ALFRED — The story of “Ray and Ray and Charlie and Charlie and George” is one Don Gean has told a million times.

They were five guys in their 60s, worn from years on the streets and living in a homeless shelter in a condemned jail. They would leave the shelter sometimes, but they’d always be back after a day or two, hung over and beat up. They had nowhere else to go.

It was 1985, and Gean was the new director of the York County Alcoholism Shelter. He found himself with a desk in the corner of the dish-washing room and a shelter full of men whose needs went far beyond a bed for the night. He met Ray and Ray and Charlie and Charlie and George – he always rattles off their names in the same order – as soon as he arrived.

Determined to address those needs, find the men a permanent home, and move the shelter out of a crumbling old jail, Gean spearheaded the transformation of the shelter into York County Shelter Programs Inc., an innovative network of programs that now includes mental health and substance abuse treatment, vocational training and a pathway to homeownership.

It is currently serving 400 clients with an emergency shelter, a bakery staffed by program clients, a working farm, housing across York County and the largest on-the-ground solar array in the state. Gean, 71, will retire this month as the program continues to develop transitional and permanent housing, increase its use of solar energy and find more energy efficiencies and revenue sources.

“There’s one word I always think of when I think of Don, and that is visionary,” said Wes Phinney, a former York County sheriff who met Gean in 1985 and now works for the shelter program. “He’s not just a visionary who has ideas; he gets things done. This agency has evolved into a model program when it comes to how you deal with the challenge of homelessness. He is a true activist and advocate.”

TRANSFORMING A HOME

When Gean arrived in Alfred in 1985 with a background in substance abuse services, he found a shelter in distress. The clients were provided with basic meals and a bed, but no support services. The building itself was rundown, with an old cellblock closed off to shelter residents because it contained lead paint. Some shelter residents were alcoholics, but far more had mental health problems that would have been better addressed at the Augusta Mental Health Institute, Gean said.

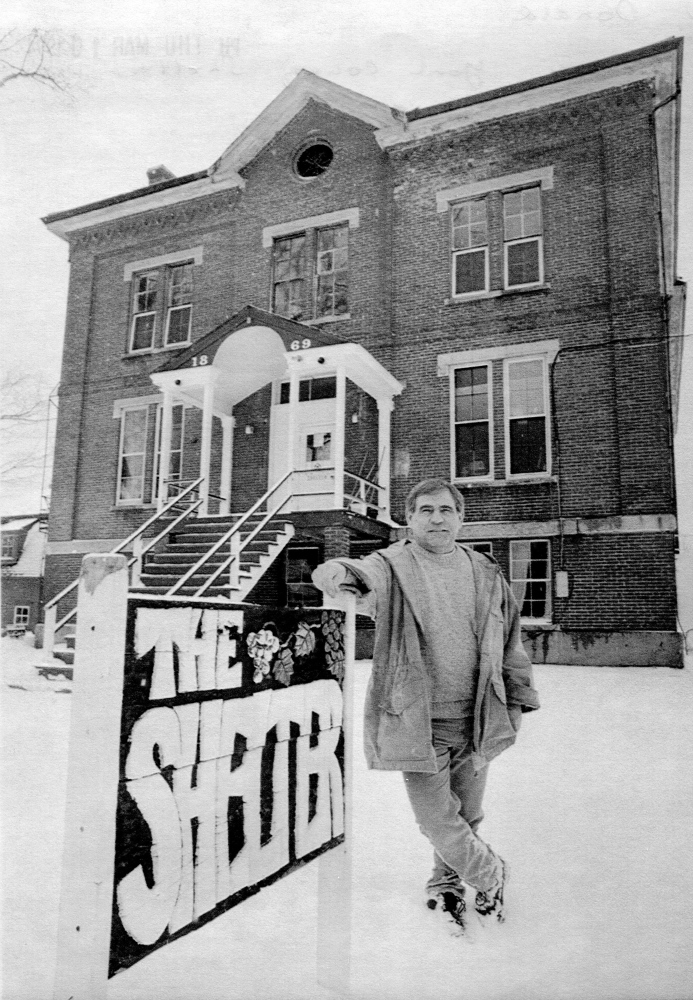

The shelter, in an old brick jail building on Route 111, opened in 1979, the year after inmates had torn it apart during a riot.

“There literally were eight or nine crummy, stained mattresses, some of them on bed frames, some of them on plywood on cinder blocks,” Gean said. “That was the whole program.”

There was no discharge plan for people like Ray and Ray and Charlie and Charlie and George.

“Just providing an overnight bed is not hard. Anyone can fill up an emergency shelter. The trick is emptying the damn thing out,” Gean said. “If you expect to solve the problems that homeless people come with, then you’ve got to address them yourself.”

Gean immediately began making changes in the program, starting with the stale white bread residents ate with bologna for dinner. He headed up to Shaker Hill, where a bakery on the property of the Brothers of Christian Instruction agreed to sell him whole wheat bread.

When he realized the bakery was going to close, Gean took it over as a vocational training site in 1986. He negotiated a lease with the Brothers that included 50 loaves of bread. The payment with bread is an arrangement that is still honored today, with the Brothers keeping a running tally of the freshly baked loaves they pick up.

Gean also turned his focus to providing the treatment services clients needed but couldn’t get on their own, including help for substance abuse, mental health, medical, housing and legal issues.

“That’s when we began to build our own little continuum of care. We figure out who (the clients) are, what the problems are and come up with a plan to solve those problems,” he said. “The goal is to get them out of living here and on to living in a permanent home with the support services going with them, rather than us imagining they’ll be able to find their way back here (for treatment).”

Still focused on getting out of the old jail building, Gean approached the Brothers about leasing an attic space in the building next to the bakery. Using money from bread sales, Gean’s staff transformed the attic into five individual rooms with twisted boards and broken sheetrock from the 99-cent discounted lumber pile at the local hardware store.

The project cost $3,300 and – after many years of sleeping in the condemned jail – Ray and Ray and Charlie and Charlie and George moved into the attic as a permanent home.

“We said if you stay sober, if you take care of this place and pay $200 a month for room and board, this will be your home and you can die here,” Gean said. “The last one – one of the Rays – died here four years ago.”

Gean was able to move others out of the jail, too.

After the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act was passed in 1987, the Alfred shelter was awarded the first transitional housing grant in the nation under the law designed to provide federal money to homeless shelters. That $96,000 was used to build 10 units for adults in the basement of the gym on the Shaker Hill campus.

The shelter eventually took over the entire gymnasium building and moved out of the jail entirely by 1994.

SUSTENANCE AND SUSTAINABILITY

When Gean started out, the shelter had a budget of around $76,000 a year. Today, the program operates with a budget of $5.2 million, according to its annual financial report. Gean is the highest-paid employee, with a salary of $82,000 a year.

The shelter program now has 36 residences, including 15 houses in Sanford and two in Portland. Some of the residents who stay there qualify for Section 8 or federal homeless housing vouchers. Gean said 60 percent of program clients are single adults who do not qualify for MaineCare and face a three-year wait for Section 8 vouchers. Ninety percent of clients have substance abuse or mental health problems, he said.

The shelter’s food pantry, which began after people started asking the bakery for old bread, now serves an average of 65 families a day. It is open to anyone who shows up, no questions asked. Free-meals kitchens in Sanford and Springvale feed another 40 people each day.

The bakery itself continues to serve as a vocational training site for residents, who bake cookies and bread and prepare 110,000 meals a year for the shelter’s programs. The retail side of the bakery is open to the public, with revenue going back into the program.

In the last decade, Gean led a push to provide more transitional and permanent housing and present homeownership as a viable option for formerly homeless clients.

Using $2 million in federal stimulus money from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the shelter program began buying and renovating foreclosed homes in Sanford. Four of those homes are now owned by families who came out of the shelter.

“That was exciting as hell,” said Gean, who first thought about retiring a decade ago. “That was really worth sticking around for.”

Gean also led the program’s focus on sustainability after realizing the organization needed to be more creative with its revenue. He secured special permission from the Public Utilities Commission to use electric heat in its public housing units so they could be heated entirely by electricity generated by a solar array on a farm 20 miles away. Publicly subsidized housing is not normally allowed to use electric heat.

The Angers Farm in Newfield – named for one of the Rays from the original shelter – provides transitional housing for four men and also is a substance abuse treatment center. That solar array – of which Gean speaks often and enthusiastically – sits down the hill from the old farmhouse. The 30 dozen eggs a week from the farm’s chickens are used in the shelter bakery.

The shelter’s recidivism rate, or portion of people returning to the emergency shelter, was 5.3 percent last year for single adults. No families had to return to the emergency shelter in Alfred. Gean said those numbers are extremely low – “mind-boggling” – and show the program is working.

In Portland, by comparison, the city-run Oxford Street Shelter had a 9 percent recidivism rate for residents who had been placed in housing, down from 12 percent the previous two years.

Phinney, the former sheriff, said Gean created a maverick agency that pushed other programs to provide better services to clients.

“He might come across to some people as being socially liberal, but Don has always been a solid, old-school conservative businessman,” he said. “Everywhere you look, this man has created an atmosphere of wanting to be progressive and do things differently.”

A VOICE FOR THE VOICELESS

Even as he led the transformation of the shelter, Gean extended his reach out of York County. He served in the Maine Legislature in the early 1990s and has worked with state and national organizations to address homelessness.

“He is, without question, a warrior for people with substance abuse, mental health issues and homelessness,” said John Sylvester, an Alfred selectman who has known Gean for many years. “He’s fought very hard for a long time to help people who don’t have a voice.”

A natural storyteller whose eyes are framed by laugh lines, Gean built a reputation as a strong leader who advocated constantly for homeless and poor people.

Former Gov. John Baldacci served with Gean on the Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee and later asked him to help lead a statewide task force to end homelessness.

“He was a great leader. He has such a big heart and cares deeply and sincerely for people who are struggling,” Baldacci said, noting how Gean’s wife, Pam, and their six children were all involved with the shelter. “They’re making a difference in a lot of people’s lives in Maine.”

Grady Collins, who met Gean after arriving at the Alfred shelter in 2007, said Gean has created an agency that transforms people’s lives – including his own.

Before Collins, 53, found the shelter, he was couch-surfing and struggling with problems he is now reluctant to talk about publicly. He stayed in the dorm at the emergency shelter for four months before moving into a single room and later an apartment.

In 2009, Collins became one of the first clients to buy a home through the program. He said he never imagined he’d be a homeowner.

“I felt I wasn’t worthy at first, but the staff at the shelter reassured me that I was,” he said.

Collins, an artist, now serves on the board of directors for the Nasson Health Center in Sanford, a position Gean encouraged him to pursue. He also volunteers at the shelter and checks in regularly with his caseworker.

“This is a lifesaving organization,” Collins said. “(Gean) is a big part of saving people’s lives, but he won’t tell you that. He’ll take no credit.”

FRUSTRATION, AND FINDING A WAY

Gean has spent three decades fighting to address homelessness, and he still sounds like a fighter.

“That’s a part of what makes this worth doing. The folks we deal with get all the blame and damn near none of the credit or resources. That’s unfair,” he said. “It’s kind of fun to get up in the morning still pissed off about that.”

He admits he sometimes sounds cynical when he talks about politics and homelessness. There are times he is frustrated when he sees programs with too much bureaucracy that use the same model over and over, without much success.

“If you take them in at night and throw them out in the morning, you’re kidding yourself that they’re going to get better,” he said.

But Gean also sees progress, especially in Alfred. When he first took over at the shelter, town residents were holding meetings about the shelter clients. The locals wanted them to wear sandwich boards that identified them as shelter residents. Now, many of the shelter’s 500 volunteers are from Alfred.

“I got to build something that was different, unique and that was working,” he said.

Gean’s decision to retire has been a long time coming. He first started talking about it when he was 60 and, 11 years later, is finally ready to spend his winters in the mangrove swamps of Florida.

And now is a time when the program is especially strong, Gean said. The shelter program is in talks with the Brothers about buying the Shaker Hill property, an effort Gean will assist with even after he retires.

Gean recently spent a day reflecting on his 30 years at the shelter and the rundown jail where it all started. For the first time in 20 years, he stepped into the old jail, part of which is now used as an antique store.

Gean walked slowly through the upper floors, marveling at how much has changed – and how much hasn’t – since the shelter moved to Shaker Hill. The floors were covered with a thick layer of dust and the paint peeled from the walls in large curls, but it’s not a whole lot worse than when people lived there, Gean said. In a small bedroom, Gean stopped to talk about one of his first encounters with Ray Angers, who lived alone in that room and was resistant to Gean’s decision to give him roommates.

“He told me he’d kill me if I ever made him move or get roommates,” Gean said. “I told him to hurry up and do it because you’re getting roommates.”

For Gean, the story of his career always comes back to Ray and Ray and Charlie and Charlie and George.

In all of his years at the shelter, Gean has been careful to keep a professional distance from the clients, something he says is essential to survive in a place where you could easily be overwhelmed by the emotional weight of it all. He knows many of the clients and greets them with handshakes and smiles. He advocates for them, cheers for them and always puts their needs first, but never develops a personal relationship with them, he said.

Even when it came to the five guys who were there from the beginning.

“I’ve known Ray and Ray and Charlie and Charlie and George about as long as I’ve known my kids. I never developed a personal social relationship with any of them,” he said. “Not an Easter went by that we didn’t talk about sneaking Charlie over for dinner, but we never did. I don’t think you can and survive here long. It’s not about us feeling better.”

That may have been the hardest part of his job. But, Gean said, making himself feel better still doesn’t matter.

Ray and Ray and Charlie and Charlie and George always came first.

This story was updated March 16, at 3:40 p.m. to correct the name of the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act.

Gillian Graham can be contacted at 791-6315 or at:

ggraham@pressherald.com

Twitter: grahamgillian

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story