Citizen groups that oppose large-scale wind power development in Maine reacted strongly Tuesday to news that developers were proposing numerous wind farms in the state that would supply clean energy to southern New England. The groups have been fighting several of the projects individually, but were alarmed at the overall scale of the combined proposals.

“This will turn Maine into a wind plantation,” said Chris O’Neil, a spokesman for Friends of Maine’s Mountains.

Maine figured prominently this week in a multibillion-dollar competition to provide power to Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts, with companies submitting bids to build giant wind farms in Aroostook County and the western mountains. Together the projects would more than triple the state’s turbine capacity, but the power would not be sold in Maine.

O’Neil said southern New England states were shuttering nuclear, oil and coal plants in their quest for cleaner power, but not taking responsibility for replacing the lost generation.

“They’re jumping off a cliff and expecting Maine to bail them out,” he said.

But energy officials and industry representatives in Maine were tamping down impressions that all or even most of these projects would be built.

“I’ve been trying to get the public prepared for this and not think that all of these projects will be developed,” said Patrick Woodcock, Gov. Paul LePage’s energy director. “In fact, under the request-for-proposals, it’s not even possible for all of them to be chosen.”

PROJECT LIST INCLUDES POWER LINES

Woodcock was reacting to the release Monday of the names of 51 separate projects throughout the region from 23 different development groups that responded to a joint request from Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island. The three states last year asked for proposals for clean energy generation that would contribute roughly 600 megawatts of new capacity to southern New England. That’s nearly the output of the Pilgrim nuclear plant in Plymouth, Massachusetts, which serves a half-million homes and is set to close in 2019. The states are trying to diversify their energy supply, cut emissions associated with climate change and lower energy costs for residents.

The project list includes a wide range of wind, hydroelectric and solar projects in New England and Canada, as well as transmission lines to link them to the regional grid.

Proposals in Maine include bids to unlock a large reserve of wind power potential in Aroostook County, which lacks a transmission connection to the rest of New England. One plan from SunEdison is a massive, 600-megawatt wind farm called King Pine. Another involves two projects from EDP Renewables, Number Nine Wind Farm and Horse Mountain, that together would add up to 650 megawatts.

These projects could get to market via a new transmission line that would jointly be built by Central Maine Power and Emera Maine, called the Maine Renewable Energy Interconnect. It would require 150 miles of new wires and new substations.

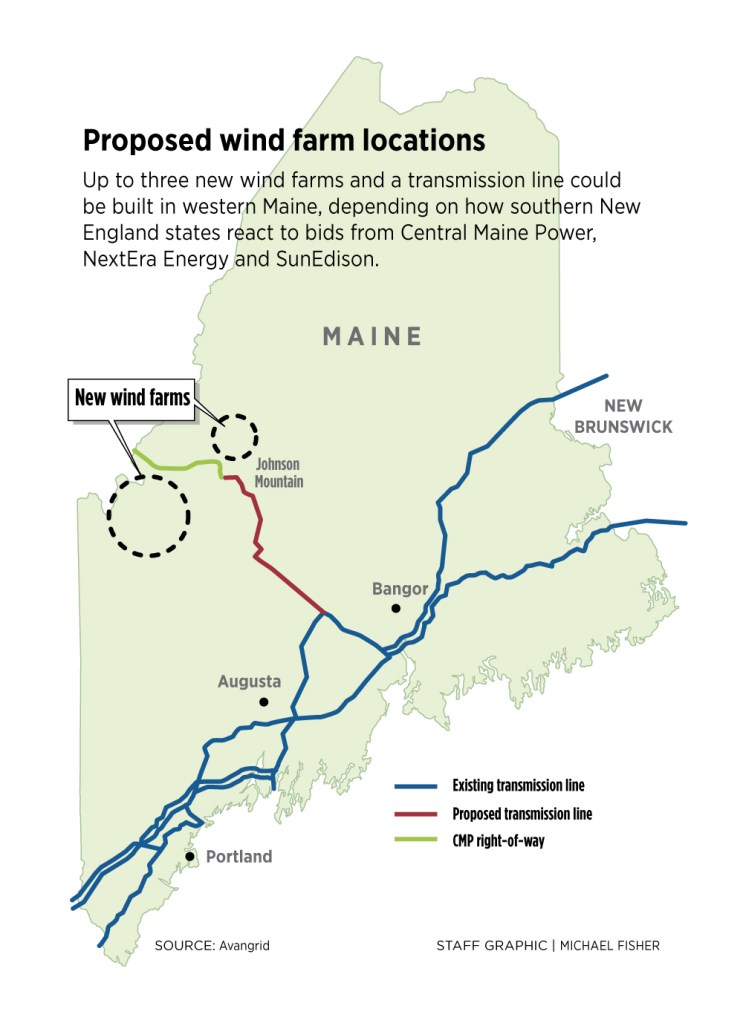

In the western mountains, NextEra Energy is proposing two wind farms near Eustis that total 461 megawatts. Near Moosehead Lake, SunEdison has proposed an 85-megawatt farm called Somerset Wind.

Those wind farms would be connected to the grid by a 66-mile transmission line built by CMP, called the Maine Clean Power Connection.

Another SunEdison project called Weaver Wind could have a capacity of 72 megawatts in Hancock County. EverPower wants to build a 250-megawatt wind farm in Washington County, near Cherryfield.

Also on the list are a couple of solar-electric projects, in Sanford and Farmington, from Ranger Solar. They add up to 130 megawatts.

PROS, CONS OF POWER EVOLUTION

Richard McDonald, president of the Saving Maine anti-wind group, said the regional clean energy plan is happening at a time when Maine already is facing a stepped-up pace of new wind projects. A bill currently in the Legislature would allow CMP and Emera to get back in the generation business, which he said would mean more wind farms.

McDonald also drew a connection between the recent appointment of former Gov. John Baldacci as vice chairman of Avangrid, the new parent company of CMP. Baldacci was instrumental in supporting a law that paved the way for wind power development in 2008.

“It’s the same old ballgame we had in 2008,” McDonald said. “The political landscape in Maine is teed up to make this happen. And it’s going to permanently change the character of western and northern Maine.”

But John Carroll, a spokesman for Avangrid, said the projects reflect an evolution of Maine’s energy resources. The existing transmission system was laid out in the 1960s to connect areas where nuclear and fossil fuel plants were built. New technology has made it possible to tap wind power for the region, he said, so transmission is being extended to areas with the greatest potential.

Key details of each bid proposal, including the cost of the projects and price of the electricity, are confidential for competitive reasons. Utilities and state officials now will begin a process of culling through the details. They are due to make selections in July.

Rate impact seems to be the top consideration, Woodcock said, because the full cost of developing the projects and building the transmission lines will be borne by southern New England electric customers. It’s less clear, he said, whether potential delays caused by local opposition would be a factor in choosing proposals.

“At this stage,” he said, “the states are going to look at pricing. But it’s hard for the evaluation teams to know what’s likely to get a permit.”

The Maine projects are competing with some heavy hitters in the energy field.

They include a plan called “The Wind and Energy Response,” which is a 400-megawatt wind farm in New York state from Invenergy Wind LLC, supplemented with Canadian water power from Hydro-Quebec. The combination would produce clean energy all day, not just when the wind blows, the developers say. Power would move through the Vermont Green Line, a transmission project running under Lake Champlain.

Also on the table is Northern Pass, a 192-mile transmission line that will bring 1,090 megawatts of energy from Hydro-Quebec through New Hampshire. That project has faced opposition for running through the White Mountain National Forest, but developers have since redesigned it to bury the cable underground.

MAINE MAY TRY TO SWAY PROCESS

These competing projects highlight the fact that southern New England also is going to be looking for a diversity of generation that, unlike wind, can run at predictable times, said Jeremy Payne, executive director of the Maine Renewable Energy Association. That’s why being able to get public support and regulatory permits for the transmission lines is just as important as the actual generators, he said.

“What makes this request-for-proposals unique is that transmission is part of the discussion for the first time,” he said. “That’s been a missing component.”

Woodcock said he considered Northern Pass and the other major projects to be “serious proposals” that compete with those contemplated in Maine. He said his office would decide at some point whether to offer an opinion that might help guide the decision-making process in southern New England.

“We continue to evaluate the proposals,” he said. ” The state may provide comments to Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island on what development would be in the best interest of the state of Maine.”

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.