SCARBOROUGH — Town Manager Tom Hall readily admits that social media isn’t his thing.

His wife and his kids, ages 16 and 20, use Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat. But so far, Hall has avoided jumping into the social media stream. Until now.

One of Hall’s goals for 2015 is to establish Facebook and Twitter accounts for Scarborough’s municipal government, following in the footsteps of its police, fire, public works and community services departments. Even the Scarborough Public Library has a Facebook page that is “liked” by 423 people.

Hall’s plan to dive into social media is part of an ongoing effort to promote civic engagement and increase the transparency of what happens at Town Hall.

“The reality is, more and more of society is consuming information through social media and electronic means,” Hall said. “If we’re not plugging into that system, we’re missing them.”

Hall is one of an increasing number of municipal officials in Maine who are responding to growing demand that local government agencies improve and expand their Web presence, especially through social media. They’re dedicating staff time and financial resources – and dealing with the challenges of creating an open forum and inviting comments from community members – all in the interest of increasing public access to municipal information.

Some of Maine’s Web-savvy public officials include a Windham school superintendent who used Twitter to put the community at ease during a three-day crisis and a Bangor police sergeant whose witty Facebook posts have attracted an international following and can help identify a shoplifting suspect in minutes.

Among Maine’s 492 municipalities, more than 200 have websites and more than 50 of them are using social media to communicate with their constituents, said Eric Conrad, spokesman for the Maine Municipal Association. The most noteworthy growth is in social media.

They’re using it to inform townspeople about trash-collection changes, development proposals and public safety emergencies. They’re posting travel advisories related to foul weather, traffic accidents and public works projects. In the process, they’re generating broader interest in community affairs and humanizing public employees who otherwise might have little day-to-day contact with the people they serve.

“Through the power of social media, municipalities can put out information to hundreds or even thousands of followers and have a reasonable expectation that they will share it with hundreds or thousands more,” said Conrad, who runs the association’s social media training program.

Conrad said social media cannot replace other forms of official communication, and there are risks associated with using it for government purposes. But municipal officials can minimize problems by developing plans and policies to manage social media for maximum benefits.

That’s the approach in South Portland, where several town departments have Facebook pages or Twitter feeds, including police, fire, public works, economic development and parks and recreation.

City Manager Jim Gailey has his own Twitter feed – @sopomanager – which he started in June 2013. He “tweets” and “retweets” information and news links of interest to his 171 “followers.” Much of the information he tweets comes from 48 people or agencies that he’s “following,” including news sources. Recent tweets have been about a city employee winning an award, a yacht fire on the waterfront and the last week of Christmas tree collection.

“It’s a way to push out information,” Gailey said. “We had heard from people that the city didn’t do a good enough job promoting itself. So this is one way to address that. It always surprises me how many people see my tweets. It seems to be beneficial. I’ll keep doing it as long as it is.”

CRISIS MANAGEMENT

Sanford Prince, superintendent of Regional School Unit 14 in Windham and Raymond, experienced the effectiveness of social media when emailed threats closed the district’s eight schools for three days in mid-December. Prince used his Twitter feed, which he started in July and linked to the district’s website, to help keep parents, students and others informed.

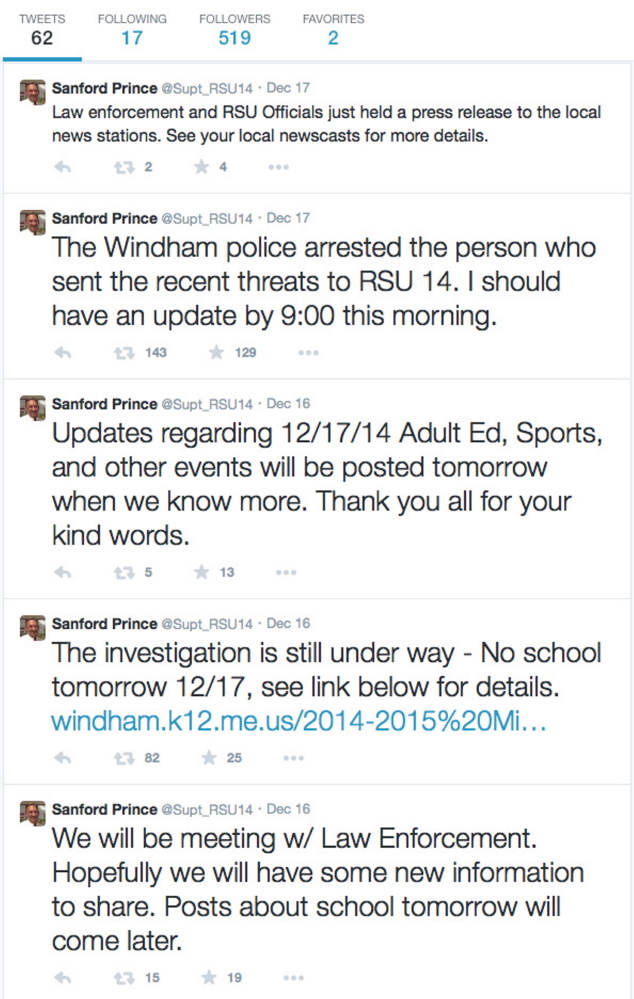

In addition to sending emails to parents and communicating regularly with news media, Prince issued brief updates under his Twitter handle, @Supt_RSU14. He started with this notice at 7:34 a.m. on Dec. 15: “This morning we sent all schools home as a precautionary measure after a threat was received. Police are investigating – more info to come.”

That tweet was “favorited” three times and “retweeted” five times – actions that either acknowledge or forward the information to others. At the time, he had 44 Twitter followers.

All told, Prince posted 14 tweets during the school shutdown, peaking with this news-breaking post at 4:28 a.m. on Dec. 17: “The Windham police arrested the person who sent the recent threats to RSU 14. I should have an update by 9:00 this morning.” That tweet was favorited 129 times and retweeted 143 times. A 16-year-old student who lives in town but attends school elsewhere was charged with felony terrorizing.

By the time Prince posted final tweets welcoming students back to school and thanking staff and parents for their support, he had more than 500 Twitter followers. In the wake of the crisis, parents, staff and students were effusive in their praise for how the school district handled the threats and kept them informed.

“It became a necessary tool,” Prince said. “It’s amazing how rapidly you can disseminate information, and with that crisis going on, I think people liked hearing that we were tackling things head on.”

Prince doesn’t tweet a lot – he’s posted only 62 tweets since July – but he plans to do it more regularly.

“I see it as a way to keep people informed about good things that are going on and to establish a brand for our district,” Prince said.

FACEBOOK BENEFITS

An early user of social media in Maine is the city of Ellsworth, which launched municipal and police department Facebook pages about four years ago, said City Manager Michelle Beal, who is the municipal association’s president.

Ellsworth’s municipal page is “liked” by more than 1,500 people, who see information posted by city staff members in their Facebook news feeds. The police department’s Facebook page is “liked” by more than 11,000 people. In a city of fewer than 8,000 residents, that’s a strong following, in part because Ellsworth is a service center to surrounding towns.

“It is extremely useful,” Beal said of Facebook. “If you’re trying to be transparent, if you’re trying to get information out, if you’re trying to get feedback on a proposal, whatever – it really succeeds in a way that can be very helpful to us.

Beal sees the benefits of Facebook regularly through Web analytics that show how many people see the city’s postings. Last week, a city employee who manages the municipal page posted a public invitation to an upcoming open house at a new community center.

“Within 24 hours, more than 1,500 people had looked at it,” Beal said.

Despite obvious benefits, some municipalities are reluctant to dive into social media. While Yarmouth officials anticipate upgrading the town’s aging website, the idea of interacting with citizens through a municipal Facebook page or Twitter feed is overwhelming.

“We don’t have the resources to monitor it for false or disparaging comments and we’re scared to death of being accused of trying to influence the outcomes on issues facing the council,” Town Manager Nat Tupper said.

The Maine Municipal Association’s training program helps public officials decide whether to have interactive or broadcast-only social media accounts, develop social media plans and policies, and address First Amendment issues such as free speech, defamation, libel, public records and copyright infringement.

JUST DUCKY

Several police departments in Maine have significant Facebook followings, including Westbrook (12,438 likes), South Portland (7,941) Portland (7,262) and Lewiston (5,506). Even in small, coastal Ogunquit, which has fewer than 1,000 residents, the police department has more than 3,100 Facebook followers, who no doubt appreciate the postings of crime-suspect descriptions, weather warnings, lost-dog notices and beautiful beach photos.

Topping the social media heap in Maine is the Bangor Police Department’s Facebook page, which has nearly 39,000 likes from people all over the world. Its following skyrocketed from about 9,000 last July, after a story about the department’s witty, rambling posts – including photos of its unofficial mascot, a stuffed “Duck of Justice” (DOJ) – was picked up by national news outlets.

The person responsible for the spike is Sgt. Tim Cotton, a 26-year police officer who took over media relations when he was promoted last June.

“I write things that I think are humorous because I know I wouldn’t want to read a police page that was boring. Police officers in general are a humorous bunch,” said Cotton, who worked in radio before becoming a police officer.

As a practical tool, Bangor police regularly use Facebook to help solve crimes. Whenever they have a photo or a video of a suspect, often taken from a security camera, Cotton posts it on Facebook with a description of the person and the crime. Last week, Cotton posted photos of a shoplifting suspect leaving J.C. Penney at the Bangor Mall.

“Twenty minutes later, three people had called and we had a name,” Cotton said. “The more followers we have, the better chance we have of finding people.”

Bangor police also use Twitter, though Cotton finds he’s constrained by the 140-character limit, and the department recently joined Instagram to target younger followers.

“We’re connecting with people who use social media,” Cotton said. “This is a conversation between us and our constituents; between us and the people who pay our salaries. It opens up a dialogue that we wouldn’t otherwise have. It’s a big public relations tool. We’re still going to arrest you if you do something wrong, but it does humanize us.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story