More than its airy classrooms, wooded trails or expansive windows, the greatest advantage at the new Friends School of Portland will be what the building lacks: utility bills.

When construction is completed this summer, the Friends School of Portland will become the first school in Maine to attain a rigorous set of building efficiency standards, known as “passive house” status, that means it will be able to dispense with nearly all of its energy costs. Instead, it will rely on a combination of solar power, modern heating techniques and construction methods so tight that the body heat generated by the school’s 120 occupants was factored into the design.

“It’s an incredible gift that this board has given to the future of this school to have a completely predictable operating cost,” said Naomi C.O. Beal, chair of the Friends School’s building committee, and also the director of PassivhausMAINE, a group that promotes the building technique in the state. “For a private school operating on a margin, that’s a big piece.”

Although only two other schools in the nation and a handful of private homes in the state have reached the “passive house” level of efficiency, planners and architects who designed the school expect the methods to become more widespread in the United States in the future.

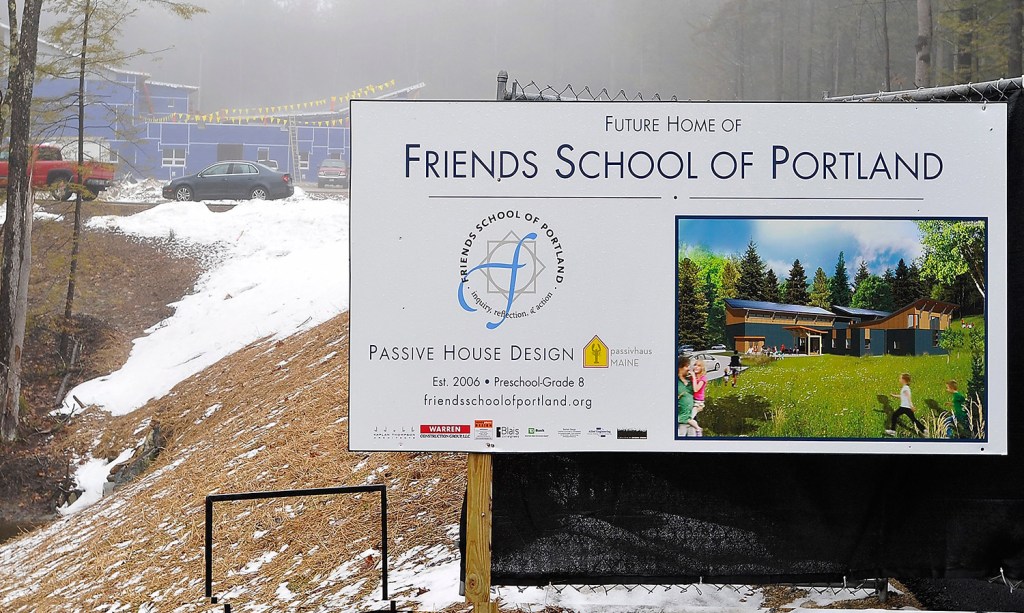

The roughly $2.5 million school project is the result of three years of fundraising by school boosters and two years of planning by architects and designers. The result will be an angular 15,500-square-foot structure with half a dozen classrooms, art and music space, administrative offices and, for the first time, a large, indoor area to host the school’s Quaker meetings.

The new building stands on 22 wooded acres in Cumberland off Route 1, meaning students and staff will say goodbye to their current home on Mackworth Island, where the school has rented space since it was founded in 2006.

While energy-efficient structures built into hillsides or underground – or those using turf as a natural building material – have existed for centuries, research into passive structures emerged in Germany in the late 1980s and early buildings in the style were constructed in the early 1990s.

Since then, the methods have gained traction throughout Europe and especially in Nordic countries, where environmental consciousness and a desire to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and energy use have driven some of the largest passive developments in the world.

Modern passive structures can look identical to any other home, office or school, but what makes them unique is what’s hidden under the walls, floor and ceiling.

Thick layers of insulation are packed behind every surface.

Underneath exterior shingles and clapboards are layers of specialized sheathing, similar to thick plastic or rubber, that keep moisture and air from getting through.

Sealing the gaps are wide bands of construction tapes, designed to stick to all kinds of materials and replace caulking or other liquid fillers that have long been traditional sealants.

The windows are triple-glazed and the casements are designed to be virtually leak-proof, said Peter Warren of Warren Construction Group, which is building the school.

Closing the gaps leaves no place for heat to escape or cold air to creep in. Air is circulated at a steady rate by ventilation systems that recover leftover energy from the outflow.

“It is a whole new way of looking at construction,” said Phil Kaplan of Kaplan Thompson Architects, the Portland firm that worked on the project.

A heat pump system powered by a 40-kilowatt solar array on the school’s sloped roof will keep the rooms at specific temperatures.

Although the specialized building materials and construction techniques are important to achieving such efficient operation, other gains are baked into more elemental aspects of a building’s design, Kaplan said.

Using equipment to model the position of the sun at any time of year and the shadows cast on the site by the surrounding foliage, Kaplan said the designers had to select, one by one, which trees to clear and which to keep, in order to maximize the use of the sun’s energy to heat the building naturally.

Head of School Jenny Rowe said students will learn about how the school was constructed and how the principles behind it align with the larger Quaker philosophy “to take care of each other, (and) to take care of the land,” Rowe said. “It’s a very obvious outgrowth.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story