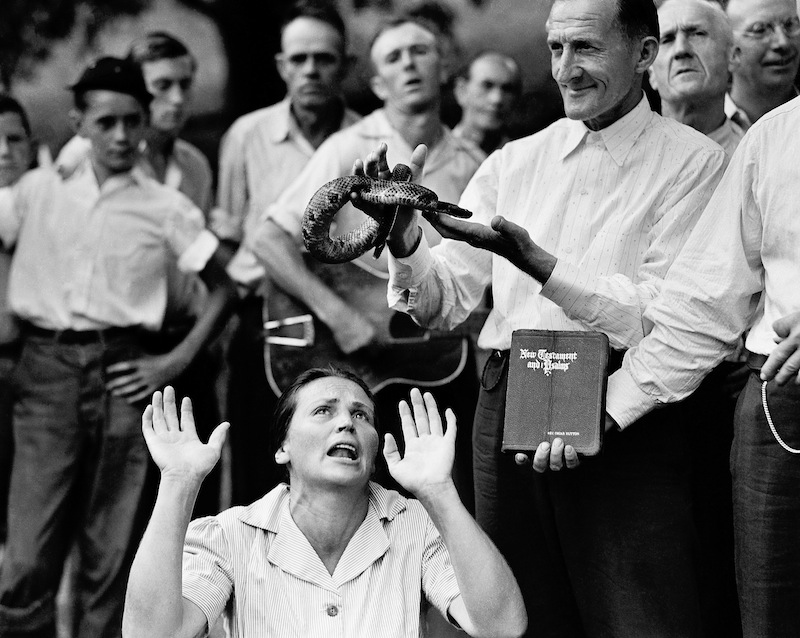

Three days after pastor Jamie Coots died from a rattlesnake bite at church, mourners leaving the funeral went to the church to handle snakes.

Coots, who appeared on the National Geographic Channel’s “Snake Salvation,” pastored the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus Name church founded by his grandfather in Middlesboro, Ky. The third-generation snake handler was bitten during a service on Feb. 15 and died later at his home after refusing medical help. Now his adult son, Cody Coots, is taking over the family church where snakes are frequently part of services.

“People think they will stop handling snakes because someone got bit, but it’s just the opposite,” said Ralph Hood, a professor of psychology at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, who has been studying snake handlers for decades. “It reaffirms their faith.”

The practice of snake handling in the United States was first documented in the mountains of East Tennessee in the early 20th Century, according to Paul Williamson, a professor of psychology at Henderson State University who, along with Hood, co-wrote a book about snake handlers called, “Them That Believe.” In the 1940s and 1950s, many states made snake-handling illegal (it’s currently illegal in Kentucky), but the practice has continued, and often law enforcement simply looks the other way.

The basis for the practice is a passage in the Gospel of Mark. In the King James Version of the Bible, Mark 16:17-18 reads: “And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.”

Snake handling gained momentum when George Hensley, a Pentecostal minister working in various Southern states in the early 1900s, recounted an experience where, while on a mountain, a serpent slithered beside him. Hensley purported to be able to handle the snake with impunity, and when he came down the mountain he proclaimed the truth of following all five of the signs in Mark. Hensley himself later died from a snake bite.

Today the practice is most common in Southern Appalachian states, and snake handlers often use native rattlesnakes and copperheads. Such churches are independent, and often call themselves “signs following” churches.

Andrew Hamblin, who co-starred on “Snake Salvation,” said he was with Coots when he died.

“I held him in my arms when he took his last breath,” said Hamblin, who is pastor at the Tabernacle Church of God in the nearby community of LaFollette, Tenn.

He believes that Coots, 42, would have died Feb. 15 no matter what; If not by a snake, then a stroke or some sort of accident.

“God’s appointed time of death trumps everything,” Hamblin said.

Williamson said believers describe the feeling they get when they are handling snake, “Like a high, but a greater high than any drug or alcohol. It’s a feeling of joy, peace, extreme happiness.”

He said that many snake handlers believe that when God anoints them, they will be protected, but they still recognize there is danger. For instance, if the spirit leaves them and they don’t put down the snake quickly enough, they could be bitten.

Coots had handled snakes many years and had been bitten several times, always relying on prayer, and not medical help, to heal him. In “The Serpent Handlers: Three Families and Their Faith,” a book focusing on prominent snake-handling families, Coots is interviewed and describes a bite that took part of his finger, saying he had done something he shouldn’t have done (he doesn’t say what) and God was punishing him. Describing another painful bite, Coots says he was bitten after the spirit had moved out of him but he continued holding the snake for egotistical reasons.

Hood knew Coots well, and attended his standing-room only funeral service last week. At a gathering at the church afterward, some mourners were handling snakes, he said.

“At the service, what everybody recognized and accepted is that he died obedient to God and that his salvation is assured,” said Hood.

At church service on Saturday, a week after Coots died, both Cody Coots and his mother handled the rattler that killed his father, said Williamson, who attended the service. Calls to the Coots family have not been returned.

Williamson said he has documented 91 snake bite deaths among serpent handlers since 1919; Between 350 and 400 people die from snake bites in the U.S. each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Williamson said questions of why a snake-handling believer dies from a bite are no different from the questions believers of various faiths have about why bad things happen to good people.

Coots’ death was the second snake bite death at his church, which was founded in 1978. Melinda Brown, a 28-year-old mother of five, died in 1995, two days after she was bitten by a rattlesnake during a service.

Coots was then a 23-year-old pastor, and Brown spent the two days it took her to die at Coots’ house. At the time, Coots told reporters that Brown had decided to put her fate in God’s hands rather than go to the hospital.

“Everything that happened, where it happened, was the Lord’s will,” Coots said.

Brown’s husband, John Wayne “Punkin” Brown, continued to handle serpents after his wife’s death. He was killed by a snake in 1998, at the age of 34, while preaching at an Alabama church.

His last words to the congregation were, “No matter what else, God’s still God.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story