consolidated them into the Portland Press Herald, first published on Nov. 21, 1921. The deal included the Portland Sunday Press, which became the Sunday Press Herald.

Gannett riled his Republican colleagues during the Press Herald’s first year, when circulation exploded from 18,070 to 28,905 and the paper cost 2 cents a copy.

As a member of the Republican National Committee, Gannett shocked party leaders during the 1922 gubernatorial campaign, when he published criticisms leveled by Democratic candidate William Pattangall against Republican incumbent Gov. Percival Baxter.

Gannett responded with an open letter to readers explaining his desire to cover political news fairly and keep it separate from opinions expressed on the editorial pages.

“The American people think for themselves,” Gannett wrote. “They want and should be given the news and all the news fully and uncolored by any personal or political consideration.”

Gannett made his case again in 1924, amid Republican President Calvin Coolidge’s successful re-election bid. A publisher’s note explained that readers had come to expect and appreciate reading exactly what candidates said during campaigns.

“We suppose there are still a few Republicans in Maine who prefer a newspaper to print only the good things that are being said about their party or their candidate,” the column said. “If so, they have plenty of newspapers in Maine which they can read and not be offended.”

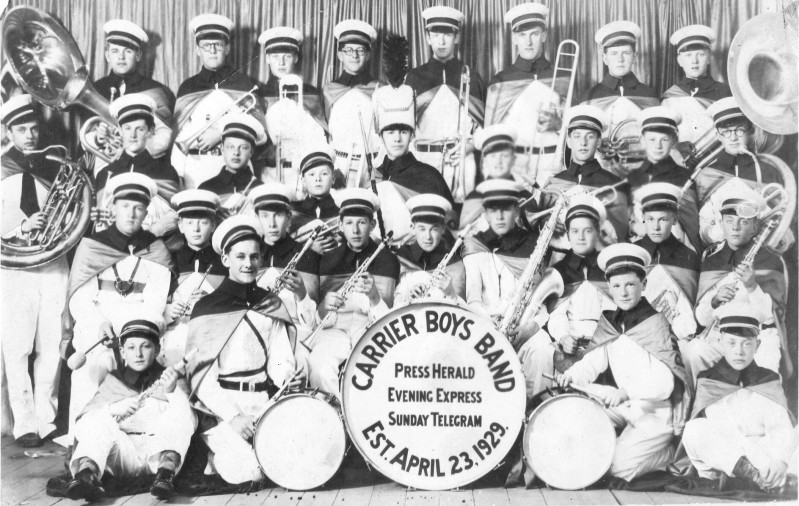

In 1925, Gannett bought the Portland Evening Express and Daily Advertiser, which had evolved from the state’s first newspaper, the Falmouth Gazette & Weekly Advertiser, started in 1785.

Gannett shortened the name to Evening Express. His deal with former owner Frederick Neal Dow, another prominent Republican, included the Portland Sunday Telegram, which became Gannett’s only Sunday paper.

By 1929, Gannett’s company also owned the daily Kennebec Journal in Augusta and the Central Maine Morning Sentinel in Waterville. Gannett expected balanced political coverage from each of them.

Despite Gannett’s early promise of fairness, the Portland Press Herald continued to field criticism on the subject. The issue was addressed by at least two independent studies.

In 1959, Brooks Hamilton, a University of Maine journalism professor, studied both the Portland Press Herald and the Bangor Daily News for evidence of bias in stories about recent campaigns. Both Democrats and Republicans had charged that the papers deliberately printed biased stories or displayed them in ways that would influence the elections.

“All in all, our study does not show evidence to support the charges as made,” Hamilton reported. “It should not be necessary here to labor the point that there is much news that does not please candidates or publishers, but which must be published if reader interests are to be served.”

A 1974 study sponsored by the New England Newspaper Association found that the Press Herald managed to “shun special interests and be all things to all people” and offered a “spirit of comprehensiveness that probably is matched by few other papers (its) size.”

Through the years, the Press Herald has covered and endorsed candidates of various political persuasions, including independents Angus King, who was elected governor in 1994 and 1998, and Eliot Cutler, who came in second in the 2010 gubernatorial campaign.

In 1950, the Press Herald won praise from controversial, far-right Republican U.S. Sen. Owen Brewster of Maine. The Portland lawyer had been sympathetic to the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, opposed FDR’s New Deal policies in the 1930s, accused Howard Hughes of wasting millions in federal funding in the 1940s and was a friend of Communist-hunting Sen. Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s.

On Aug. 31, 1950, Brewster “complimented the Press Herald on the Senate floor and placed in the Congressional Record three articles,” including a story about Republican attitudes on the Korean War written by May Craig, Washington correspondent for the Gannett newspapers.

On the paper’s 100th anniversary in 1962, President Kennedy, a Democrat, sent a letter congratulating the Press Herald for playing “a vitally important role in our society” by providing effective news reporting.

“(Newspapers) have the obligation to report local, national and international news fully and accurately,” Kennedy wrote. “They also have the equally great obligation of contributing to our national strength and vitality. The Portland Press Herald has fulfilled this responsibility well.”

In 2008, when the Portland Press Herald and Maine Sunday Telegram were owned by the Seattle Times Co., the papers endorsed Democrat Barack Obama over Republican John McCain.

Today, the newspapers’ majority owner is S. Donald Sussman, a weatlhy financier who lives in North Haven and is married to Democratic U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree. Sussman has promised to leave editorial and news-gathering decisions to the papers’ independent staff members, said Executive Editor Cliff Schechtman.

“He told me to put out a great paper and tell people what they need to know,” Schechtman said. “We’re going to build on our great heritage and produce probing, public-service journalism without fear or favor.”

Schechtman said he believes in keeping a firewall between news and editorial pages.

“I view the opinion pages as a place to conduct a community conversation about current issues, where all voices are welcome,” Schechtman said. “The editorial staff takes positions that reflect what’s best for Maine and the people who live and work here.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story