Carol Donnelly thinks of the York River as the middle child of rivers in Maine.

“It’s not in dire straits and it’s not the biggest, the longest or the most important river in the state,” she said. “It’s sort of the forgotten piece, but it is a gem.”

Donnelly and a group of other York residents have taken their efforts to study and protect the low-profile, 11-mile-long river all the way to Congress.

The House of Representatives unanimously passed a bill last week to pay for a multiyear study and determine whether the river is eligible for designation by the National Park Service as a Wild and Scenic Partnership River. A similar bill is working its way through the Senate, which has referred it to the Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

If the bill is approved, as much as $300,000 will be available for the study, which takes about three years.

The House bill was sponsored by Democratic U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree, who represents Maine’s 1st District, and the Senate sponsor is independent Angus King of Maine.

“I’ve heard from scores of Mainers, including hunters, fishermen, recreational boaters and historical preservationists, who all say that a special designation could help preserve the integrity of the river for generations to come,” King said.

The York River would be the first river in Maine designated as a Wild and Scenic Partnership River, which could lead to federal funding for habitat restoration or other projects.

Established by Congress in 1968, the wild and scenic rivers program aims to protect free-flowing rivers that are deemed to have “outstanding natural, cultural and recreational values.”

The Allagash Wilderness Waterway in far northern Maine is designated as a Wild and Scenic River, a different federal classification that comes with restrictions on development.

So-called partnership rivers are a subset of the program and are managed through a partnership of adjacent communities, state government and the National Park Service. The designation does not prohibit development along the river or give the federal government control over property.

Donnelly, who lives near the river in York, says the waterway has all the qualifications. Around 2000, she began gathering people to form Friends of the York River, a small but passionate group that has long advocated for protection of a waterway that members say is vulnerable to development because it’s just an hour’s drive north of Boston.

When Donnelly and others learned about the Wild and Scenic Rivers Partnership, they decided to push forward with trying to get the York River considered. Pingree first introduced a bill three years ago. It passed in the House but died for lack of action in the Senate. She reintroduced the bill last year, and King introduced a companion bill in the Senate.

And it was with that support that a tiny river at the southern tip of Maine got the attention of Congress.

SUPPORTING JOBS, WILDLIFE HABITAT

“I think people would be astounded at what exists with the York River and the watershed. This is a river that starts up at York Pond in Eliot and weaves its way through the southern Maine landscape for 11 miles to the sea at York Harbor,” said Paul Dest, director of the Wells Reserve. “It’s a remarkably clean, free-flowing river system, which is unusual here in southern Maine.”

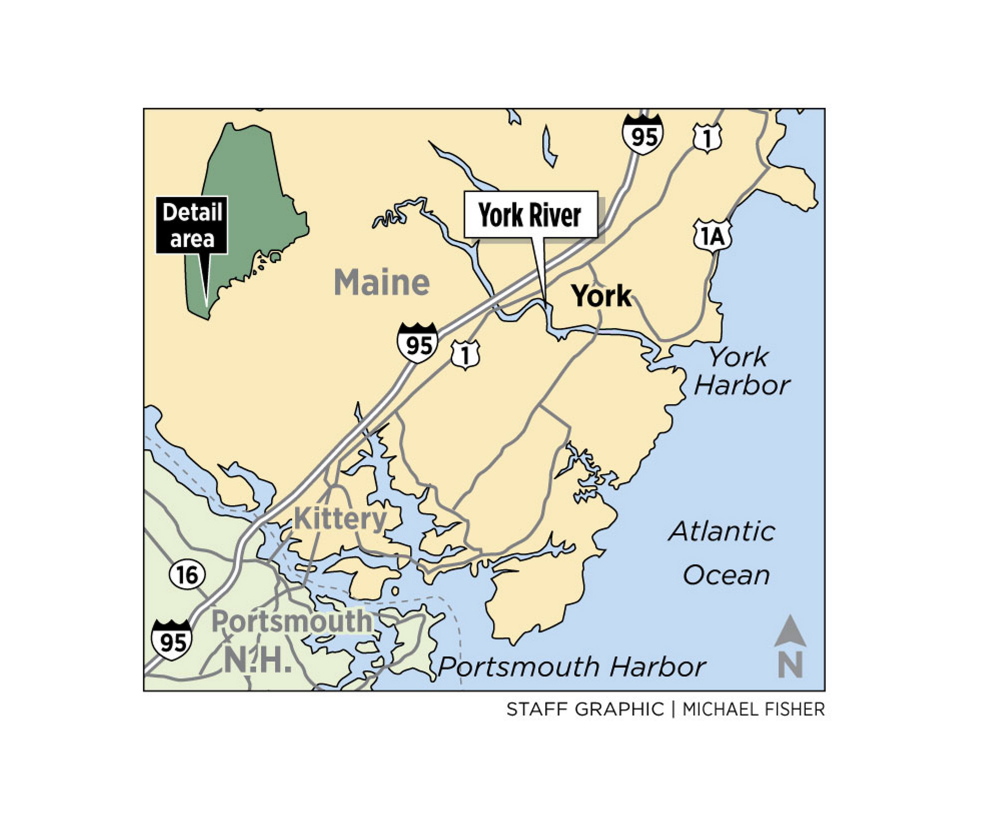

The river and its watershed flow through York, Kittery, South Berwick and Eliot, but mostly in York. The river runs from York Pond past rolling hills, farm fields and salt marshes to York Harbor.

It’s used by commercial and recreational fishermen, including more than a dozen full-time lobstermen who tie up in the harbor. In warmer weather, boaters and kayakers go upstream to areas that are habitats for wading birds, migrating and nesting waterfowl, the endangered box turtle and the threatened harlequin duck. The salt marshes in the watershed serve as a nursery ground for nearly 30 species of fish.

“The York River is a place where people go to work,” Pingree said on the House floor before the vote last week. “Commercial and recreational fishing operations depend on excellent water quality and reliable access to the waterfront. Farmers in the York River watershed grow pumpkins, potatoes and other produce that help keep Maine communities healthy. People travel to the York River to explore and appreciate its natural character and incredible history.”

Pingree is married to S. Donald Sussman, majority share owner of MaineToday Media, which publishes the Portland Press Herald, Kennebec Journal in Augusta and Morning Sentinel in Waterville.

Pat White, a part-time lobsterman who lives next to the river and is a prominent advocate for it, said he would welcome more studies. Of particular concern is the invasion of green crabs and the disappearance of lobsters from the river, he said.

“We need concrete information so we can do more about it,” he said. “This is a hidden treasure in town. I think if we can get this grant money and do some constructive work, we can maintain it.”

A RICH CULTURE AND HISTORY

While the natural and recreational values of the river may be more obvious, its historical and cultural significance is equally important, said Tad Baker, a York resident who teaches history at Salem State University in Massachusetts.

“It’s one of the most historic rivers in Maine,” he said. “The river was the original transportation network in prehistoric and Colonial Maine. As you go along the York River today, you’re going past sites that go back hundreds and sometimes thousands of years.”

Baker said the area around the river has been inhabited for at least 5,000 years. English settlers moved to the area in 1624. Ten years later, the first tidal-powered grist mill in the country – and perhaps North America – was built on the York River, he said.

The McIntire Garrison, believed to be the oldest standing house in Maine, was built along the banks of the river in 1707. In 1902, the author Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, spent the summer living near the river in a home that still stands. Many of York’s 200 archaeological sites recorded in the state’s register are close to the river.

“York is a place with a rich culture and history, and so much of that is focused on the river,” Baker said.

Steve Burns, York’s community development director, sees no downside to pursuing the funding for a study, especially because a townwide vote would be needed to move forward into the subsequent designation stage. Some studies of the river have been done, but more information about the river and watershed could help with future planning and protection efforts, he said.

“This is ideal. Here’s a chance to bring in expertise,” Burns said. “For us, it’s an opportunity to delve a level deeper than we have in the past.”

Gillian Graham can be contacted at 791-6315 or at:

Twitter: grahamgilliangrahamgillian

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story