Two of the winter’s most interesting local exhibitions have been collaborations involving the art faculties of the University of Southern Maine and the University of New England. They are very different kinds of shows, however.

The USM show, “Forging Affinities,” connects art faculty with members of the Union of Maine Visual Artists. The resulting work is what you would expectedly get when community-oriented professionals work with each other: highly finished, crisply clear and even elegant works that comprise one of the best looking shows I have ever seen in the handsome Gorham gallery.

“Wonder” at UNE combines professional artists with non-art faculty. It is a strange show that operates outside of expectations. While the USM show hits a uniformly high standard, the UNE show is all over the place and, because of that, it is far more challenging, though no less enjoyable.

At USM, lecturer and artist Lin Lisberger joined with UMVA member and painter Grace DeGennaro to make a pair of collaborative prints. While Lisberger is best known for her carved wooden sculptures, her large loose works on paper exude a bold, confident and jaunty sensibility. DeGennaro’s best works, on the other hand, are about systems that bridge the rational world with the irrational power of the spiritual imagination.

What is striking about the collaborative prints is that they fit these descriptions to a T – while feeling nothing like the work of either artist. One print features a flat, stylized tree form (Lisberger) floating above a simple triangle (DeGennaro); but as it plays the role of a biblical hill, the triangle fleshes out and becomes (poof!) a pyramid – a symbol rife with metaphysics and mystery.

The most engaging work is “Inside/Out,” a small room dedicated to an experientially wild installation by USM faculty Michael Shaughnessy and Geoffrey Leighton with UMVA members Nora Tryon and Anita Clearfield (both of whom I have served with on the editorial board of the Maine Arts Journal: The UMVA Quarterly). It combines theatrical curtains with found objects, mirrors and video projections that reach (rather literally) both through the floor and into the ceiling.

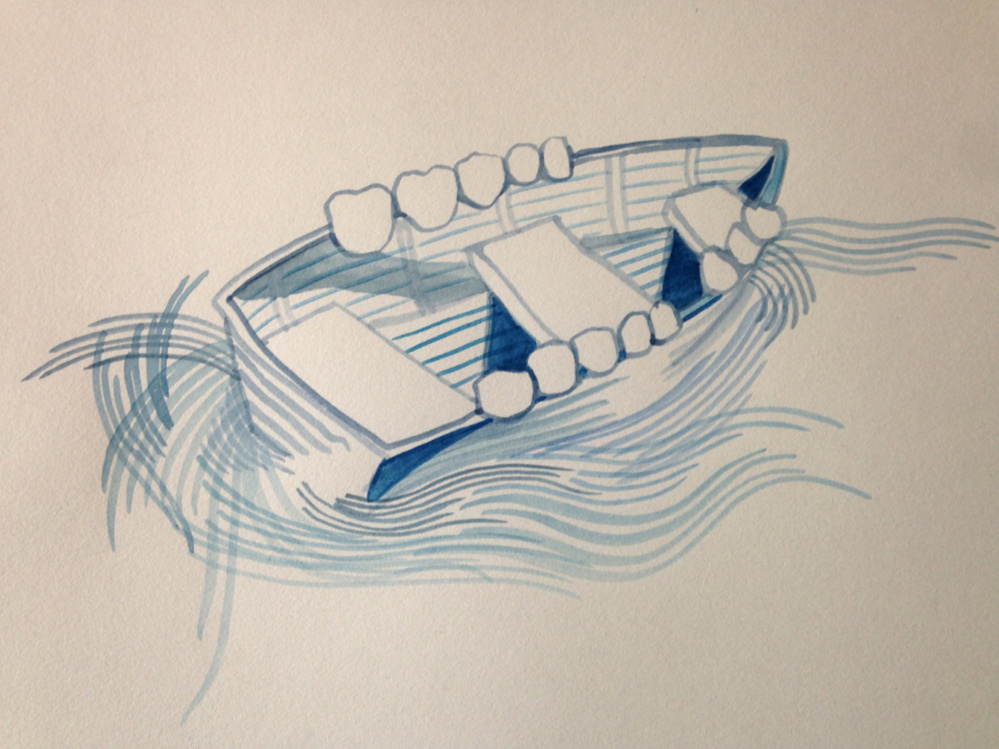

At UNE’s “Wonder,” the results are – predictably – less predictable. Alex Rheault’s wall of drawings, for example, is paired with a multimedia video about the extent to which anxiety about visiting dentists has a huge impact on the overall dental health of Americans. Rheault’s drawings first appear as witty and playful machinations about mouths and (maybe Freudian?) teeth anxieties. But as the theme comes into focus, the drawings appear more and more as illustrations of an issue that is a bona fide concern.

The most intriguing work in that show is “Success” by Michael Vickery, a terrarium in which a tiny and well-manicured house complete with pink flamingos and an American flag gets overgrown (and then overwhelmed) by the grasses and plants that had once made it appear so beautifully manicured. It’s an obvious but successful metaphor accompanied by a commentary by social work professor Lori Power that succeeds in psychologizing the effect, rather than leaving it to swell as a lesson in environmental self-righteousness.

The collaboration that best punctuates the professional practices underlying such a show is a book, “Carnivorous Plants: A Compendium of Most Unusual Species,” with etchings by artist Stephen Burt and text by environmental studies professor Pamela Morgan. Not only is the folded folio a fascinating and gorgeous thing, but Burt and Morgan present draft drawings and a playful illustration painted directly on the gallery wall by Burt. (The “mousetrap” is particularly amazing.)

My 11-year-old son was at first disturbed by Holly Haywood’s extraordinary photographs of “Ana,” a young woman undergoing extremely invasive treatments for epilepsy and a serious shoulder problem. While the ensuing conversation with my son about the piece may have been the most important part of our visit, it was extremely difficult.

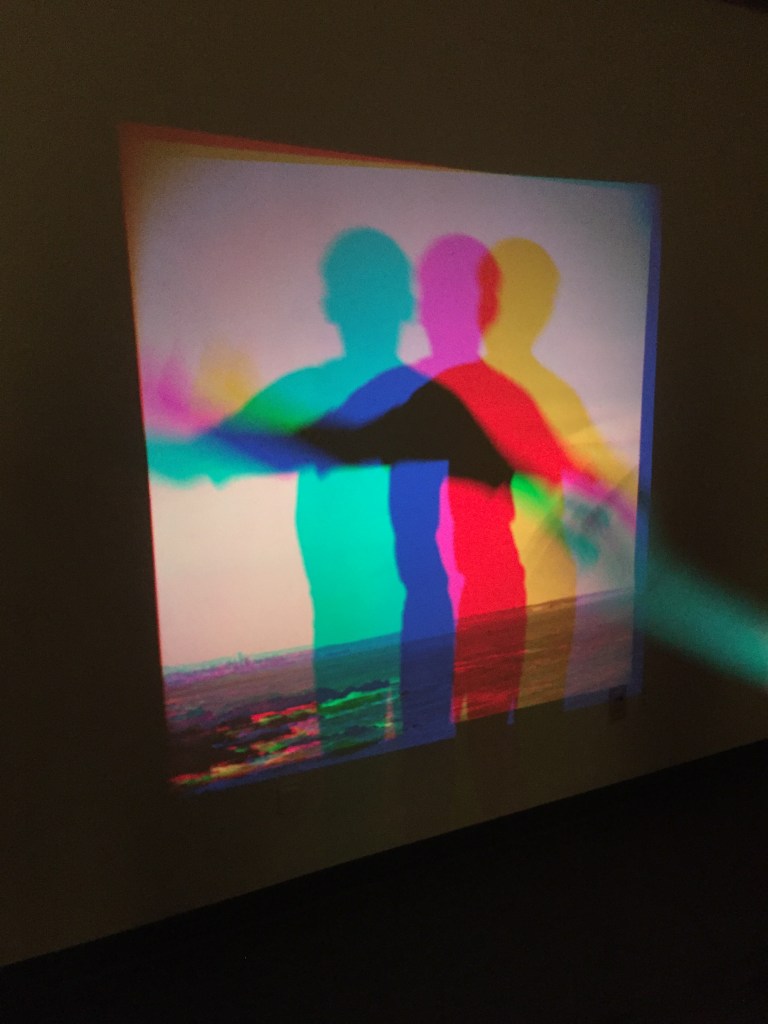

Yet I wanted to bring my son because I knew he would (and did) enjoy two of the interactive installations. Jennifer Baugh’s “Compassionate Tough” carved linoleum block panels and the prints she made from them are all UV-reactive, so exploring them with the accompanying UV flashlights is fun for kids of any age. The other is Luc Demers’ color-filtered three-projector images in the darkened lower gallery. My son and a friend loved it: They engaged with both the theatricality of the space and the technical aspects of the photography. A single scene was photographed with different color filters. The three images are projected simultaneously from three projectors – each with a red, green or blue filter in front of it. (This is a reprisal of a project Demers did for an excellent “artist intervention” at the Portland Museum of Art.) With the boys, the conversation turned into a highly interactive lesson about the differences between additive and subtractive colors (i.e., with lights, red plus green makes yellow; with pigments, they make brown).

To be frank, collaboration exhibitions can be less than exciting. They are so often dry and contrived. But when artists challenge each other or riff off each other, collaborations can be fascinating. Through their cubist paintings, for example, Picasso and Braque pushed each other past where conversations could have taken them – and their collaborative movement changed art forever. Without collaboration in jazz, there is no communal groove. The Surrealist game of exquisite corpse pits artists to compete and surprise each other, and so on.

When creative minds challenge and push each other, genuinely new things can happen. New for the sake of new rarely trumps the refinement of what is already good, but it offers the possibility of excitement. And when you’re looking for the road less traveled, new ones are the least traveled of any.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story