The drive between southern Maine and eastern Canada is a long one, and Milton Scott had more questions for his older brother with each passing mile.

It was a few years back, when Barry Scott was still in his 80s. They were driving to visit relatives in Fredericton, New Brunswick, a five-hour trip from their homes in Scarborough and Gorham. Milt knew his brother had joined the Army after high school and fought in World War II. So the conversation, winding with Interstate 95, eventually turned to the war.

Milt was just a toddler when Barry sailed for Italy, and he never knew the details of his brother’s nine months as a German prisoner of war.

“When you sit in a car for 10 hours, five hours up and five hours back, you have a lot to talk about,” said Milt, now 78. “It’s a story that surprised me.”

Milt listened as his brother talked about fighting in the Battle of Anzio, a deadly and drawn-out siege that eventually led to the capture of Rome. He heard about the day Barry was captured by German soldiers in the south of France. He finally learned the meaning of the Bronze Star on the wall.

Barry had kept his stories mostly to himself for nearly seven decades.

“I always thought it was boasting,” said Barry, now 93. “I did not care for boasters or braggarts, period.”

HEAVY LOSSES AT ANZIO

Barry was born in 1924 in New Brunswick.

Shortly after he was born, the family moved to Houlton in northern Maine, where Barry’s three siblings were born. Milt is the youngest.

As Barry came of age, the family moved around New England, and war in Europe began to dominate the headlines. He was a teenager in 1941 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. After his 18th birthday, he received a draft letter. He graduated high school in 1943 and entered the Army at Fort Devens in Massachusetts that summer.

“I think like all young fellows at that age, I anticipated and wanted to do something,” Barry said. “I was drafted, but I would have gone, anyway.”

Barry completed 17 weeks of basic training at Camp Campbell, now called Fort Campbell, in Kentucky. He found it grueling, but his experience on track and cross-country teams in high school helped prepare him.

Once, Barry said a corporal tried to chastise him for a mistake by ordering him to run with his pack and rifle. Five miles later, the corporal was winded and struggling, but Barry was still going strong.

At the end of basic training, the young private shipped overseas. He remembered the vessel with 6,000 troops, the feeling of seasickness, the zigzag travel pattern to avoid a German submarine.

“We were all shipped over as replacements,” Barry said. “They were losing a lot of men.”

The paperwork issued to Barry upon discharge shows he arrived in Northern Africa in March 1944. Within two weeks, he was sent to Italy to join the 180th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Division. Earlier in 1944, that regiment was among British and American troops that landed on Anzio Beach on the west coast of Italy. Their eventual goal was Rome, which was about 30 miles north. Accounts of the campaign show the Germans were largely surprised by the landing, but responded quickly. The Allied forces were soon trapped on the beachhead, surrounded by enemy forces in the hills.

“That was a real bad plan,” Barry quipped. “Not mine, by the way.”

Barry entered a battlefield in stalemate. A Life photographer with the Allied forces in Italy described it as “a slow, maddening, fruitless battle.” An Army history of the 180th Infantry Regiment described that time as “long weary months of incessant shelling and animal-like living.” On May 23, after four months of death and deadlock, the Allied soldiers at Anzio Beach finally broke out of the beachhead. They marched to Rome and took the city by June 4. British and American losses at Anzio Beach totaled 7,000 killed. Another 36,000 were wounded or missing in action. The German troops had 40,000 casualties, including 5,000 dead.

“We saw quite a bit of action, and that’s all I can say on it, really,” Barry said.

His family, however, has coaxed more detail out of him over the years.

He told them about the day he decided to crawl to the neighboring foxhole where his buddy had a coveted Hershey’s bar. Soon after, the foxhole he had just left was hit with a shell, and the men who had been crouched in it with Barry died.

And he told them about the night he took out the Hohner Marine Band harmonica of his boyhood and played the popular love song “Lili Marlene.”

“Somebody from the German side joined in with a harmonica,” Barry said.

PRISONER OF WAR

In August 1944, the 180th Infantry Regiment landed in southern France.

Barry wrote a letter home to his family in Portland a few days later. He asked for news of the outside world and told them about his friend’s 20th birthday. He asked for Necco Wafers and called his youngest brother “Miltie.”

“I wrote a letter to Jim Ott today and made him jealous at how much of the world I am seeing while he is salted away in Louisiana,” Barry wrote. “This is sort of valuable, although I prefer a quiet place in Maine.”

Soon after he arrived in France, however, Barry was driving in a convoy of trucks when they were ambushed by German troops. He estimates only half of the 30 American soldiers in the group survived, and he said he was shot in the left leg during the fighting. Barry and the other survivors were taken prisoner.

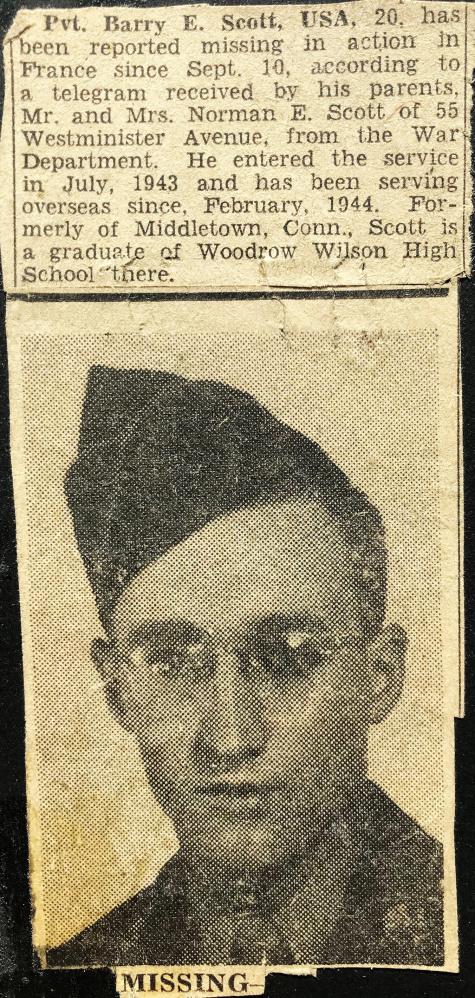

Back home, the Scott family published a notice in the newspaper, saying they received notice Barry had been missing in action since Sept. 10. Barry learned later that his father considered enlisting himself, in a wild attempt to search for his son in Europe. Milt was just a young boy, but he remembered his parents as somber and anxious during that time.

The young American soldiers knew they would be put to work as prisoners of war. They told the Germans they were farmers, hoping to avoid labor in a factory making weapons to be used against their own countrymen. Eventually, Barry was sent to a town called Vilshofen and then a little village called Hilgartsberg. He and 11 other men lived on the upper floor of a former beer hall and worked the plows on local farms. Barry liked the German people he met there. He later told his son Steven about a young boy who was sent to fight with the German army against the Soviet Union at the very end of the war; years later, he still wondered what the boy’s fate had been.

Barry said they received decent treatment as prisoners, although they were forced to sleep naked through the cold winter nights to discourage them from running away. Barry did try to escape once as they marched to another stalag – the German term for a prisoner-of-war camp. He was caught – “quite quickly,” he said with a laugh – and warned he would be shot if he tried again. Barry said he received treatment for blood poisoning from his injury, and the men received boxes of necessities from the American Red Cross.

“In the Red Cross boxes were cigarettes,” Barry said. “I didn’t smoke, but I had a pack. One of the German guards, I said I’d give him three cigarettes if he’d get me a piece of bread. And he did it. How about that?”

Nine months passed like that. But by 1945, the tide of the war was changing. One day in May, Barry said the group of prisoners took over the dwindling group of German soldiers. They knew generally which direction to travel in order to reach the nearest Allied troops, and eventually they found the U.S. 13th Armored Division. Their one-time German captors surrendered, and on June 3, 1945, Barry returned to American soil.

When he got home, Barry said he volunteered to go to the Pacific Theater. But in August, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, ending the war in the Pacific.

THE BRONZE STAR

When World War II ended, Barry went to Bentley University in Boston and became an accountant.

He joined the Maine National Guard, married and had two sons. Mary, his first wife, had two brothers who had served in the military as well. She didn’t like to talk about the war, their son Steven said, which suited Barry just fine. He received a record of his military service and honorable discharge, but he never took much time to review it.

“Making a living became more important than to have something to put on the wall,” Barry said.

He retired on his 80th birthday; his son Steven took over his CPA business in Portland. Barry and his wife had been married 54 years when she passed away. He remarried in 2008, and it was Lorraine who got him talking about his time in the war.

“He said naively one day, ‘During the veterans parades, I see all these soldiers wearing all these ribbons, but I don’t have any,'” said Lorraine, 73. “I said, well, that doesn’t make any sense.”

So she wrote to the Army to inquire about his service record and any medals Barry had been awarded. She got back a Bronze Star, awarded for heroic or meritorious service.

“I was shocked,” Barry said.

Barry and Lorraine also received four medals commemorating his service, including a Prisoner of War medal. They are now proudly framed on the wall in Lorraine’s house. She has also tried to get Barry a Purple Heart, which recognizes service members who have been wounded in action. But by the time Barry was in his 80s, he struggled to find living witnesses to attest to his wound, and their request has been denied three times. Still, Barry doesn’t have much to say when asked about his medals.

“At the time I went in, I wanted to get in that action,” he said. “Most of the guys were like me.”

‘WORLD WAR II VETERAN’

Barry is 15 years older than Milt, and the younger brother tried to emulate the older.

It was peacetime when Milt was graduating from high school, but he also joined the National Guard. He considered a career in business like Barry, although he eventually worked in education instead. Still, the two frequent Harmon’s Lunch for hamburgers and talk every day.

“Scotty idolizes his older brother,” Lorraine said, using a nickname for Milt. “I think his socks were knocked off when he saw all the medals.”

In 2015, Steven and his father went on an Honor Flight to Washington, D.C. Barry, who occasionally uses a cane but mostly walks on his own, was annoyed that he was required to use a wheelchair for travel. But everywhere he goes, Barry wears the “World War II Veteran” hat he got on that trip.

Since that first road trip to Canada, Milt said he and other relatives have encouraged Barry to create a more detailed record of his service. It took some coaxing.

“We tried to get him to write his memoirs,” Steven said. “He would write down a sentence.”

He finally wrote a personal account to be shared with family members. But they continue to ask him questions, and he continues to give them deadpan responses.

“It was quite a time,” Barry said. “I wouldn’t have missed it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.