Maine’s obsolete biomass power plants and its struggling or shuttered paper mills are world-class assets that can become testing grounds for a new manufacturing economy based on sustainably harvested wood, says an international group of energy developers.

Seen through fresh eyes, these industrial relics are the pieces with which entrepreneurs can build bioenergy parks, where all parts of a tree are used to make electricity, fuel, food, material and other things, eventually replacing similar products made from petroleum.

This vision is in the early stages, and it’s too soon to know if organizers can assemble the mix of money, applied technology and business outreach needed to create such a grand transformation. But there are reasons for cautious optimism: Investment in Maine is being sought, and similar projects have gained ground in Europe.

Members of the development group, under the name Stored Solar J&WE, took the first step last fall by buying two idled wood-fired plants in West Enfield and Jonesboro. The plants are back online, restoring jobs for 84 employees and 200 or so loggers and truckers. The restart was made possible through a share of a $13.4 million subsidy that Maine lawmakers approved last year, a lifeline to keep the state’s wood-fed biomass power industry alive for up to two years.

The 31-year-old plants bought by Stored Solar are inefficient and can’t be profitable without above-market power contracts from other states. So the clock is ticking for Stored Solar to find other businesses that can locate next to the plants and use the now-wasted heat that goes up the smokestack. Having manufacturers use that heat would provide a new source of revenue and make the plants more valuable in power markets.

“A lot of people complain it’s too expensive to do business in Maine,” said Kimberly Samaha, chief expansion officer at Synthesis Venture Fund Partners, which has a business relationship with Stored Solar. “This is about proving a new economic model.”

Investors and developers are being sought for Maine’s first bioenergy park through an unusual process called the Maine Born Global Challenge. It’s marketing Maine the way a real estate developer might praise the potential of a city’s broken-down neighborhoods. Here’s an example from the online presentation:

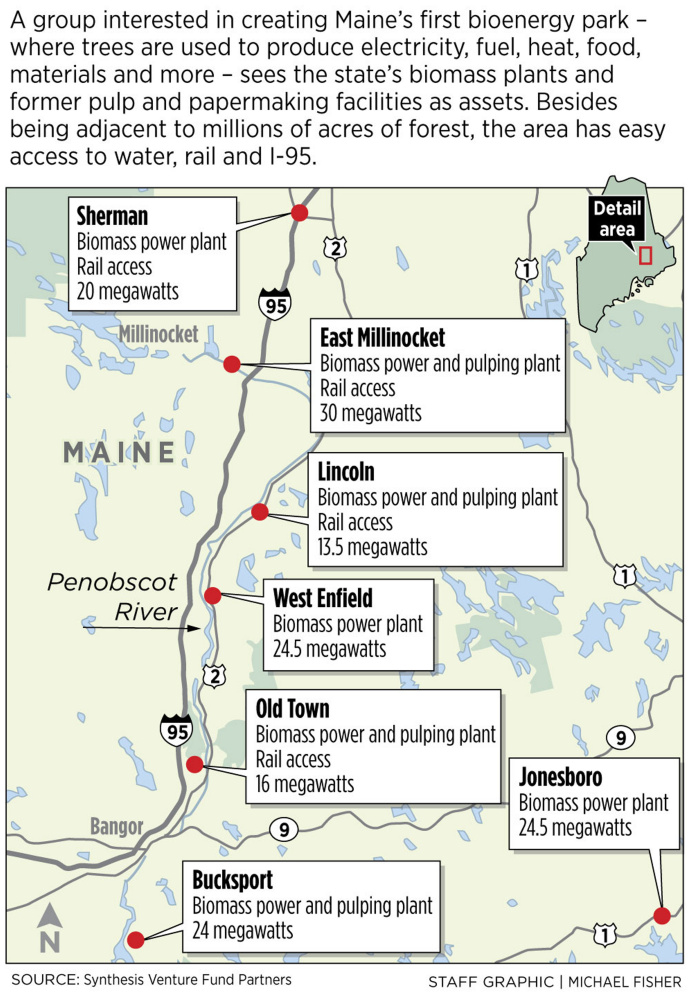

“Maine’s existing bioenergy and closed paper and pulp facilities sit on hundreds of acres of land, have abundant access to water, as many sit on the Penobscot River, have access to rail, ports and federal interstate highways. All of these sites have biomass-energy plants in varying operational conditions. Many of the paper and pulp facilities have been sold for scrap metal in bankruptcy filings, but have maintained the power plant and some of the surrounding buildings, which can still be repurposed.”

A POTENTIAL GAME-CHANGER

Samaha said she has been contacted by ventures that want to use harvested trees to make fuel and use the sugars in wood pulp to create other products. Others want to capture waste heat from the biomass plants to warm greenhouses for growing plants or raising fish.

Applicants that have the ability to move ahead will be selected over the next month and announced March 1 at a bioeconomy conference in Washington, D.C., she said. Picking specific project sites and seeking financing and approvals would follow.

“It’s about trying to see how we can make energy parks out of these simple biomass plants,” Samaha said. “It’s the intersection between food and energy – a closed loop in which waste streams from one process are feedstock for another.”

Biorefineries are becoming a reality in other countries. But such an accomplishment would be a game-changer in rural Maine, where abandoned or struggling paper mills and wood-fired power plants stretch from Fort Fairfield to Bucksport, and from Stratton to Jonesboro. Six paper mills have closed in the past three years, removing thousands of jobs and an estimated $1.3 billion from the state’s economy.

In this bleak atmosphere, Stored Solar offers a glimpse of light. But there are unanswered questions about the company and its plans.

Stored Solar is owned by a French corporation named Capergy. The company is described as an asset management and energy development firm whose chairman and chief executive is Fahim Samaha, the husband of Kimberly Samaha.

The couple told a gathering at a forest industry conference last fall that they used their own money to buy the two biomass plants. The sale price is confidential, according to the Maine Public Utilities Commission, which approved the power contracts for the plants.

Stored Solar also asked the state to apply for a multimillion-dollar loan guarantee with the federal Department of Energy. This program is meant to support new renewable energy technologies not yet in commercial use. The state declined to do so, according to a source with knowledge of the talks, and the company went ahead on its own. It’s unclear how the Department of Energy program will operate under the Trump administration.

The structure of Synthesis Venture Fund Partners also is unconventional. It appears to be made up of 20 or so people described on its website as an international “team of developers, financiers, policy advisers and entrepreneurs” who work together to bring innovative energy projects to a commercial stage. They meet regularly in Bordeaux, France.

Kimberly Samaha didn’t respond to questions about the structure of the companies and their financial or ownership arrangements.

CLUSTER OF FOREST OPERATIONS

According to the presentation for the Maine Born Global Challenge, the biomass plants in West Enfield and Jonesboro and a shuttered paper mill in East Millinocket could be turned into energy parks. The location of these and other forest products operations, particularly the cluster along the Penobscot River, can benefit from their proximity.

Despite unanswered questions, the Stored Solar purchase is one of the few cases where forest-sector investors are coming to Maine instead of leaving, so it can’t help but generate cautious optimism.

“I would say that in the industry, Stored Solar is viewed with some level of hopeful skepticism,” said Eric Kingsley, a Portland-based forest products consultant and vice president of Innovative Natural Resource Solutions. “I so want them to be successful. But that doesn’t make the cold analyst in me gloss over everything else.”

While the challenges are formidable, Kingsley said, Stored Solar has arrived at an opportune time.

Maine’s vast network of private logging roads remain intact, linking the largest, contiguous, privately owned working forest in the United States. Mill closures have created a surplus of timber, especially softwood, that can be sustainably harvested for other uses.

At the same time, a legislative study commission presented recommendations to lawmakers this winter on how to help revive biomass power and, in turn, the forest products industry. Some proposals, such as creating financial incentives for thermal energy, could benefit Stored Solar and other businesses.

Assistance also is coming from the federal government in the form of an Economic Development Assessment Team, requested by U.S. Sens. Susan Collins and Angus King to help revive forest products. Last month, the University of Maine and a federal energy lab agreed to work together on developing biomaterials from the forest.

“Maine has a lot to build on,” Kingsley said.

The restart of the two wood-fired power plants already is having a tangible impact.

WELCOMING THE OPPORTUNITY

Brian Souers, president of Treeline Inc. in Lincoln, has a dozen workers who help supply 250,000 tons a year of low-grade trees, sawdust and bark to West Enfield. He’s hopeful that the new owner can follow through on its larger plans.

“This is the best opportunity we can hope for to make those biomass plants viable,” said Souers, a past president of the Professional Logging Contractors of Maine. “This kind of effort is what they need and no one has been willing to do it.”

The developers also have been meeting with state officials, including Rosaire Pelletier, the forest products liaison for the Department of Economic and Community Development. Pelletier declined to discuss the nature of those talks, but praised Stored Solar for restarting the biomass plants and pursuing its ambitious plans.

“We need to take our blinders off and move on,” he said. “Whoever is willing to invest in the forest products industry and take the risks, I am in favor of.”

Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@pressherald.com

Twitter: TuxTurkel

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story