Conner Comeau’s crime was spraying graffiti on rail cars at a South Portland train yard in 2010. For that, he was sentenced to 48 hours in jail.

But the far more serious punishment came in 2014, when Comeau, 25, missed two payments on the $1,300 in restitution the court ordered him to pay. He ended up in jail for 100 days, earning credit at a rate of $5 each day toward paying off his debt.

Taxpayers in Maine are spending at least tens of thousands of dollars a year – and likely much more – to jail low-income defendants like Comeau who failed to pay the fines for what are often minor crimes, according to a study of Maine’s jails conducted by the American Civil Liberties Union of Maine. In all of these cases, it costs taxpayers more to jail the defendants for unpaid fines or restitution than the inmates can earn in credit for each day they serve behind bars.

Comeau’s 100 days in jail, for instance, cost taxpayers roughly $11,200. The state recouped none of the cost, according to Cumberland County Sheriff Kevin Joyce.

“It’s a $107 deficit per day,” Joyce said, noting that it costs him $112 each day to house each inmate at the jail in Portland, but Comeau only paid off his debt at a rate of $5 per day. “I can lock up everyone if they want to pay for it, or I can lock up no one if they don’t want to pay for it.”

CASE MAY NOT BE UNCOMMON

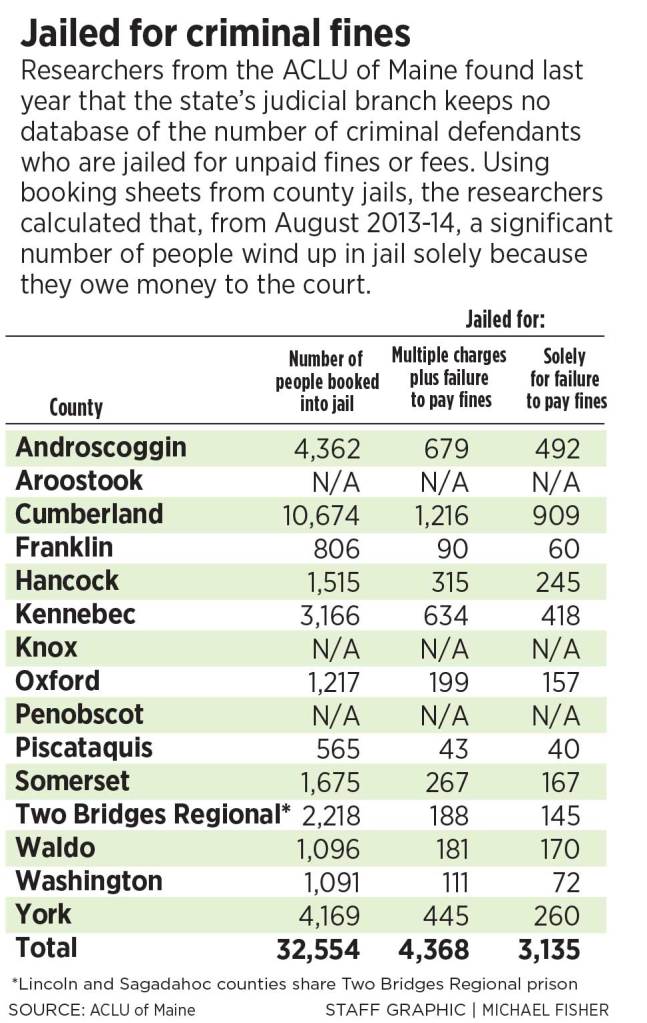

ACLU of Maine researchers who conducted the study said that Comeau’s case may not be uncommon. Nearly 10 percent of the inmates booked into the Cumberland County Jail between August 2013 and August 2014 were there solely on a warrant for failure to pay fines or restitution as ordered by the court. Of 10,674 booked during that period, 909 were arrested just for failing to pay court debts.

“I couldn’t pay. If they had given me a way to pay, I would have. Some people don’t care about going to jail, but I literally didn’t have the money,” said Comeau. He was released on Feb. 28, now lives with his mother in Portland and works two steady jobs.

At the Cumberland County Jail, Joyce found that during the last four months of 2014, 41 inmates were sentenced to pay off back fines or restitution. Thirteen of them actually served out their full time, while the remainder managed to come up with the money to pay off their debt or at least enough to start a new payment plan.

The total cost to taxpayers to jail the 13 individuals for a combined total of 232 days was $25,990 – to recoup $10,489 in fines or restitution.

The findings come as authorities across the country have begun examining whether the penalties for unpaid fines unfairly target the poor. In the wake of protests in Ferguson, Missouri, over the police shooting of an unarmed black man, civil liberties groups and federal officials found that city officials were charging high court fines and fees for nonviolent offenses such as traffic violations – and then arresting people when they didn’t pay. In some Missouri towns, the fines made up a significant portion of municipal revenue. In Alabama, the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a federal lawsuit in March against the city of Clanton and a private probation firm it had hired, claiming that the firm was threatening to send poor people to jail unless they paid outstanding tickets and court fines for minor crimes.

After defaulting on his restitution payment in July 2014, Comeau signed what he called “doomsday paperwork” at the Cumberland County Courthouse, promising that if he defaulted again, he would go to jail to pay off the debt.

He was arrested for shoplifting from Home Depot and was sentenced to 30 days in jail, which meant he couldn’t make his restitution payment in the graffiti case. He wrote a letter to the court on Oct. 21 to explain, but never got a hearing before a judge.

Comeau admits he’s to blame for his legal problems. He had been living on the streets of Portland and struggling with a drug problem and racked up about a half-dozen misdemeanor convictions for criminal mischief, assault, theft, criminal trespassing and drug possession.

Since his release, Comeau has stayed away from drugs and works two jobs at a construction company and a Portland food processing plant.

He still owes $1,200 in fines and another $695 in restitution, but is now able to keep up with his payments of $110 per month.

“Since it costs more money to hold me (in jail), I think it’s ridiculous,” he said. “I think you should be able to do community service. There has to be something better than $5 a day in jail. It’s definitely a horrible thing. I think their thought was if they put you in there for $5 a day, someone will come and bail you out. I couldn’t find a way to do it.”

TOO POOR TO PAY?

It is unclear how the ACLU of Maine’s findings on Maine jails compare to the number of inmates jailed for unpaid fines in other states or nationally. No federal agency compiles numbers on the nature of the violations that land people in jail.

“We don’t collect jail data nationally,” said Todd Minton, a statistician for the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics in Washington, D.C.

Lawmakers in Augusta have put off until next year any debate on a bill that would prohibit jailing people solely for failing to pay criminal fines. Under current state law, a judge can find defendants in contempt if they do not pay or fail to comply with a monthly payment plan. Judges can jail people who owe criminal fines; they receive $25 to $100 credit for each day they serve in jail. Those who owe restitution can pay it off only at a rate of $5 per day in jail, by statute.

Supporters of the bill, L.D. 951, liken the current system to a modern-day debtors’ prison that treats the poor more harshly than those who can afford to pay off their court debts. But opponents say fines, which can be paid on schedules as low as $10 per month, are an important part of criminal punishment and argue that no one who makes a good-faith effort is actually jailed. The Legislature’s Judiciary Committee voted last week to take up the bill again in January 2016.

Grainne Dunne, the ACLU of Maine staffer who led the study, said her team collected booking records from 12 of the state’s 15 jails and discovered the trend in Portland is mirrored in data collected statewide. Of the 32,554 jail bookings they counted from August 2013 to August 2014, they found 3,135 inmates were booked solely on warrants for failure to pay court fines or restitution.

Dunne said those numbers are considered estimates, since they were compiled by hand from each booking sheet.

“Getting information from the jails ended up being challenging, to say the least. It took a lot longer than we thought it would, and we still didn’t get complete information. We’re missing information from three jails: Penobscot, Aroostook and Knox,” Dunne said. “We found thousands of people that they booked just on failure to pay fines.”

Dunne said the ACLU of Maine requested booking records from Penobscot, Aroostook and Knox counties, but did not receive the information.

Oamshri Amarasingham, the public policy attorney for the ACLU of Maine, said that when a warrant is issued for someone’s arrest for failure to pay fines or restitution, the Bureau of Motor Vehicles immediately suspends the driver’s license and imposes another fee before it can be reinstated.

Amarasingham said the cycle that begins with incarceration leads to more serious life consequences, like losing transportation, driver’s licenses or jobs.

“If you can’t afford to pay your fine, at some point the amount is so big it’s a meaningless penalty. If you can’t afford to pay a $1,000 fine, it may as well be $100,000,” she said. “It’s crushing, crippling debt for so many people.”

Amarasingham said people can then become perpetual victims of the system.

“It doesn’t matter to me if I littered or was picked up on a minor drug offense. Now I have these exorbitant fines, and I have to pay all this money to get my license reinstated. Now it’s a barrier I am trying to overcome,” Amarasingham said.

Eric Gould, a 30-year-old Portland resident, has been in and out of jail for most of his adult life, primarily for marijuana-related offenses. He can’t remember a time when he wasn’t in over his head in debt from criminal fines.

Gould was jailed most recently for 64 days, earning credit for unpaid fines at a rate of $50 each day he was in jail, at a cost to taxpayers of $8,400 to recoup $3,200 in fines. That was on top of several months he’d already served in jail for unpaid restitution.

“I’ve pretty much only been out of jail six months out of the last 18,” he said.

Gould said that every time he is jailed, he loses whatever apartment or employment he has and any future ability to pay his debts.

“It costs me everything I have every single time, and they bitch at me, why can’t I pay more fines,” he said.

PROSECUTORS SAY POOR NOT TARGETED

Mary Ann Lynch, spokeswoman for the Judicial Branch, said that in every case in which someone has missed a court-ordered fine or restitution payment, the court first issues a letter telling the person he must appear before a judge.

“They are being arrested or having their probation revoked if they are willfully refusing to pay or if they have failed to appear in court. When we send them a letter saying you’ve missed your payment and when they fail to appear in court, we will issue a warrant,” Lynch said in testimony before lawmakers this month.

Lynch said that under current law, judges are often required to impose fines and fees regardless of a defendant’s ability to pay, but they have discretion on payment plans, she said.

She acknowledged, under questioning from lawmakers during a public hearing on L.D. 951, that homeless people or those without permanent addresses probably would not receive the court’s letter.

The ACLU of Maine study found that the judicial branch does not keep centralized or computerized data on people jailed for unpaid fines. It also found that most jail booking records from around the state do not reflect whether someone is homeless or transient.

Cumberland County District Attorney Stephanie Anderson said she’s in court nearly every day and doesn’t think the poor are being targeted.

“The mere notion of someone going to jail because they are poor brings up images of Dickens and ‘Bleak House.’ I don’t see that happening.” she said.

Anderson said judges’ hands are tied by minimum mandatory fines and fees set by the Legislature, especially in motor vehicle cases.

“I think the fines tend to be awfully high,” Anderson said. “We need to come up with a way where people can provide some sort of community restitution in lieu of fines.”

Anderson said she believes part of the problem is people with mental illness, disabilities and other debilitating problems who are left untreated in the community.

When the state closed Pineland Hospital and Training Center in New Gloucester in 1996 after gradually moving residents for years into apartments without caretakers, Anderson said she knew that many of the residents would wind up in jail.

Anderson said a law prohibiting jailing people for unpaid fines won’t solve the problem.

“Let’s get honest about what’s going on,” Anderson said. “The root of all this is mental illness or alcoholism, substance abuse and addiction.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story