We have this idea in America that important paintings should be big. Really big.

While this is a holdover from Abstract Expressionism, the idea goes much deeper into 19th-century Paris-led culture of giant narrative tableaux.

Yet it can be argued that Modernism painting developed as a response to these absurdly affected giant paintings.

This came to mind when I was visiting “Expanding Fields” at Rose Contemporary in Portland for the third or fourth time. Something about that show intrigued me, and I couldn’t quite put my finger on it.

The show comprises small, nicely framed oils by Jessica Gandolf, pattern-based gouaches on paper by Penelope Jones and acrylic on shaped wood panels by Bridget Spaeth.

It’s a very handsome show. The works are all small and hung with plenty of breathing room. They are even grouped with color design in mind.

What’s interesting is just how many aspects of the work by these three women — all of whom are teaching now at either Bowdoin or Bates college — relate to each other. Most notable are the works’ intimacy and casual relationships to abstraction and spirituality.

In short, these paintings could hardly be more different from the giant Salon tableaux.

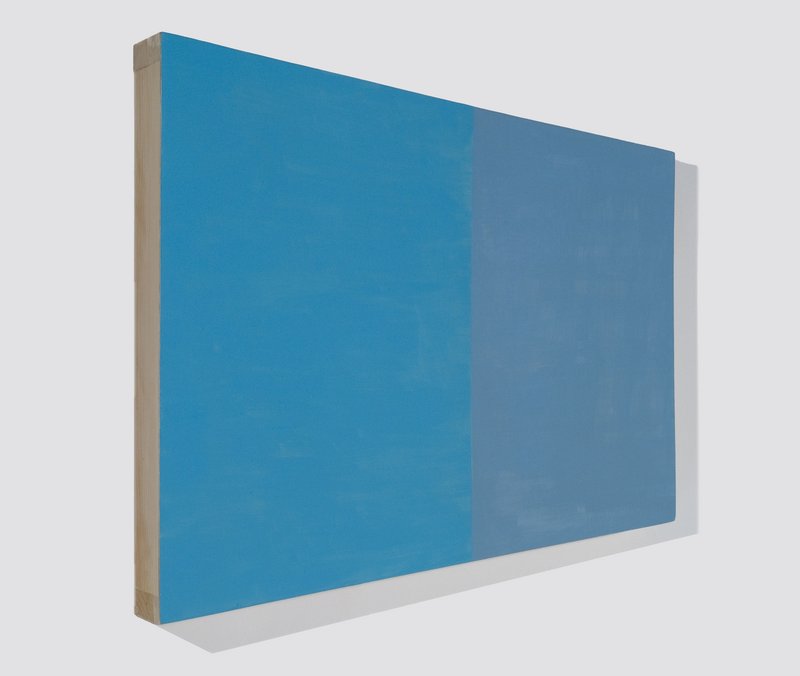

While the spirituality of the work is extremely subtle, it’s fundamental to the experience of all three, and comes in the form of intuition. Spaeth’s, in some ways, is the most obvious. Her “White Subtle Arc,” for example, is a 6-inch-tall horizontal band that flows out 3 inches from the wall and back. It makes a very clear reference to the viewer’s body and visual field, and then some classic mystical abstraction such as Kasimir Malevich’s “White on White” paintings.

Quiet elements such as shadows and reflected light get some play in Spaeth’s elegant work. While this is her most subdued piece because it has the quietest colors, it’s an extraordinary bit of color work.

Spaeth’s other pieces employ heftier colors — pink and orange or, more often, monochrome variations such as her “Blue Trapezoid,” which uses its shape to further an optical illusion. It is this that relates the work to a Baroque mentality. While it is small and relatively quiet, the color, emotive forces and reliance on intuition rather than rationality places this — and the rest of the work in the show — in a spiritualist Baroque mode.

Gandolf’s work is even more intuitive and open-ended. It also has a surprisingly casual relationship to abstraction. Gandolf’s small paintings are tight and beautifully controlled, but it’s clear she doesn’t have a set plan when she begins, and doesn’t seek to limit herself.

This might seem a stretch, but when artists’ work ranges so much from piece to piece, it’s often because they work without a set plan. I like that Gandolf gets varied results; the fact that some pieces are much stronger proves she’s not working from a recipe.

I particularly like Gandolf’s “Morning.” It’s something like a yellow grid of brown forms with shadows. While the colors seem simple at first, there are actually dozens of pigments in the piece quietly hiding in the shadows. Gandolf knows how to handle a brush and finish a piece — that she uses nothing but top shelf paints only plays up her clear respect for the viewer.

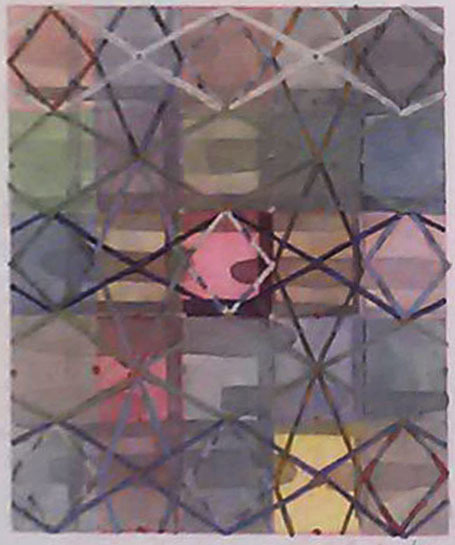

More typical of Gandolf are her “Colony” and her “Aquatic,” in which multiple forms have a rhythmically colorful microscopic logic.

Jones layers her work with rhythmic patterns based on real world systems. Yet by putting multiple systems together, she takes her work away from references and back to abstraction.

While the systems are complex and rigorous — elements such as patterns from a geometrical coloring book, Eastern European tile patterns and even one based on the metal structural scaffolding on her brother-in-law’s antique steam yacht — by placing these together through her own associations, they leave behind any rational narrative.

ANOTHER SHOW that helped me draw my conclusions about “Expanding Fields” is Veronica Cross’ “Cast in Amber” at Elizabeth Moss Galleries in Falmouth.

Cross has a direct line on a sort of everyday mysticism in Maine — fully apparent in her sunsets but no less in her cars junked in fields or, most poignantly, in a green tractor painted and collaged into the center of a spare, snowy landscape. Her collaged pieces sometimes jump off the canvas.

Like the works in “Expanding Fields,” Cross doesn’t try to convince the viewer of her brilliance or profundity when she makes a mystical gesture — in stark contrast to the heroic, profound self-importance of AbEx’s mystical machinations.

Like Jones, Cross also layers disjunctive images intuitively. Her “Double Pilgrim” blends something like a snapshot of an aquaduct reflected in water with mirrored symmetrical reflections of a woman drawn with the brush over the scene. Using an intentionally limited palette, Cross’ image is dreamily confused, emotional and transportive.

While Cross’ images use rhythms so complex they don’t sit particularly well together (I don’t envy whoever had to hang that show), each functions on its own with an impressive personal depth.

I like intimate paintings. I like being drawn in close so that you can see every mark within the image. While I enjoy those giant Salon machines more than anyone else I know, I like where painting is going. This is a pair of very good shows.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story