AUGUSTA – Substance abuse problems among young parents have driven up the number of children in foster homes by 35 percent over projections, prompting state human services officials to seek an extra $4.2 million from the Legislature.

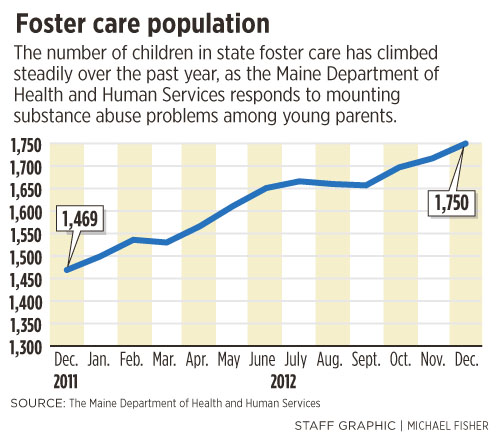

The Department of Health and Human Services says that in 2011, it expected 1,400 children to be in foster care by this June, the last month of this fiscal year.

As of Friday, 1,721 children were in state custody, and the DHHS expects 1,800 to 1,900 to be in foster care in June. That’s more than it can handle with the $36.2 million it budgeted for foster care and adoption subsidies for the year, said Therese Cahill-Low, director of the DHHS’s Office of Child and Family Services.

Cahill-Low attributed the increase to a confluence of issues — mostly prescription drugs, but also economic hardship and the recent phenomenon of “bath salts,” a synthetic drug that is known to cause fits and delusions.

She said caseworkers are seeing children living under unprecedented circumstances, mostly with parents younger than 35, many of them teenagers.

“We’ve seen parents in trees; we’ve seen weapons being displayed when people are on substances more and more than what caseworkers report that they saw in the past,” she said.

Advocates say drug and alcohol abuse have long been a major factor in foster care placement, and they confirmed the trend that Cahill-Low described.

“We seem to be seeing an increase in substance abuse and the types of drugs used,” said Bette Hoxie, executive director of Adoptive and Foster Families of Maine in Old Town, a support, advocacy and education group.

The foster care funding request is one of the few spending initiatives the DHHS is pursuing at a bleak financial time. The department faces a $112 million budget shortfall for this fiscal year, blamed largely on higher-than-expected costs for MaineCare, Maine’s Medicaid program.

Before the Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee on Tuesday, Robert Blanchard, an associate director in the Office of Child and Family Services, said the DHHS started noticing the increase in November 2011, after steady progress in reducing the number of children in foster care from a high of about 3,000 around a decade ago.

Major changes came to Maine’s foster care system after a watershed moment in 2001, when the system was criticized after the death of 5-year-old Logan Marr of Chelsea. Her foster mother, Sally Schofield, was convicted of manslaughter for asphyxiating the girl with duct tape.

Schofield was a caseworker when she took Marr in, and the state later said the DHHS caseworker assigned to the girl didn’t oversee her adequately and had a friendly relationship with Schofield.

The case contributed to the department’s decision to emphasize kinship care — placing children with other family members whenever possible — rather than in foster homes.

From January 2001 to January 2011, the number of children in foster care dropped from 2,956 to 1,461.

From 2006 to 2010, the number of children in state custody placed in kinship care jumped from less than 18 percent to nearly 39 percent, according to the Maine Children’s Alliance, a nonprofit advocacy group for children.

Experts say kinship care is a cheaper, more permanent and nurturing environment for children.

The children’s alliance said the move toward increased kinship care led to an 86 percent savings in the state’s residential costs for children from 2006 to 2010.

Dean Crocker, the state’s child welfare ombudsman, said economic factors are working to put more children into the foster care system.

He points to a 2011 study by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, reporting that about one in five Maine children younger than 5 lived in poverty. At the same time, DHHS data shows that 42 percent of children in foster care, 721 children, are 5 or younger.

“When you put that together with the substance abuse epidemic, I don’t think you have to look much further into it,” Crocker said.

Andi Chasse of Lyman has been a foster parent for 29 years. In that time, she said, she has taken in too many children to count and adopted eight of them, all after they turned 18.

“In my experience, substance abuse or alcoholism was involved in 99 percent of all cases,” she said.

Crocker and state Rep. Richard Farnsworth, D-Portland, the House chair of the Health and Human Services Committee, said ever-tightening state budgets and cuts to child care programs like Head Start may be part of the foster care problem.

But Cahill-Low, the DHHS official, said the demand for foster care started to grow even before the program cuts occurred.

To Farnsworth, the state may need the extra money for foster care because of cuts in other places.

“It’s like a balloon. You can squeeze it, but the air doesn’t go anywhere, it just goes out to the sides and eventually pops,” he said.

“The need isn’t going to go away, it’s just going to find another place to pop up.”

Farnsworth and Rep. Richard Malaby, R-Hancock, another Health and Human Services Committee member, said the Legislature is obligated to support the proposed increase in funding.

“What are we going to do? Put the kids on the street?” Farnsworth asked.

“If it costs us, it costs us. We’re prepared to pay,” Malaby said. “This is the right thing to do. This is our youth.”

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard contributed to this report.

State House Bureau Writer Michael Shepherd can be contacted at 370-7652 or at:

mshepherd@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story