A dispute that erupted last week over Portland’s use of state funds at its homeless shelters may have caught many by surprise. But it was nearly 30 years in the making.

The financing of the city’s emergency shelters, as it turns out, was also a hot political issue in the 1980s, culminating with protest encampments in Portland’s Lincoln Park and in the plaza outside City Hall. And it was a 1985 state audit – similar to the audit that triggered the political clash last week – that led to the creation of a “special billing arrangement” to allow the city to finance its shelter for the homeless.

That financing arrangement between the city and the state was challenged and revisited numerous times over the years. And last week it became the latest flash point in a high-stakes political clash between Portland and the LePage administration over welfare reform and state support for the city’s social safety net.

The administration issued an audit report Feb. 20 that accuses the city of not following proper procedures for the use of state funds that are intended to help people with no money. In fact, the report noted, the city charged the state General Assistance program for thousands of bed nights used by 13 people who each had at least $20,000 in bank accounts.

City officials argued that they were following state-approved billing practices. And homeless advocates said the finding highlights the lack of services for people incapacitated by mental illness, including those who have money in the bank.

The clash over the audit is long from over, and Portland now gets an opportunity to answer by submitting additional information.

The outcome could be costly for the city, although it’s unknown how much state funding might be withheld. In fiscal year 2014, the state paid for all but $28,000 of the $2.7 million cost to run Portland’s two shelters and overflow facilities.

But the audit report has already been swept up in the larger dispute over Portland’s General Assistance spending, which has nearly doubled since 2009 and now consumes more than half of Maine’s GA funds.

Along with challenging the shelter financing, the administration wants to cut off state aid for the fast-growing number of immigrants in Portland who are awaiting asylum. And it wants to change the way state General Assistance funds are distributed in a way that would shift more than $4 million in annual state funding away from Portland.

‘SPECIAL BILLING ARRANGEMENT’

In the mid-1980s, Portland had one homeless shelter with 53 beds. While Portland’s two city-run shelters now have capacity for about 250 people – and they regularly overflow – some of the issues were the same then as now.

Throughout the 1980s, the state was reducing the size of its mental health institutions, which effectively put more people with mental illness onto the streets. Many ended up in homeless shelters. By 1990, half of the people sleeping in the city’s Oxford Street shelter had mental illnesses and staff expressed concerns about psychotic behavior.

Unable to accommodate the demand, the city was forced to place people seeking emergency shelter in hotel and motel rooms at substantial costs to the state. The city expanded its shelter capacity in the late 1980s as a way to keep people out of hotels and reduce costs, according to city documents.

Around the same time, in response to the 1985 audit of Portland’s GA spending, the city and state formed the “special billing arrangement” to help pay the costs of its shelter system, according to a May 17, 1991, letter to the state from Robert Duranleau, the former director of the city’s social services division.

General Assistance is emergency aid provided to people who have inadequate income and no savings to provide basic necessities to maintain themselves or their families, including emergency shelter. Maine law requires cities and towns to provide the aid based on standard eligibility criteria, and the cost is shared by the municipalities and the state.

However, the city of Portland contends that the arrangement made in the 1980s effectively allowed it to charge the state’s GA program for the total operating costs of its shelter, rather than only for those users who meet financial eligibility requirements.

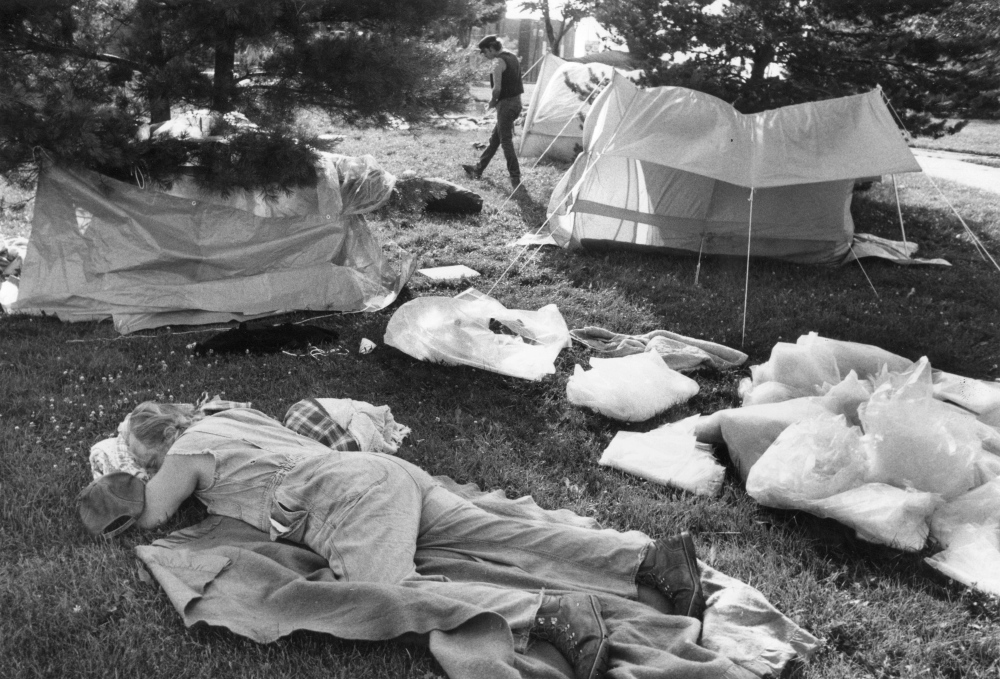

The homelessness crisis that coincided with the billing arrangement came to a head in the summer of 1987.

Homeless people set up an encampment in front of City Hall, and eventually moved to nearby Lincoln Park, to protest the closure of a private shelter. Robert Ganley, who was Portland’s city manager at the time, initially resisted the demands of protesters to open a new shelter, and even threatened to arrest protesters if they did not leave their encampment.

The standoff ended more than two weeks later when Mitch Snyder, a nationally known Washington, D.C., activist, was flown to Portland to negotiate with Ganley.

Ganley vowed that Portland “would do its part” to ensure no one seeking shelter in the city would be denied. The shelter that ignited the protest eventually reopened with city funding.

AN ISSUE COMES FULL CIRCLE

One of the people in the middle of that homelessness crisis was Michael Brennan. The man who is now mayor was then the local United Way director of community initiatives.

“The discussion at that point, which I think is still true today, is that we don’t want anyone in the city of Portland to be without a place to stay,” Brennan said.

Brennan went on to serve on the city’s Emergency Shelter Assessment Committee, which was established to monitor the needs and availability of shelter beds.

On July 16, 1987, the group drafted a statement on homelessness in the city which acknowledged that people who did not qualify for GA were being excluded from the shelter network. They recommended setting aside 25 percent of all shelter beds and waiving admission requirements for those who don’t qualify for GA.

In 1989, the Maine Legislature amended the state’s GA statute to allow municipalities to presume someone who seeks emergency shelter is eligible to receive GA.

As the shelter system expanded, the city’s practice of using “presumptive eligibility” and drawing on state GA funds for its shelter costs was challenged by the administrations of Republican Gov. John McKernan in 1991 and independent Gov. Angus King in 1995.

McKernan’s administration eventually came around to the city’s argument.

“We agree that your billing system for shelter expenses is adequate and appropriate,” wrote Richard Morrow, the state director of social services.

The city was unable to provide documentation detailing how King’s challenge was settled.

However, Danielle West-Chuhta, the city of Portland’s corporation counsel, said the record clearly establishes the fact that Portland’s program was repeatedly found in compliance since then. She provided recent audit compliance letters from 2008 to 2013, including two letters from the LePage administration.

Maine Health and Human Services Commissioner Mary Mayhew did not know what type of information was examined during previous audits that determined Portland’s program to be in compliance with state statutes, including two that were issued by the LePage administration.

“The reviews are based on information that is provided at that time,” Mayhew said. “We have additional information that has been provided by the city (as part of) this recent review.”

PROVISION DESCRIBED AS ‘AMBIGUOUS’

Both the state and the city are citing a legal opinion drafted in 1996 by Assistant Attorney General Christina Hall, who served under King, to support their interpretations of what Hall described as an “ambiguous” provision in the General Assistance law. The intent of the provision, enacted in 1989, was to permit “municipalities to presume that persons served by emergency shelters are eligible for general assistance,” she wrote.

Jennifer Thompson, a city attorney, argued in an April 18, 2014, letter to the DHHS that the statute does not explicitly require the city ever to determine whether someone is eligible to stay at a shelter funded through GA. “The language says only that presumptive eligibility is permissible – with absolutely no limit on the application of that presumption,” Thompson wrote.

The state, however, argues that the city can only be reimbursed for the bed nights used by people who qualify for GA based on financial need. It argues that presumptive eligibility can only be used temporarily when someone seeking assistance cannot fill out a full application because of the time of day or extenuating circumstances. Shelter residents are expected to do so before the city can submit a reimbursement request, the state argues.

“Reading the statute as Portland apparently does violates all rules of statutory construction and would lead to absurd results,” the Feb. 20 state audit claims. To argue that the law “provides limitless assistance without ever requiring an actual determination of eligibility would ignore the legislative intent, create inconsistent rules, and lead, finally to absurdity.”

Hall, the assistant attorney general under King, noted the ambiguity of the language but concluded that the legislative history supports a stronger argument that “shelter residents must apply and be found eligible for GA in order for towns to be reimbursed for costs attributable to them.”

MENTAL ILLNESS FACTORS

While the legal dispute focuses on the use of General Assistance funding for shelter residents who don’t qualify, advocates for the homeless say the conflict highlights the fact that the longest stayers in homeless shelters are people with mental illness who cannot care for themselves, whether they have money in the bank or not. And they attribute that problem to the state’s failure to adequately fund the community-based mental health programs that were supposed to treat patients who were released from mental institutions in the 1980s.

“The state has not lived up to its responsibility to help people with severe mental illness,” said Mark Swann, the executive director of Preble Street, a Portland nonprofit that provides assistance to the homeless.

Some also point to the state’s successful efforts to trim the number of people who receive health coverage through MaineCare, the state’s Medicaid program. The state’s elimination of eligibility for childless adults in 2014 left hundreds of people without treatment options for their substance abuse or mental health issues, advocates say. City shelters saw an increase in the number of people with mental illness turning to the shelter system, said Jon Bradley, associate director of Preble Street.

Jenna Mehnert, executive director of the Maine chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, said state grants for community-based health services also have been reduced over the years.

“There is no place else to turn,” she said. “Homeless shelters are carrying the weight. Them and jails.”

Mayhew, the DHHS commissioner, pushed back against that notion. She said the state has sent more than $4 million to Portland since 2010 to house people with mental illness and substance abuse issues, including $900,000 for Florence House, a permanent supportive housing complex for women. She noted that LePage’s budget proposal includes $14 million over the next two years to help people with mental illness.

“We certainly understand the challenges of homelessness throughout the state,” Mayhew said. “No one is suggesting that these individuals should not have access to the homeless shelter. This is simply about how those costs are budgeted and paid for.”

HEATED POLITICS OF WELFARE REFORM

The clash is playing right into the heated politics of welfare reform in Maine.

LePage’s message of welfare reform – particularly cracking down on waste, fraud and abuse – resonated with voters last year, paving the way for his re-election in November. LePage’s office issued a statement Friday using the audit of Portland’s shelter program to justify other budget proposals that would cut sources of state revenue to municipalities.

“Municipalities complain about losing revenue sharing, but then I see abuse like this. … It’s hard to have sympathy for them,” LePage said.

But such rhetoric oversimplifies a complex issue and ignores strides being made to address the root causes of homelessness and poverty, advocates say.

“Those simple messages about fraud and people abusing the system really clouds the issue,” said Bradley, of Preble Street.

For example, advocates say, the state audit report did not consider that the longtime shelter residents with money in the bank were people who suffered from mental illness and either did not have legal access to their money or the wherewithal to use it responsibly. Nor did the audit disclose that those individuals were sleeping at the shelter in November 2013, but were no longer there in January when the audit occurred.

Dawn Stiles, Portland’s health and human services director, said the individuals highlighted in the audit were no longer in the shelter and were likely placed in permanent housing as part of the city’s efforts to end homelessness.

The city is appointed to manage the finances of roughly 400 homeless people, or less than 10 percent of the shelter population, Stiles said. Most have balances of less than $1,000 and a few have as much as $2,000. She said only one person has at least $6,000 and another has $12,000.

Today, Stiles said, “there are no high-worth individuals staying at the shelter.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story