WALDOBORO — Alexis Zimba-Kirby has just walked a half-dozen middle schoolers through making a simple beet salad.

Lessons were learned on both sides. One, shallots are like onions, but not as spicy. Two, beets are a source of sugar. And three, when trying to get kids to try something new, patience is key.

Summer Wasilowski, 12, has tried couscous, ground cherries and squash during her time in the school’s Outsiders Club – she’s even started making couscous at home – but she eyed the cilantro in the beet salad with skepticism, and when she forced herself to taste it, she looked as if her BFF had just dumped her.

“It kind of tastes like pool water,” she said.

Nevertheless, Wasilowski said she might try cilantro again sometime, “if I have something to drink after it.”

Small victories. That’s what Zimba-Kirby lives for in her job as a FoodCorps service member in Maine. Her mission is to connect kids to healthier foods through cooking, tasting, gardening, nutrition education and developing a school culture that values healthy food choices. That means getting the students at Medomak Middle School, where pizza and chicken burgers are the top-selling lunches, to try a bite of beet salad.

“I’m always amazed at how picky our kids are,” Zimba-Kirby said. “So many of these kids will only eat two or three things. So any time a kid will try something, even if they don’t like it, for me that’s a win.”

A FORCE FOR FOOD

FoodCorps is a national service organization affiliated with AmeriCorps that places its service members in high-need areas where schools are an important part of the nutritional safety net.

Including Zimba-Kirby, a dozen FoodCorps members are stationed in Maine this school year, working with schoolchildren and with school food service staff to make food more appetizing and healthy.

This month, the FoodCorps foot soldiers in Maine are:

• Holding cooking classes at two Portland elementary schools.

• Preparing a lunchroom hummus taste test at Lewiston High School, with an eye toward adding the spread to the school lunch menu.

• Preparing a free community dinner at Troy Central School to open up a conversation about food and health.

• Leading fifth-grade “Sprout Scouts” at the Albert S. Hall School in Waterville in planning the school garden and designing seed packets.

• Taking a field trip to Aldermere Farm in Rockport to see the Belted Galloway cattle.

The activities are all small steps toward a long-term goal. As Cecily Upton, a co-founder of FoodCorps and a resident of South Portland, put it, “We came into being as a health organization trying to address kids’ connection to healthy food and hoping that by establishing really good habits early, they would be less likely to have that link to disease and have a longer, more productive life.”

So far, the program appears to be on track. It’s still too early to evaluate its impact on long-term health problems such as obesity and diabetes, so the organization measures its success by examining the consumption of healthy foods. Results just in from an external evaluation done by researchers at Columbia University, Upton said, show that at 20 FoodCorps schools around the country – Portland’s Riverton School among them – children are eating three times more healthy foods during school lunch than they did before FoodCorps entered the picture.

MARSHALLING THE TROOPS

FoodCorps got its start in 2010 – Maine was a founding state. It grew out of a discussion at a Kellogg Foundation conference in California. Upton, who was there and now works in FoodCorps as vice president of innovation and strategic partnerships, remembers it this way: When the opportunity came up to discuss new ideas, another conference attendee, Curt Ellis, raised the idea of using public service organizations such as AmeriCorps to address some of the gaps he saw in food and health systems. Ellis now serves as chief executive officer of FoodCorps.

About a half-dozen people from the conference ultimately committed to getting something started.

“The idea was that we had seen tremendous amounts of enthusiasm from college-age people in our own spheres of work who were eager and excited to do work in food,” Upton said. “They had been exposed to new ideas around food systems and food justice at their college or university, and they were graduating and didn’t see a lot of opportunity to pursue that professionally.

“And then there were quite a number of projects happening in schools trying to get kids reconnected to where food comes from, how to grow it, how to cook it, how to enjoy it, really exposing them to those basics,” she continued. “Parents, community members, volunteers were excited about it, but couldn’t necessarily sustain it, and the schools couldn’t sustain it on their own, so there was a real human resource gap there.”

The group secured initial funding from AmeriCorps and the Kellogg Foundation, and spent the next 18 months planning.

During FoodCorps’ first year, the 2010-2011 school year, 50 service members were sent to 10 states, including six to Maine. This year, 215 service members are working in 18 states. There are no immediate plans to expand to other states, Upton said. But FoodCorps would like to invest more heavily in the states that already have programs and to double the number of its service members over the next few years.

FoodCorps attracts lots of young people who are eager to establish a career in food. The organization’s members and staff like to joke that nabbing a spot is as competitive as getting into Harvard. As many as 1,000 people apply for those 215 service member positions.

Zimba-Kirby thinks one reason is that “the time is right for food and social justice. All those things are kind of hip.” Also, she added, “it’s still really hard to graduate with any kind of humanities degree and get a job.”

Though FoodCorps is open to people of all ages, from high school graduates to grandparents, scan the photos on the organization’s website, and it’s clear that the majority are fresh-faced young adults. Many have college or culinary arts degrees, Upton says. More than half serve in their home states. They get an annual stipend of $17,500, plus a $5,815 education award that can be used to either pay off student loans or fund further education. (FoodCorps fundraises to cover 70 percent of the program costs. Another 20 percent comes from federal AmeriCorps grants, and the remaining 10 percent is provided by the service areas, which pay $6,250 each to host a FoodCorps member.)

After a week of intensive training, service members are sent into the community. While FoodCorps members are granted a lot of freedom to develop programs, they’re also handed tools that the organizations knows will work – things like taste testing and a “Harvest of the Month,” two programs that introduces a new fruit or vegetable to children each month.

FoodCorps instruction is coordinated with classroom lessons, Upton said, “so it’s really integrated into what the students are learning, and it feels like a real benefit to the teacher and not an add-on that they have to take time out of their day for.”

If a math class is working on fractions, for example, the FoodCorps member might drop in to talk about measuring ingredients for recipes. If a science class is learning the parts of a plant, school garden work will take that into account. Students studying history and culture might plant heritage seeds in a pioneer garden.

Members must spend 1,700 hours total in up to three schools over the course of the year, said Vina Lindley of the University of Maine Cooperative Extension, who manages the state’s FoodCorps program. “A lot of them go above and beyond that, really,” she added.

At the Albert S. Hall School in Waterville, service member Sam McClean is helping the kids plan a school garden this month, as well as organizing a taste test of a spelt grain salad. “We would not be able to do what we’re doing without FoodCorps,” Hall school teacher Mary Dunn said.

FOOD + KIDS = FULFILLMENT

Shana Wallace, a 23-year-old service member based in Lewiston, moved to Maine from New York to attend Bates College. Before signing up for FoodCorps, she had already helped manage a farmers market, worked in commercial kitchens and on a farm. She says she joined FoodCorps because she wanted to marry her love of food with her love of children.

Wallace works with mostly immigrant children who come from backgrounds where food is associated with survival.

“Many of my students come from very food-anxious environments,” she said. “They don’t associate food or growing food or eating with any sort of joy or excitement.” She tries to change that, hoping to instill in them the importance of trying new things, and the value of enjoying food.

This is her last year with FoodCorps, which limits members to two-year terms. Through FoodCorps, Wallace said she has “really fallen in love with working with children and teens.”

There’s the girl who doesn’t like to eat onions but has grown so confident chopping them in cooking classes she refuses to let anyone else do it because “it’s her job now.” And then there’s watching the children who have never cut a banana before and think it’s fun.

“I’ve seen so much growth in so many of these children,” Wallace said. “It’s been such a joy to work with them. I think this is the community I want to work with for the rest of my life.”

A VEGGIE FREE-FOR-ALL

By her own admission, Alexis Zimba-Kirby used to “hate kids.” Now she is realizing that she loves to teach.

In Waldoboro, where she teaches students of all ages (though primarily elementary and middle schoolers), her days are flexible and varied. She works with the health teacher when the lesson is nutrition, and with the science teacher when the class is studying soils. When she landed a grant to pay for a hoop house for the school garden, Zimba-Kirby discussed erecting it with the principal, the maintenance staff and the school board. Lately, she has been reviewing the results of a survey she designed and implemented on school lunch with the superintendent and the district’s nutrition director.

An Iowa native, Zimba-Kirby minored in food studies at New York University and is now studying for an online master’s in sustainable food systems. After college, she cooked for a time at the former Saltwater Farm restaurant in Rockport, where the kitchen’s local sourcing fueled her interest in becoming a farmer. She hopes her FoodCorps experience will make her more attractive to employers; she’d like to continue to work in food systems while she and her fiancé save up to buy a farm.

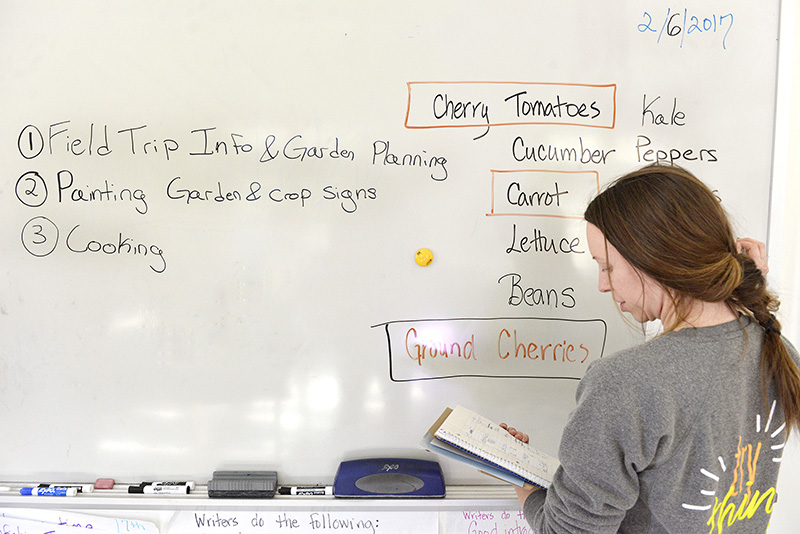

At a recent meeting of the Outsiders Club at Medomak Middle School, a half-dozen students painted signs for the school’s garden while they planned what to plant. Zimba-Kirby, wearing a FoodCorps T-shirt with a bunch of carrots on the front and the words “Try Things” in bright orange and yellow on the back, scribbled crops on a white board.

“OK, let’s figure this out,” she said. “Potatoes – do we want potatoes?”

“Yes, potatoes!” exclaimed 12-year-old Dante Paton, a seventh-grader who fell in love with the “sweet and delicious” ground cherries the club planted last year.

Eventually, the list grew to include radishes, kale, spinach, peppers, winter squash, ground cherries, carrots, turnips, melons, cherry tomatoes, cucumber, lettuce, beets, beans, broccoli, cauliflower and peas.

“Our school garden is pretty much a free-for-all,” Zimba-Kirby said. “Kids can go into it whenever they want and eat whatever they want.”

Zimba-Kirby especially likes the gardening aspect of the FoodCorps program. “We have kids here who are homeless,” she explained. “We have kids here who are on free or reduced lunch, kids who I know don’t get enough to eat and can’t just go to the grocery store and buy whatever they want. So for them to be able to think about growing their own food in the future and having some way to do that can really be an empowering experience – to realize that they can take control of one of their basic needs when they don’t have control over so many things in their lives right now.”

Zimba-Kirby holds monthly taste tests in the cafeteria. This year, she has fed her students parsnip chips, local apples picked by members of the Outsiders Club, and black bean and corn salsa. (The cafeteria has trouble getting the students to eat any beans, she said. She is hoping to help remedy that).

Then there’s that beet salad, which 14-year-old Ben Noyes, who recently discovered he likes kale, gobbled up. Paton would barely even look at the beets, but he threw up a white flag, offering to take a bowl of the salad home to his dad and reassuring Zimba-Kirby that “I normally love the food you do.”

She wasn’t falling for the flattery. She reminded him that he couldn’t possibly know if he likes beets without trying them.

“Dante, I will give a bowl for your dad if you’ll try one little bite from it,” she said. “If you hate it, then you hate it.”

“And if I throw up, it’s your fault,” Paton countered.

He took a microscopic bite.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “That tastes disgusting.”

But he tried it. Small victories.

Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoad

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story