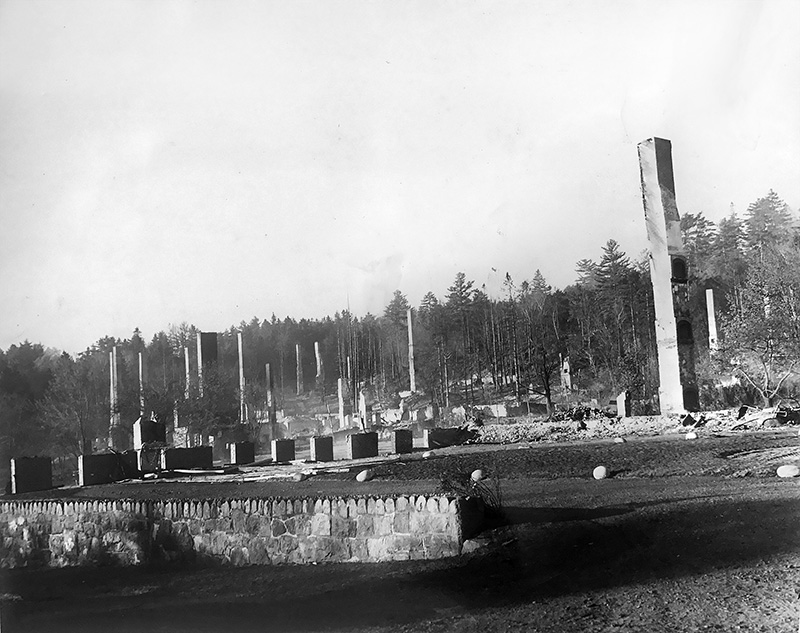

In Bar Harbor, the fires of 1947 burned an estimated 55 percent of the town’s acreage and destroyed more than 200 houses, including many summer “cottages” owned by some of the nation’s wealthiest families.

Yet in many ways, the destruction helped steer Bar Harbor toward the tourist destination that it is today, and it continues to affect the views of visitors to Acadia National Park.

“The year-round residents rebuilt, but few of the summer residents rebuilt their summer cottages or even came back,” Joyce Butler wrote in her book, “Wildfire Loose,” chronicling the 1947 fires and their aftermath. “Millionaires Row along Frenchman Bay is now lined with motels . . . (and) Bar Harbor’s economy, once tied to its cottage owners, now depends on its tourists.”

In total, more than 18,000 acres of Mount Desert Island burned during the forest fires that raged across the state 70 years ago this week.

Roughly 10,000 of those acres were within Acadia National Park, as fires swept across tinder-dry forests and over the tops of Cadillac Mountain, Dorr Mountain and other peaks.

Some of the most dramatic scenes of the 1947 fires, however, played out in the town of Bar Harbor.

Firefighters had been doggedly trying to extinguish small fires for days when, on Tuesday, Oct. 21, high winds took over. By the evening of the 23rd, Bar Harbor residents who hadn’t already fled were evacuated, first to a town athletic field and then toward the town pier at the foot of Main Street.

A crowd of several thousand gathered on the pier in the darkness, trapped between the advancing lines of fire and the angry waters of Frenchman Bay.

With all roads off the island blocked by flames, emergency crews had requested assistance from the Navy, the Coast Guard and eventually from local fishermen to help with a potential water evacuation. But the same gale-force winds that were fanning the flames were whipping up the waves on Frenchman Bay.

The anxious crowd watched flames light up the night sky as the large hotels and homes just on the outskirts of town burned.

“They came and announced we couldn’t stay there, we had to get off the island,” Jane Cormier Obermeyer would tell Butler in a 1980 interview that, like most others she conducted, is preserved in the University of Maine’s special collections. “So, the seas were just unbelievably rough because the wind was wild. And we had two choices: We could go by lobster boats across Frenchman’s Bay or we cold take a chance on the Army trucks going out through the fire zone.”

Obermeyer, her mother and sister would join the vast majority of people who elected to drive out after bulldozers cleared a path on Route 3 through the still-smoldering landscape. Tragically, Obermeyer’s teenaged sister, Helen, would be killed and her mother injured when their Army truck was struck from behind during the evacuation and tipped over. She was one of 16 people who lost their lives during the 1947 fires.

Meanwhile, firefighting crews from throughout Mount Desert Island as well as Ellsworth, Camden, Bucksport, Bangor and other towns had positioned themselves in key locations, hoping to block the fires from destroying the downtown business district. Unlike in the woods of Acadia and in smaller villages, firefighters in Bar Harbor had the benefit of hydrants for their hoses.

Shifting winds played a major part in sparing downtown Bar Harbor. But author Richard Walden Hale Jr., who recounted the scene just two years later in his book “The Story of Bar Harbor,” said much of the credit also goes to the firefighters.

“(Thanks) to the inspiration of Chief Payson of Camden, who sent men forward under wetted-down blankets, it was possible to maintain streams of water at the very point of the fire,” Hale wrote in 1949. “Naturally, it was impossible to save the three great hotels – the de Gregoire at West Street and Eden, the Belmont at Mount Desert and Kebo, and the Malvern on Kebo Street. Once anything caught, it went. But what was wetted down could be saved and by intense effort . . . the fire was held out of town.”

Not only had Bar Harbor’s three largest hotels burned down, but so had 170 year-round homes and 67 summer “cottages” owned by some of the nation’s wealthiest families.

Today, the area of Route 3 just outside of the downtown district, formerly known as “Millionaire’s Row” for its collection of summertime mansions, is occupied by hotels catering to a broader socioeconomic range of visitors.

The fire also changed what visitors see in Acadia National Park, although those views continue to change 70 years later.

William Patterson, professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, has been studying the relationships of forests, fires and humans on Mount Desert Island for more than 30 years.

“Fire, at least during the time since Europeans settled the island in the 1760s, has been a part of the island landscape,” Patterson said.

At the time of the 1947 fire, much of the island was covered with spruce and fir trees, both types of evergreens. After the fires, however, the first species to regenerate in many areas were birch, aspen and other hardwood trees that lose their leaves in the fall.

As a result, Acadia National Park puts on a more spectacular autumnal color display today – displays that draw hordes of leaf peepers annually – than it did before the 1947 fires.

But Patterson said that appears to be changing, once again.

While the 1947 fires killed many spruce and fir trees, seeds of those trees are adapted to survive fire. And over the past 70 years, Patterson said, the evergreens appear to be gradually edging out their deciduous cousins in many areas.

“They are fairly quickly going from aspen and birch to spruce and fir – more quickly than I would have expected,” said Patterson. “With that, the forests will be greener year-round and we won’t have some of the dramatic fall colors.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story