Why do we have such a fascination with old menus?

Maybe we like seeing that we have something in common with our great-grandparents, who apparently loved oysters and macarons as much as modern-day Portlanders.

Or maybe it’s the satisfaction of knowing that, unlike visitors to the Hotel Fiske in Old Orchard Beach in 1890, our servers will never – ever – place before us an entree of “Braised Calf’s Head, brain sauce.”

There’s lots of fun trivia to be found in old menus. How else would we know that Albert Einstein supped on turtle soup and saddle of lamb when he accepted the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921? Or that Henry IV’s coronation feast in 1399 included bitterns, herons, egrets, peacocks cranes, curlews, pigeons, snipe and an assortment of “smal byrdys”?

Old menus also feed our fixation with the idea of “the last meal.” We may never be on death row or go down with a sinking ship, but we can ponder whether we would want our last lunch to include eggs Argenteuil or chicken a la Maryland, as it did for the ill-fated passengers of the Titanic. (That menu, by the way, sold for $120,000 last year.)

Other folks long for the days when a cup of coffee cost a nickel and a sirloin steak dinner was 50 cents.

When I heard that the Maine Historical Society had a collection of old Maine menus, I couldn’t help heading down the street to have a look. The collection includes some historical gems, as well as menus from restaurants that are still around, and some that are gone but not forgotten.

Here’s a look at some of the menus that come with a big helping of nostalgia:

RIVERTON PARK CAFE

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

I’ve always hated that saying, but I have to admit it went running through my mind as I gingerly held a menu that had been printed circa 1900 for Portland’s Riverton Park Cafe.

For those of you who don’t know, the Riverton Trolley Park was a happening place at the turn of the last century. Portlanders paid a nickel to ride the trolley from Monument Square to the park so they could watch vaudeville, take boat rides on the Presumpscot River, play croquet, visit the wildlife zoo and watch acts as varied as Japanese acrobats and a counting horse in the outdoor theater.

The park also had a little cafe. Its bill of fare, along with other turn-of-the-century menus, shows that modern-day Mainers like to eat some of the same dishes their great-grandparents enjoyed.

Think oysters are hot now? At the Riverton Park Cafe, you could order a bowl of oyster stew for 25 cents or indulge in an order of fried or “fancy roast” oysters for 30 cents.

Macaroons (or macarons) are a currently trendy confection that also appear on the park’s menu, although they don’t specify if they mean the colorful sandwich cookies made with almond flour or the coconut cookies. If you lived in Portland in the late 1800s or early 1900s, you could enjoy a 10 cent macaroon after you downed your 50 cent sirloin steak.

The cafe also offered a variety of sodas and tonics, including Simmons & Hammond root beer, birch beer and that old Maine favorite Moxie. Today, old-fashioned craft sodas are making a comeback, and can be found locally at places like Duckfat or Vena’s Fizz House in the Old Port.

Plus ca change …

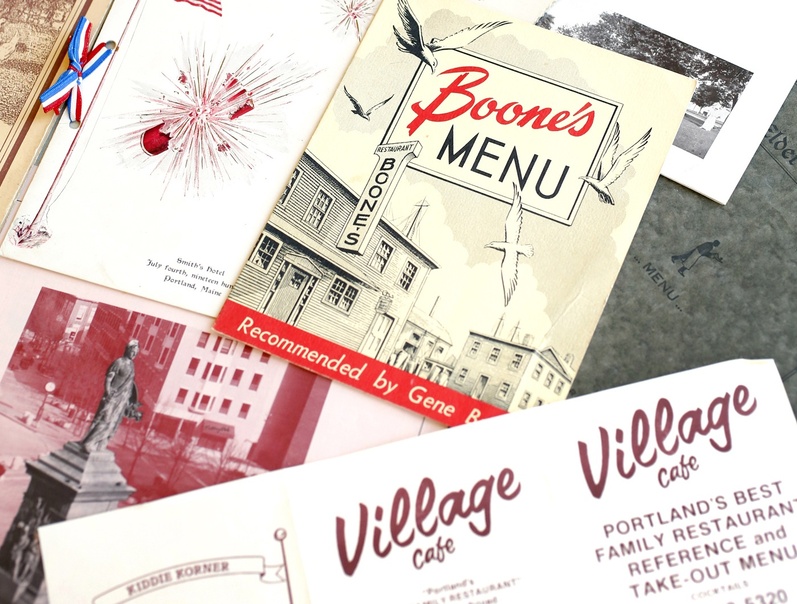

BOONE’S

I was thrilled to find a menu for this historic Portland restaurant because a new place, named after the original Boone’s, recently opened in the same space on Custom House Wharf.

But the joke was on me.

The menu was in pristine condition, but it was a “joke menu.” Funny, occasionally taking a sharp turn into political incorrectness. (One item in particular treads into such sensitive territory, I don’t dare reprint it here.)

For appetizers, the menu lists “Virgin Mermaid on Halfshell” and “Breast of Boiled Peasant, minus de bra.” Entrees include “French Fried French (our fry cook before his foot slipped), large serving 15 cents.”

On the back of the menu is an illustration of cans on a shelf, labeled “Boone’s Delicacies.” They include “Boone’s Skate Fish Lips (Pouted),” “Roast Breast of Lion” and “Boone’s Dehydrated Sebago Water (just add water).”

There are specials, too, such as “Boone’s Boiled Cod Bones Pickled in Brandy. Frankly, this is lousy, but the brandy is delicious.”

EASTLAND HOTEL

This Portland hotel has been in the news lately because it’s undergoing a $50 million renovation.

The new owners are going with a more modern look, but if they wanted to turn to the past for inspiration, all they’d have to do is flip the calendar back to 1939, when the hotel had an Egyptian Dining Room.

There are no photos of the dining room on the Jan. 13, 1939 menu, but there is a description of the space:

“This dining room is believed to be the first, if not the only public dining room of its type in America – the figures represented as being carved in stone after the ancient Egyptian manner. It represents the open air court of Egyptian royalty, in the period of King Pepi II. The mural decorating is in true Egyptian, faithful in detail even to the hieroglyphics, and hieratic numerals of the clock.”

Diners weren’t, however, going to eat like an Egyptian. The restaurant served a table d’hote dinner, a type of prix fixe dinner in which “the price of the entree is the price of the complete meal.”

The entrees included stuffed veal cutlet ($1), banana scallops ($1), lobster thermidor in shell ($1.35) and baked halibut Manhattan ($1). All of the entrees came with an orange and shredded cocoanut (sic) cup, tomato juice cocktail, fish chowder, watermelon pickles, mushroom bouillon, choice of dessert and tea, coffee, milk or buttermilk.

Banana scallops, by the way, don’t really contain scallops. It’s a retro (for us) recipe of coated, fried bananas that were often served like a vegetable.

Tomato juice cocktails and watermelon pickles are two items that pop up repeatedly on the old Maine menus.

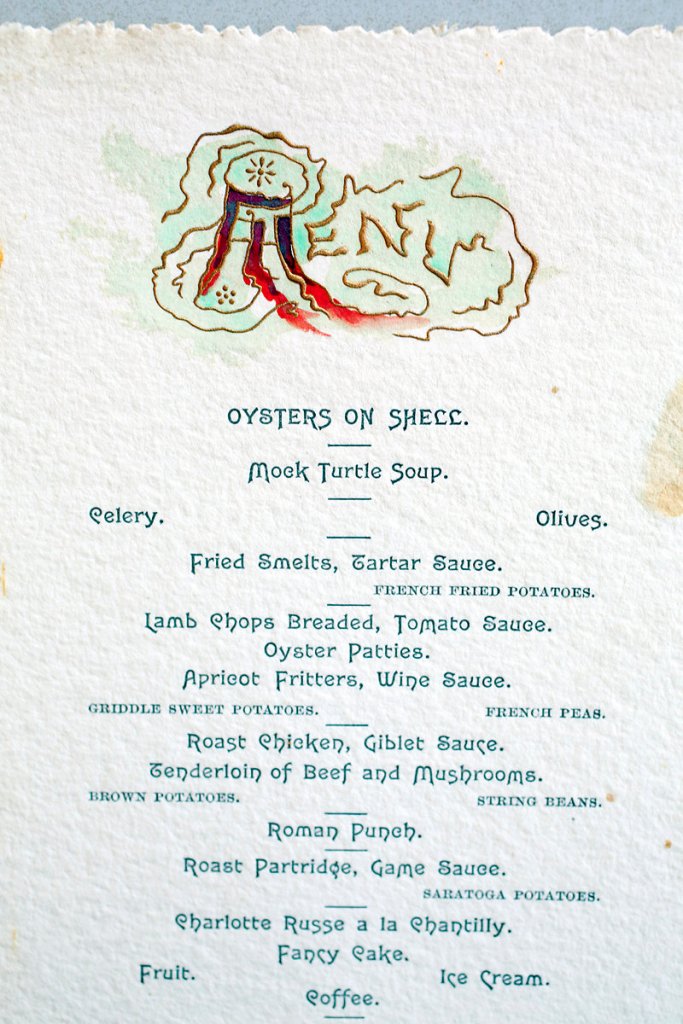

THE PREBLE HOUSE

On Oct. 12, 1888, friends of Alger V. Currier held a dinner in his honor at The Preble House, a grand hotel at the corner of Congress and Preble streets in Portland.

Charles Dickens had stayed at The Preble House in 1868 and found the food “bad and disgusting,” according to a 2012 Maine Sunday Telegram account of his visit. Perhaps the food improved over the next 20 years, just in time for Currier’s dinner.

Currier was an artist from Hallowell who studied painting in Paris. The menu for his 1888 dinner, printed on thick, slightly stained paper, doesn’t mention if the event marked a special occasion, but it was important enough that someone drew a seating chart on the back.

The evening began with mock turtle soup, a dish commonly found on the old menus. Mock turtle soup skipped actual turtle meat, thank goodness, because it was too expensive. The chef used cheaper ingredients (a calf’s head, organ meats, etc.) instead, to impart a similar flavor.

Also on the extensive menu: fried smelts served with tartar sauce and French fried potatoes, breaded lamb chops with tomato sauce, oyster patties, apricot fritters with wine sauce, roast chicken with giblet sauce, tenderloin of beef and mushrooms, Roman punch (commonly used back then as a palate cleanser), roast partridge with game sauce and Saratoga potatoes, and on and on until the meal is finished with coffee and cigars.

The Preble House, by the way, was torn down in 1923 to make room for the city’s popular Time & Temperature building. You can no longer order Charlotte Russe a la Chantilly or Fancy Cake there, but the building will tell you when there’s a snow parking ban so you can avoid getting your car towed.

THE SAMOSET

If you had gone to dinner at the Samoset in Rockport on Sept. 2, 1917, your server would have handed you a menu with photos of men playing golf.

You would have started the evening with a consomme or a crab flake cocktail, which was apparently as popular as mock turtle soup (also on the Samoset menu) at the time.

Entrees included filet of sole a la Meniere, served with iced cucumbers and pommes Parisienne; boiled breast of capon with celery sauce; and stuffed squab with guava jelly.

For dessert, you would have had your choice of blueberry or pumpkin pie, macarons, tutti frutti ice cream, fruits, cheeses, zephyrettes (a type of cracker) or graham wafers.

SMITH’S HOTEL

Someone had such a good time celebrating Independence Day at the Smith Hotel in Portland in 1900 that they saved their patriotic menu decorated with a flag, a drawing of an exploding firecracker, and a red, white and blue ribbon.

This menu illustrates a couple of preferences I noticed over and over again in menus of this time: Strange pairings of relishes, and lots of boiled meats and fish.

The meal started, for example, with a choice of mock turtle soup (again), served with radishes, or mulligatawney soup served with olives. The entrees included choices like leg of lamb and veal cutlets, but there was also boiled halibut with Hollandaise sauce, served with sliced cucumbers, lettuce, potato chips and tomatoes, and boiled ox tongue in piquant sauce, served with pickled beets and pickled onions.

A far cry from our standard Fourth of July hot dogs and hamburgers.

THE GERALD

W.J. Bradbury, proprietor of The Gerald in Brunswick, was so proud of his restaurant that when it opened on June 4, 1900, he put his own photo on the menu.

HOTEL FISKE

This huge hotel in Old Orchard Beach must have had a classier clientele. On the menu for July 20, 1890, the name of the hotel is written in glitter – who knew they had glitter in 1890? – and they served green turtle soup aux quenelles (a type of dumpling) instead of the mock turtle soup made with calf’s head.

They saved the calf’s head to braise and serve with “brain sauce.”

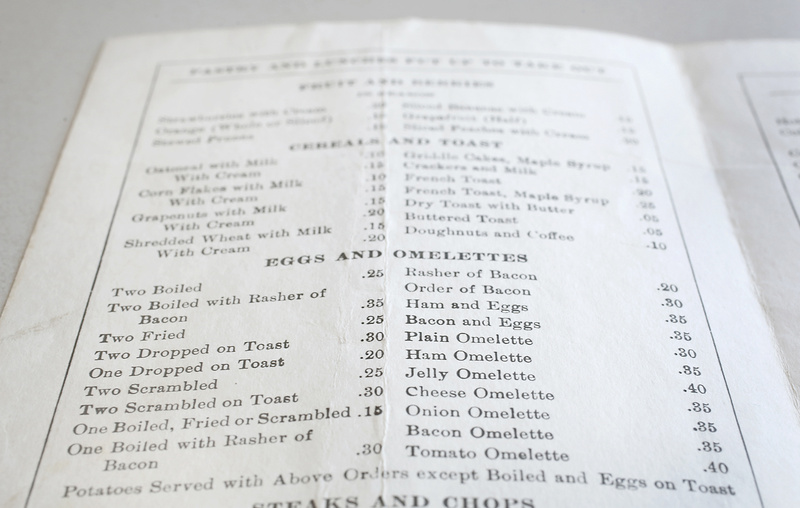

ELDER’S LUNCH

This lunch spot at 71 Oak St. in Portland was owned by an F.L. Elder; the cover of its menu featured a drawing of a waiter holding a tray.

There’s no date on the menu, but the prices leave no doubt that it dates to the first part of the 20th century. Two pork chops could be had for 45 cents, and a slice of pie was a dime.

Customers could eat in or order take-out, and didn’t have to worry about bad service if they followed these instructions printed at the bottom of the menu: “Kindly report any discourteous treatment on the part of employees to management.”

WORSTER HOUSE

This Hallowell hotel and restaurant caught my eye because of its interesting history.

The 70-room structure, originally known as Hallowell House, was built in 1832 to house legislators, and hosted the likes of Cornelius Vanderbilt, Daniel Webster and Ralph Waldo Emerson. In 1841, according to the Maine Historical Society, it became a “temperance house.” The proprietors posted a notice in the local paper that said its “incomparable meals” would “more than compensate for the absence of liquors.”

Yeah, right. Apparently the Worsters never heard that restaurants make much of their profit from beer, wine and liquor sales. They eventually had to close down.

The hotel re-opened, but then closed for good in 1959 so it could be turned into apartments. Today, it is the home of the Public Utilities Commission.

The menu on file at the historical society is dated Sept. 7, 1949 and is stamped “Where Maine Goes to Dinner.” The menu is not all that different from what a restaurant might serve today, except, of course, for the prices. A “broiled fresh swordfish steak” served with drawn butter, for example, was just $1.65, and a plate of fried scallops was $1.50. Sides included “cream whipped potatoes,” whole kernel corn and “cream green peas.”

On the bottom of the menu, management warned: “Minimum guest check $2.”

Finally, this menu was the only one with a poem. It read, in part:

“Guest, you are welcome here, be at your ease

Go to bed when you’re ready, get up when you please.

Happy to share with you, such as we’ve got.

The leak in the roof, the soup in the pot.”

GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

If you’ve lived in Portland for 20 or 30 years, there are lots of old names in the collection to make you salivate and reminisce.

Remember The Roma Cafe, known for ages as “Portland’s most romantic restaurant” and the place you had to take your date on Valentine’s, or else suffer the consequences?

There are also menus for Hu Shang on Exchange Street and the Victory Deli in Monument Square (where Foley’s Bakery is now), both former frequent lunch spots for Press Herald reporters. At the end of the day, when we wanted a cocktail, we went down to Cotton Street Cantina. (On the menu, it’s called Cotton Street Tropical Grill and Bar.)

Our bosses went to F. Parker Reidy’s, the steak house where Sonny’s is now located, for the $2.95 French onion soup, $4.50 broiled chopped sirloin with mushroom sauce, and teriyaki sirloin tips with rice pilaf for $6.50. (The 1980s called) Reidy’s is also where I had my job interview with two top editors, and I still remember that I ordered fish. Hmm, fish in a steak house, and I still got the job.

Fans still maintain a “bring it back” Facebook page for the Village Cafe on India and Fore, where you could get a big plate of spaghetti and meatballs for $3.75.

A couple of the menus made me gasp a little. The first one was from a place I still think about occasionally, Raffles Cafe & Bookstore, which was located at 555 Congress St.

Sound familiar? That’s because that space is now home to Five Fifty-Five.

Now, I admire what Steve and Michelle Corry have done with their restaurants in this city, but who didn’t love going to Raffles for a 75-cent croissant and $1.25 cappuccino on a lazy Saturday afternoon, followed by some book browsing?

Another surprise in the collection was a stunning, colorful Back Bay Grill menu from Autumn 1997. The Back Bay Grill is, of course, still around, but I mention this menu because it hints of things to come in the Portland food scene, including the craft breweries and the love affair with farm-to-table cuisine. The menu’s selection of “regional microbrews” featured only Allagash White, Shipyard’s Old Thumper and Seadog Brewing Co.’s Hazelnut Porter.

I don’t think I ever tried Raphael’s, the northern Italian restaurant that once occupied the space where Market Street Eats is now, but it sure is fun looking at the pink menu. Staring back at you is the restaurant’s namesake, Raphael “Little Willie” Cianchette, the grandfather of Portland businessman Eric Cianchette.

The restaurant had valet parking, piano entertainment in Little Willie’s Lounge and a raw bar. The dish I would most like to try, if I had a time machine: Spinach and egg fettuccine tossed with scallops and shrimp in a Parmigiano cream sauce.

Dinner for two with wine at Raphael’s, according to a 1987 Maine Sunday Telegram review, cost $80.

Who can forget the huge selection of sandwiches at Carbur’s (“Famous since 1977”), all with ridiculous names? There was the turkey and Swiss called the “Jerry Fjord,” the “Maine Maul,” the “Stay Tuna’d” and a hot pastrami called the “Falmouth Foulmouth.”

The Maine Historical Society is considering mounting an exhibit of the menus sometime in the near future, perhaps during Maine Restaurant Week, so you may soon have the chance to check them out yourself.

Stay Tuna’d.

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story