The news, in the spring of 2016, took Hancock County’s worm and clam diggers by surprise.

For the first time since the park opened in 1916, Acadia National Park rangers had begun stopping diggers from working the mud abutting park property. A ranger forced a wormer to dump his catch – a day’s work – in the mud, while clammers had been issued summonses for violating park rules.

“It was kind of a shock to everybody,” recalls local worm digger Jonathan Renwick, secretary of the Independent Maine Marine Worm Harvesters Association. “Everybody here supports the park – it’s a wonderful thing – but we should be able to go to work the way we always have, and hopefully calmer heads will prevail and we’ll be able to.”

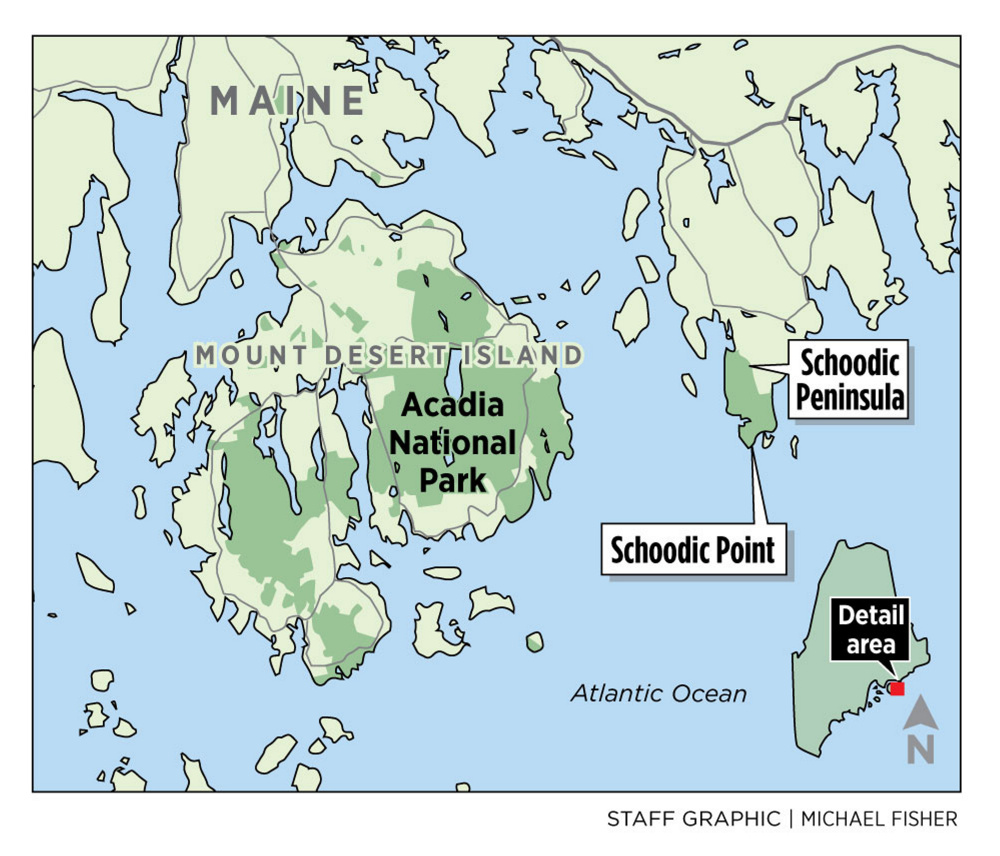

Meanwhile, town officials in the area were already alarmed after learning a universally popular expansion of the park on the Schoodic Peninsula was being accomplished without the approval of Congress, upending the provisions of a 1986 law delineating where the park could and could not expand.

Now the Acadia region awaits a congressional fix to these and other park-related issues that have developed in the 31 years since federal lawmakers last considered property issues in and around New England’s only national park, from rules about how and where the park can expand to whether it should subsidize local trash collection.

Identical bills submitted in the Senate and House in February by Sen. Angus King and Rep. Bruce Poliquin that seek to resolve these issues have been stalled for months on Capitol Hill.

On Sept. 25, Poliquin, a member of the Republican majority, wrote the chairmen of the House Natural Resources Committee imploring them to schedule a hearing as soon as possible. “This comprehensive, common sense bill addresses a number of time sensitive issues,” Poliquin wrote. “Without this legislation moving forward, I fear that the uncertainty for the local communities and for the hardworking shellfish harvesters will create unnecessary stress and conflict within the Bar Harbor Region.”

Poliquin declined to be interviewed, but his spokesman, Brendan Conley, said he had not yet received a response to his letter.

OVERREACHING 1986 BOUNDARY

The bill would make legal the park’s acquisition of the 1,441-acre Schoodic Woods parcel – a coastal woodland with a campground and bike trails anonymously donated in 2015 – while prohibiting it from making any future acquisitions that lie outside a boundary line established by Congress in 1986. It would also direct the park to permit harvesting of marine organisms within the park in accordance with state law and local ordinances and to give a consortium of Mount Desert Island town governments $350,000 to subsidize trash disposal.

Identical bills submitted by Sen. Angus King and Rep. Bruce Poliquin would make legal Acadia National Park’s acquisition of the 1,441-acre Schoodic Woods, which includes a campground, above, and bike trails.

The Department of the Interior, which oversees the National Park Service, and a local board of advisers to the park, the Acadia Advisory Commission, support the bill but are seeking amendments to each of these provisions.

In acquiring Schoodic Woods, federal authorities circumvented a 1986 boundary law that locals thought had represented a binding compromise between Acadia and surrounding municipalities, raising fears that it would set a precedent and allow the park to acquire land wherever it wished.

“In the 1970s, Acadia had no limits on what it could acquire, and it made towns worry about how they could plan for the future – where to put a school or a landfill – when they didn’t know what the park would own in the future,” recalls Ben Emory of Bar Harbor, who sits on the park advisory commission. “There’s no question in the minds of everyone who was here at the time that the intent of the 1986 legislation was to set a permanent boundary, and that anything acquired beyond it would require the approval of Congress.”

To almost everyone’s surprise, in acquiring Schoodic Woods in 2015 – which lies outside the negotiated boundary – Acadia invoked a 1929 law that the 1986 law had presumably replaced, a law that lets the Interior secretary accept donations with little restriction.

The park made the move on the recommendation of its attorneys, in this case the Department of the Interior’s regional solicitor’s office in Newton, Massachusetts. “The question was what legal authorities were available, and the interpretation and advice of the solicitors office was that the 1929 act was a viable authority to receive a donation of land,” park spokesman John Kelly said, noting that Congress had not repealed this older law when it passed the 1986 act.

David MacDonald, president of Friends of Acadia, a nonprofit that advocates for the park, says he thinks it was done without ill intent. “I’m sure they looked at the range of options for accepting Schoodic Woods and probably determined that getting legislation through Congress would be a long road,” he says. “Folks were so excited about the acquisition, people wanted to see the public benefits sooner rather than later.”

“I think it was well-intentioned but underestimated the import people have for the boundary,” he said.

The pending bill would approve the Schoodic Woods expansion but make clear that all further acquisitions must comport to the 1986 law, but the Interior Department and members of the local advisory board say it needs to be amended to allow for minor property adjustments and land swaps to resolve surveying problems that come up from time to time between the park and hundreds of abutting landowners.

“These are needed for the public, not the park,” says Acadia spokeswoman Christie Anastasia. “Someone might have a survey done and discover that a corner of a building they built is on park land. Clearly we don’t want to tell them to take down their building, so we want the ability to do a minor land exchange to clean up the problem. Without that, we’d have to go to Congress to do it.”

Poliquin is opposed to making such a change, spokesman Conley said via email, as he “wants to ensure local residents’ certainty regarding the boundaries of Acadia and not leave them subject to change without going through the proper processes, such as through legislation in Congress.”

Sen. King’s spokesperson said the Senator does not yet have a position on this specific issue. Spokesman Jack Faherty said the senator is working with park officials on park land law “to work out an approach that would make sense for everyone.”

The legislation would also allow marine harvesting in the intertidal zone adjacent to the park as governed by state law, but Maine authorities and the park don’t agree on the issue.

Park authorities have said they regret the enforcement actions taken last year against clammers and wormers, which were decisions made by individual rangers that did not represent an official-mandated change in practice. The park ceased enforcement after harvesters objected, and clammers and wormers have since resumed their work unmolested, pending final resolution by Congress.

Jonathan Renwick of Gouldsboro with a worm he dug in the mud flats on Thompson Island in Acadia National Park. Park authorities have said they regret enforcement taken in 2016 by individual rangers against clammers and wormers, who have since resumed their work. Staff photo by Shawn Patrick Ouellette

REGULATIONS FOR MARINE HARVEST

“We’ve been able to go right on harvesting like we did before,” Renwick says. “The park has acted in good faith with us, and I don’t have any complaints since we mounted our initial resistance. But we would probably complain rather loudly if things don’t go the way they should.”

The details are still up in the air. The Interior Department supports allowing traditional activities such as clamming, worming and periwinkle harvesting to take place using current hand-tool technology but objects to the wording of the bill, which it says would allow mechanical seaweed harvesting, aquaculture operations and other more disruptive activities.

“We have concerns about expanding the harvesting to other ‘marine organisms’ or to aquaculture activity,” acting park service deputy director Robert Vogel said at a July 19 Senate hearing on the bill, arguing that its wording should exclude these activities. “The full range of organisms included in Maine’s definition … could include any species from plants and mollusks to birds, fish and mammals” that live below the high-tide mark.

The Maine Department of Marine Resources says these are not legitimate concerns. Spokesman Jeff Nichols said via email that Maine law does not give his department authority over mammals or birds and clearly stipulates that aquaculture leases can be granted only with the written permission of adjacent coastal landowners – in this case, the National Park Service. Maine courts, Nichols noted, have ruled that rockweed is the property of the neighboring landowner, so it also cannot be harvested without the park’s permission.

“From the state’s perspective, if the NPS’s primary concern is with ensuring the long-term sustainability of marine resources and harvest, the state’s management activities in this regard should be sufficient,” Nichols added.

But others support the park service’s position that nontraditional harvesting be excluded from Acadia’s intertidal areas.

“Friends of Acadia shares the park service’s belief that broadening permitted uses to include seaweed harvests is a concern, and we think legislation should be tweaked to remove such activities that would be of concern,” MacDonald says. “Since none of that is taking place there now, it wouldn’t be taking things away from folks.”

Emory says the park advisory commission – which includes appointees by Gov. Paul LePage as well as the current and previous U.S. Interior secretaries – agrees. “We have a wide range of viewpoints on the commission, but there is unanimity on supporting traditional harvesting and on opposing rockweed or mechanized forms of harvesting,” he said.

Both Poliquin and King are potentially open to adopting more restrictive language on the harvesting issue, their spokesmen said, as the intent is to protect traditional uses.

WASTE DISPOSAL A STICKING POINT

Park advocates are also concerned about a provision in the draft legislation that would require Acadia to provide $350,000 to a coalition of Mount Desert Island towns to subsidize their waste disposal programs.

In the 1986 law, these funds were to support the creation of an island-wide transfer station that the towns have since decided not to build. Park authorities say it is inappropriate to divert the funds to existing trash disposal, especially since the park already pays the towns to dispose of its waste.

MacDonald, of Friends of Acadia, says that if the provision goes through, it would cause significant budgetary problems for the park. “This would have to come out of the park’s existing budget, which is razor thin,” he says. “It would gut visitors’ services, including hiring seasonal assistance, and the downside for surrounding communities would be significant.”

The bills would also let the town of Tremont use a parcel of land – which the park gave it on the condition that it build a now-unwanted school – for other public purposes.

Nobody is certain when the bill might get a hearing in the House, let alone be scheduled for floor votes in both congressional chambers. But park advisory commission chairwoman Jacqueline Johnston of Gouldsboro hopes there’s not a long delay.

“The sooner it’s taken care of, the better the community will feel about it,” Johnston says. “The concept itself is fully supported by the community. It’s just finding the means and methods to get there.”

Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story