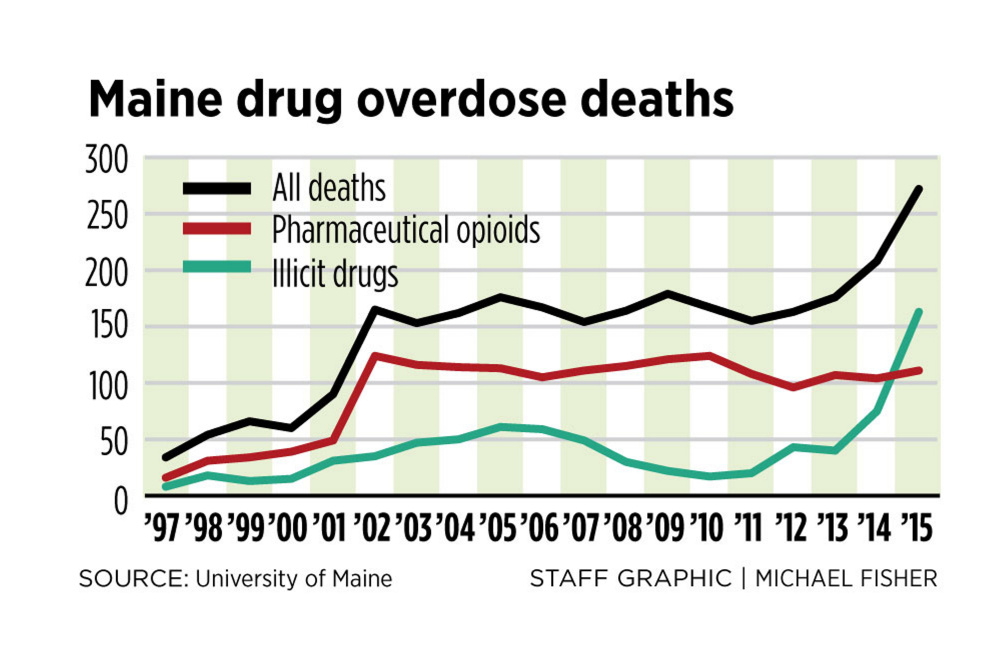

Drug overdose deaths in Maine soared by 31 percent in 2015, reaching a new high of 272 fatalities that was fueled by a near doubling of heroin deaths, according to data released Monday by the Attorney General’s Office.

“When I hear these numbers, they are so sobering,” said Cynthia Fielders of Eliot, whose son, Michael Fielders, 31, died of a heroin overdose Nov. 3. “But if we sit back and do nothing, and put our blinders on, these numbers will continue to double or triple.”

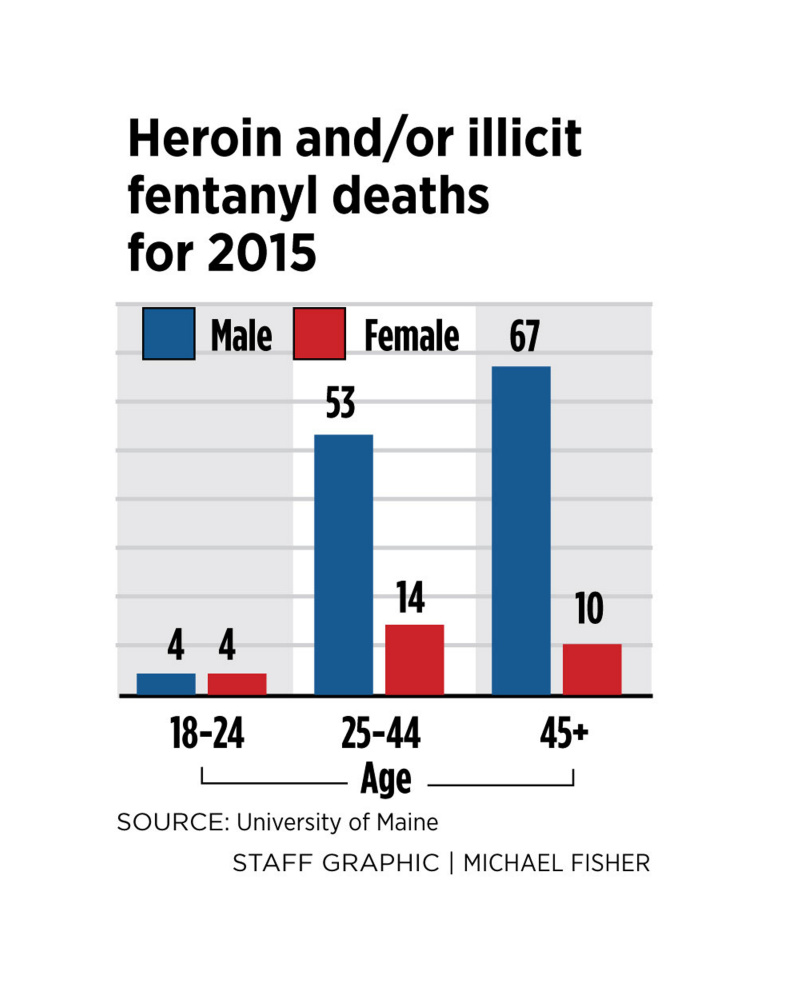

There were 107 deaths from heroin and a total of 157 deaths from heroin, fentanyl, acetyl fentanyl or some combination. Fentanyl is often used as a heroin substitute, and some who purchase street drugs believe they are buying heroin when they are actually getting fentanyl or heroin laced with fentanyl.

Fifty-seven people died of heroin overdoses in 2014, when 208 deaths were caused by drug overdoses.

The vast majority of the 272 deaths in 2015 were caused by heroin, fentanyl or prescription opioids, according to the Attorney General’s Office. Most overdose deaths involve two or more drugs, meaning one overdose could show up in multiple categories.

The number of fatal drug overdoses has climbed steadily since 2011, when the state had 155.

“These figures are shocking,” Attorney General Janet Mills said in a written statement. “Maine averaged more than five drug deaths per week. That is five families every week losing a loved one to drugs.”

Fielders said her family and friends are starting a nonprofit called “Out of the Shadows” that will advocate for better access to treatment in Maine and also work to reduce the stigma often associated with heroin abuse.

Fielders said her son first became addicted to painkillers after hurting his back in 2009 and being prescribed Percocet. Four out of five new heroin users are first addicted to prescription opioids, according to the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

Marcella Sorg, a research associate professor at the University of Maine’s anthropology department, which compiled the statistics for the Attorney General’s Office, said the trend lines over the past several years clearly show many people move from prescription addiction to heroin.

“We have had fairly constant levels of prescription opioid deaths. But the deaths by illicit drugs has spiked,” Sorg said. “People become addicted to prescription opioids, their pill supply dries up and they start using heroin. The brain craves the opioids and reacts similarly, whether it’s prescription opioids or heroin.”

Fielders said the problem is widespread in middle-class suburbs and wealthy enclaves and isn’t limited to homeless or poor people. The average age of the people who overdosed was 42, up slightly from 2014.

“We’ve got to do more,” Fielders said. “We’ve got to do more as a community, and we’ve got to come together.” She and her husband are raising their deceased son’s two children.

Prescription painkillers accounted for 111 deaths in 2015, and the LePage administration last week proposed a bill that would further tighten rules on opioid prescriptions, making it less likely that patients could go “doctor shopping” or receive long-term prescriptions for opioids.

It’s one of a number of bills pending in the Legislature that aim to alleviate the state’s opioid problem.

About 15,500 Mainers received opioid addiction treatment in 2015, according to data released Monday by the Maine Department of Health and Human Services.

But public health experts say Maine’s treatment options are sparse, and in 2015 the options decreased further because two treatment centers, Mercy Recovery Center in Westbrook and Spectrum Health Systems in Sanford, closed.

Maine’s low reimbursement rates and defeat of Medicaid expansion have made it financially difficult for treatment centers to offer broad access to patients, experts say.

Republican Sen. Thomas Saviello of Wilton has introduced a bill that would expand Medicaid, and has said one of the major selling points is that expansion would substantially increase access to substance abuse treatment. The administration of Gov. Paul LePage remains staunchly opposed to Medicaid expansion, so Saviello’s bill would need to muster two-thirds support in the Legislature to override a LePage veto.

Substance abuse counselors say heroin addicts are much more likely to lack insurance than the general population, and without a way to pay for treatment, often lack the resources to get into a treatment program. Many of the uninsured would qualify for Medicaid if it were expanded.

Dr. Mary Dowd, a physician who works at the Milestone Foundation, which operates a detox center in Portland and a long-term rehabilitation center in Old Orchard Beach, said few of the people she sees are getting into treatment programs.

“This doesn’t surprise me at all,” Dowd said. “I’m seeing new addicts all the time, every week, coming to Milestone, and many times we can’t get them into treatment.”

Cumberland County had 86 overdose deaths, the most for any county and 32 percent of the number statewide. Of those overdose deaths, 46 occurred in Portland, 17 percent of the total and the most in any city.

“We have to turn this around,” said Portland Police Chief Michael Sauschuck. “I’m certainly saddened by the numbers, but not surprised. We’re on the front lines of this every day.”

Sauschuck said a prevention-and-intervention program that the city started in January, called Law Enforcement Addiction Advocacy Program, is working to connect drug users with treatment, housing and other resources. But Sauschuck said the program is not a “silver bullet” and more needs to be done.

Sauschuck said the LEAAP program, like many that try to help addicts, is hampered by the state’s lack of treatment options.

“It’s time for an investment,” he said. “What we need to do is to focus on systemwide changes.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story