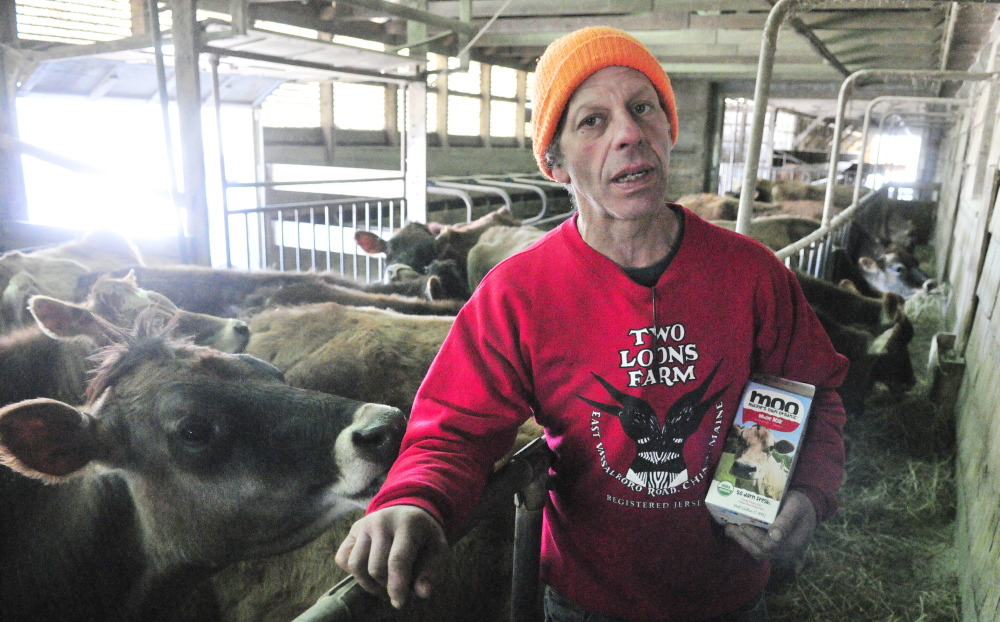

SOUTH CHINA — As he stood next to 600- and 800-gallon bulk tanks filled with raw milk, Spencer Aitel said he believes his farm is part of the fabric of the community.

While waiting last week for a truck from Maine’s Own Organic Milk to pick up his farm’s every-other-day shipment, he described his dairy operation and the 150 cows at Two Loons Farm. Built in 1959 when the farm sold milk to a company in Augusta, it’s a recent addition to the collection of a dozen farms at the organic milk company.

Aitel said his 550-acre South China farm joined the cooperative last year because of a shared goal: creating a sustainable business model to allow Maine dairy farms to succeed.

“We’re also providing a lifestyle that a lot of people desire,” Aitel said of the organic dairy company. “It’s nice to drive down and see cows in your neighborhood. And that’s fast disappearing.”

Aitel and his wife, Paige Tyson, owners of Two Loons Farm, left Wisconsin-based Organic Valley for MOOMilk in September after investors gave an additional $3.9 million to the group of 12 farms located throughout Maine. Aitel said the investment, which was made through members of a network interested in supporting local foods systems called Slow Money Maine, gave them confidence that the start-up would have enough financial stability to make the risk worth it.

MOOMilk launched in 2009 after HP Hood Inc. dropped 10 Maine dairy farmers as an LC3, a special form of corporation that limits profit and has a social cause. Its brief existence has been rocky and uncertain at times, nearly shutting down in 2009 after running out of cash, but the latest round of investment stabilized the company’s finances and allowed it to invest in its marketing program with a new design for its cartons and an updated website highlighting all its farmers. The new packaging features photos of different cows for each of its five products, including a new chocolate milk.

SIX MORE FARMS

The investment will also allow the company to add another half-dozen farms by the end of the year, said MOOMilk CEO Bill Eldridge.

The low-profit, limited liability company distributes to more than 200 grocery stores throughout New England, including Hannaford, Shaw’s and Whole Foods. It most recently expanded to additional stores in the Boston area, Rhode Island and Connecticut.

“It’s amazing that people as far away as Connecticut and Rhode Island think highly of our milk and support it and treat it just like it’s local milk,” Eldridge said.

When MOOMilk started, it was distributing around 2,000 gallons a week to Maine, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, Eldridge said. He declined to say how much the company distributes now, but he said sales doubled each year between 2011 and 2013.

‘REALLY FAST GROWTH’

“Obviously, that’s really fast growth, and you can only sustain that for a certain amount of time,” Eldridge said. He predicted that the company could continue doubling its sales each year for the next two or three years.

The company trucks milk from its farmers as far north as Aroostook County to Smiling Hill Farm in Westbrook for processing and packaging. The product ends up on the shelves of stores between two and three days of its being produced, Eldridge said.

Being a fresh product, however, limits how far MOOMilk can distribute. Eldridge said the outer limit is likely the Greater New York City market, which the company expects to reach sometime this year. The company also began selling its products wholesale two years ago to companies that make ice cream and gelato, yogurt and cheese. Its ingredient customers now represent 20 percent to 25 percent of total sales, Eldridge said.

Aitel, one of the company’s newer farmers, said MOOMilk’s market and size will hopefully allow individuals or couples to start their own dairy farms. He and his wife previously considered building a processing plant to distribute their own milk, Aitel said, but they couldn’t make the numbers work. They wouldn’t have been able to produce enough milk to justify the capital investments needed, he said.

Aitel said the farm previously supplied milk to Organic Valley and The Organic Cow of Vermont, which later became Horizon Organic.

Those two milk processors, along with Aurora Organic Dairy, control a vast majority of the organic milk market, said Mark Kastel, co-director of The Cornucopia Institute, an organic agriculture research organization in Wisconsin. The rest of the organic milk market is made up of a handful of regional producers like MOOMilk and individual farms that process milk themselves, Kastel said.

Two Loons Farm, which features the oldest house in the town of China, was receiving as much or more for milk by selling to Organic Valley, Aitel said, but MOOMilk offered a chance to grow a company more aligned with their mindset and goals.

“We’re hoping to come up with a system that works well enough that we can demonstrate that this farm would be worth the next generation pursuing,” he said.

DAIRY FARM DECLINE

The number of commercial dairy farms in Maine dropped by more than half between 2001 and 2013, from 645 to 304. The decline slowed in 2004 and 2005, however, after the state created a price stabilization program that established a safety net price for Maine farmers based on the cost of producing milk in the state, said Julie-Marie Bickford, executive director of the Maine Dairy Industry Association.

But in the last 18 months, the state lost another 30 or so dairy farms for a variety of reasons, often as a result of rising grain and feed prices, Bickford said.

“Even though the price that farmers were getting paid for their milk was a decent price, the expenses far outpaced what they were receiving for the milk,” she said.

The federal government sets the minimum price farmers get for their milk with complex formulas based on how much dairy product is shipped and sold on the global commodity market. The Maine Milk Commission, part of the state Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, can raise the price Maine farmers receive based on the expected cost to produce it.

Organic milk, like MOOMilk, typically commands prices above the minimum level, so organic dairy farms can negotiate contracts for how much they will receive from a distributor for their product, Bickford said. That means there is less volatility in the price farmers receive, which can fluctuate month-to-month for conventional operation.

The higher prices also hit the customers. For instance, a half-gallon carton of MOOMilk whole milk cost $3.99 at a Hannaford in Augusta, compared to $2.39 for a half-gallon of Hood.

FOLLOWING GUIDELINES

Farmers using organic methods, totaling roughly 20 percent of the dairy farms in Maine, must follow guidelines from the certifying agency, like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which includes allowing cows to graze, using organic feed and not treating the animals with drugs like antibiotics or growth hormones.

Besides high feed prices, Bickford said another reason for the recent closures is that some farms with owners who had retired or died didn’t have a next generation or other farmers ready to take over operations.

Farm succession – transferring the operation to a younger generation of farmers – can be challenging if an older farmer doesn’t want to give up the reins, Bickford said. She said the hope is farms will be transferred to new ownership because it’s difficult for new farmers not already in the industry to start such a capital-intensive venture from scratch.

Aitel said succession is made more difficult for dairy farms that have seen their herds and physical assets deteriorate by not bringing in enough money to sustain the operation. When that happens, there isn’t much a farmer can do, he said.

“What do you got left? You’ve got a dairy that’s about to close, and no one’s ever going to be there again as a dairy farm,” Aitel said. “So we’re hoping to avoid that, and we’re hoping that at least some of what we do makes it so others will follow.”

Paul Koenig can be contacted at 621-5663 or at:

pkoenig@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @paul_koenig

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story